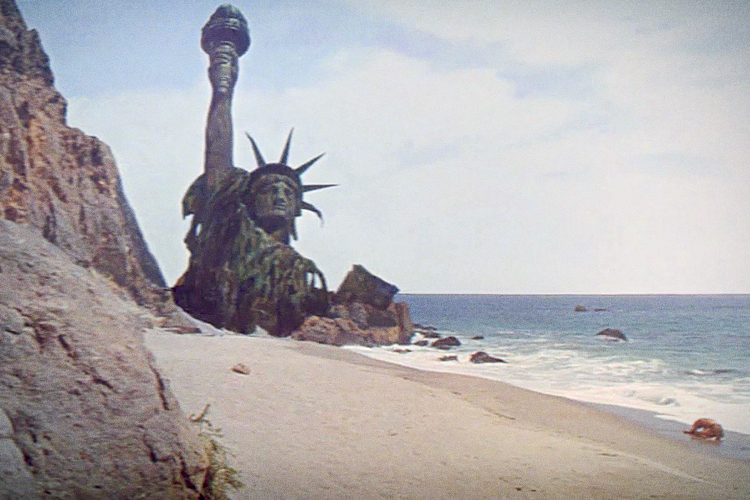

“How can anything survive in a climate like this? A heat wave all year long. A green house effect. Everything is burning up.”

Edward G. Robinson utters the complaint in the opening scene of “Soylent Green,” just before his character, Sol Roth, leaves the tenement he shares with Charlton Heston to pick up his ration of soylent crackers. As he waits in line, food riots erupt. They look a lot like the food riots that exploded around the world the week Heston died in 2008.

Five years later, it wasn’t food riots but a grid-straining heat wave that sent me back to “Soylent Green’s” dystopic New York of 2022. You could hear variations of Roth’s curse on stoops and streets around the city. They were sharpest in the mouths of the old and poor, whom the city encouraged to visit “cooling centers.” In the paranoid frame of mind that follows a sweat-drenched screening “Soylent Green,” the words “cooling center” evoke that movie’s air-conditioned state-run suicide centers. It is to one of these that Sol Roth checks in after learning the secret of the titular food. What he doesn’t know is that the facility provides the “Peo-ple!” of Charlton Heston’s iconic closing cry.

It’s fitting that a “Soylent Green” remake is now in the early stages of development. We have entered an era of deepening heat waves, prolonged droughts, growing interest in insects as a source of protein, and an expanding geriatric population. By imagining the collision of these threads, the cult classic has proved to be something more than just a goofy sci-fi relic about Cheez-It cannibalism. Another major theme, explored in the tender friendship between Heston and Robinson, is the difficulty of being old in a world gone to shit. This theme is most salient for the young audience likely to be targeted by the new “Soylent.” The 1973 original projected 50 years in the future. Projecting 50 from today, there’s no obvious answer to the question: Will today’s 30-year-olds have the option during heat waves of visiting the ultimate “cooling” center? Will there be inducements to make the visit, such as the psychedelic IMAX send-off enjoyed by Sol Roth?

It’s a disturbing question, but not a new one. State-assisted mass suicide has been a recurring motif of postwar science fiction. As the impacts of pollution and resource pressures multiplied, it became easy to imagine a future hostile to the comforts and pleasures of old age as catalogued by the ancients. Among the first to go was Cicero’s favorite, the esteem of the young. The novel upon which “Soylent Green” is based, Harry Harrison’s 1966 “Make Room! Make Room!,” depicts a state of open generational warfare. Its opening pages find a gangland version of the AARP called “the Eldsters” marching in protest from Madison Square Garden to Union Square. Their 65-year-old leader, Kid Reeves, urges militant protest against cuts to their rations of plankton-protein stores. Food riots in the city of 35 million ensue.

Overpopulation didn’t turn out to be the Bomb some predicted in the 1970s. But the steady extension of lifespans has created dilemmas that lurk in the growing national conversation about assisted suicide. Even as our natural environment caves, we continue to make medical advances lengthening human life. At least, it lengthens a version of it. “I’m not afraid of death,” said Woody Allen. “I just don’t want to be there when it happens.” The growing numbers of those suffering the zombie diseases of Alzheimer’s and dementia are granted Allen’s wish. As our bodies are fixed up and kept charging by one intervention after another, often the mind continues to decay. And so we are beginning to ask follow-ups to Roth’s heat wave lament: What is the value of extending life by a series of painful and increasingly witless increments?

And who is going to pick me up and take me to the nearest cooling center?

*

In a May 2012 cover story for New York magazine, Michael Wolff ripped the scab off a soft taboo when he openly wished for the death of his demented mother. “We have created a new biological status held by an ever-growing part of the population,” lamented Wolff, “a no-exit state that [is] nearly as remote from living as from dying.” By 2050, there will be 50 million Americans living in what Wolff calls this “stub period.” The provision of basic, often zoo-like care for these stub souls will cost $1 trillion annually, consuming ever an ever greater share of the federal social budget, more than half of which currently goes to those over 65. Wolff ends the piece by stating his intention to plan and execute a timelier exit. He pleads others to do the same.

There are signs we’re beginning the conversation about death and dying urged upon us by the cultural anthropologist Ernest Becker, whose Pulitzer-winning 1973 work “Denial of Death” laid the groundwork for what’s now known as terror-management theory. Building on Otto Rank and Norman O. Brown’s critiques of Freud, Becker argued that every facet of our civilization and psyches, from religions to neuroses to “Attack of the Killer Tomatoes,” reflects not an obsession with sex, but a universal fear of death. Everything we produce as a culture, in Becker’s theory, is just a gargoyle on a magnificent monument toexistential fear, trembling and nausea. This tabernacle of terror is our distraction and our salve, its erection driven by an otherwise debilitating confusion over the fact that we are born to die.

“The idea of death, the fear of it, haunts the human animal like nothing else,” writes Becker in “The Denial of Death.” “It is the mainspring of human activity — activity designed largely to avoid the fatality of death, to overcome it by denying in some way that it is the final destiny of man.”

Finding a new understanding and relationship with death will require out-thinking the terror-management tactics of the American right. The people who believe most fervently in a Christian afterlife are most hostile to planned exits. They also know that human psychology is on their side. Terror-management studies show that mentions of mortality are active, like LSD and polonium, at micro dosage. An unconsciously registered post-it note of the word “death” placed in the background of one’s visual field can change behavior and effect judgment. This is why the Bush White House upgraded the country’s color-coded terror alert system from “elevated” to “high” on the eve of the 2004 election It’s why GOP operative Betsy McCaughey claimed the Affordable Care Act mandated “end of life” counseling sessions to encourage them to “cut their life short.” In a brilliant terror-management gambit, Sarah Palin called these consultations death panels. On the Ernst Becker subtly spectrum, the phrase approached Lenny Bruce’s “We’re all gonna die!!!” routine during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Amid the death panel freak-out that followed, something important was lost: the Democrats attempted to mollify the Tea Party crowd by stripping Obamacare of a Medicare benefit covering voluntary consultations on end-of-life issues. But the setback can only be temporary. Like gay marriage, end-of-life issues are quickly moving to a new place of public acceptance. This is manifest not just in the euthanasia laws of Oregon and Washington, but in the mainstreaming of hospice, the yogurt of terminal care. Thirty years ago, hospice existed on the fringe of the medical profession. Americans were expected to stay in the hospital until the end, stuck full with tubes. Few people left the hospital or forewent staving interventions to enjoy last moments with family and chirping birds.

At some point, the conversation will expand to include healthy people who do not suffer from terminal illness. Shortly after Wolff’s essay appeared, the New York Times published a symposium on euthanasia laws featuring Philip Nitschke, the Australian right-to-die activist and author of “The Peaceful Pill Handbook.” Nitschke’s book is written for anyone who decides to check out, offering painless homemade remedies with a soft touch, such as helium head-bags and deep sleepy time pill combos. “The Handbook” is an alternative to the rougher routes described in Wataru Tsurumi’s “The Complete Manual of Suicide,” the “Anarchist’s Cookbook” of the genre.

As is so often the case, science fiction anticipated all of this. Indeed, the genre was born with a meditation on the downside of endless dotage by Jonathan Swift.

*

Lemuel Gulliver, the first sci-fi protagonist, rejoices in the third book of his “Travels” upon learning of a race of immortals known as struldbrugs, endemic to the eastern island of Luggnagg. Members are tagged at birth with a red dot over their left eye, which changes to black with deathless age. “Happy nation, where every child hath at least a chance for being immortal!” exclaims Gulliver. “But happiest, beyond all comparison, are those excellent struldbrugs, who, being born exempt from that universal calamity of human nature, have their minds free and disengaged, without the weight and depression of spirits caused by the continual apprehensions of death!”

The Luggnaggians politely disabuse Gulliver of this idea, born out of “the common imbecility of human nature.” They explain that for the thousand or so struldbrugs in the kingdom — roughly twice the growing number of supercentenarians (110 or older) alive today — eternal life does not equal eternal youth and health, but a miserable purgatory. “Envy and impotent desires are their prevailing passions,” explain the Luggnaggians. They envy the young for their vitality, and the mortal old for their ability to die. “Dotage,” or deepening dementia, is the only comfort. By the time the royal court of Luggnagg bids Gulliver goodbye, his “keen appetite for perpetuity of life was much abated.”

Swift’s modern sci-fi descendants would anticipate the intersection of extended life, resource depletion, generational conflict, and runaway climate change. A decade after “Make Room! Make Room!” inspired “Soylent Green” — and Kurt Vonnegut made suicide parlors funny in “Welcome to the Monkeyhouse” — William F. Nolan and George Clayton Johnson depicted a more forceful state solution in “Logan’s Run.” (A remake of the 1977 film is in the works; though Ryan Gosling rescinded his acceptance of the lead in October.) In a domed city of the 23rd century, the palms of newborns are embedded with colored crystals that, like the struldbrugs’s eye dots, change color with time. The final change occurs at age 21, when the crystal turns from red to black. This augers one’s participation in a ceremony known as “Lastday” that takes place in communal suicide centers known as “Sleepshops.” The ritual space is known for its “gaily painted interiors, the attendants in soft pastel robes, the electronically augmented angel choirs, [and] the skin spray of Hallucinogen, which wiped away a look of confused suffering and replaced it with a fixed and joyful smile.”

In the 1976 film version, two traitorous “runners” refuse to participate and flee the dome. They find temporary haven with a semi-mad recluse played by Peter Ustinov. Surrounded by cats, he lives in the ruins of the U.S. Capitol, the last old fart of the human race. Like Michael Wolff’s mother, Ustinov is a little confused.

State-assisted mass suicide would receive its first realistic treatment in British author P.D. James’ 1992 novel “The Children of Men,” which reversed the older narrative of overpopulation. In 2021, a year before the setting of “Soylent Green,” the global sperm bank has been infertile for nearly 20 years. In this ageing, top-heavy society, nature has not been vanquished but is busy reclaiming its supremacy against the dwindling human presence. Like an overpopulated planet, an underpopulated one is a depressing place. Many elderly Britons join a state-run group-suicide ritual known as the Quietus. Participants gather on beaches early in the morning dressed in white night gowns and capes. An unspecified drug is administered and a nearby band plays “cheerful songs… the songs of the Second World War.” The boats take the old out to sea, where they jump in as one with weighted ankles. Those who change their mind at the last minute and cause stress in the others are clubbed to death on the spot.

The 2006 film version of “Children of Men” changed Quietus into an over-the-counter kit with the tagline: “You decide when.” The home-suicide product is packaged like Crest White Strips and advertised on digital billboards that fade into ads for penis pills called Niagra, some kind of benzo-MDMA combo named Bliss, and Big Brother PSA’s urging citizens to report illegal immigrants. Of the many forms of assisted-suicide that populate modern sci-fi, Big Pharma Quietus is the easiest to imagine on future Rite Aid shelves. We can expect the commercials to resemble contemporary ads for Cialis: Couples holding hands in bathtubs on the beach, the sun in the distance rising or setting, depending on your spiritual views. One day these pills will be available through Medicare. But budget-minded death panels won’t push them down anyone’s throat. We will decide when.

*

With its vision of a state administering drugs and managing life-stages like assembly-line products, Aldous Huxley’s “Brave New World” anticipated the books mentioned above. Lesser known is the alternative vision he offered in his last statement, the utopian fantasy Island. Published shortly after Huxley’s death in 1962, the novel described a society that had worked out a relationship between of aging, death and drugs very different from “Brave New World.” Following Huxley’s transformative encounter with mescaline in 1955, he saw hallucinogens as tools for personal and social liberation, not state oppression and mindless escape. On the fictional island of Pala, inhabitants engage in a ritual use of psychedelics that echoes the rite of theEleusinian Mysteries in Ancient Greece. Beginning in adolescence, Palanians periodically consume a hallucinogen called moksha. This includes the onset of terminal illness. The wisdom gained through this use is collected in the island’s unofficial bible, “A Guide to What’s What.”

On his own deathbed, consumed by cancer, Huxley had his wife intravenously administer a high dose of LSD shortly before he passed away on the afternoon of November 22, 1963. Huxley’s use presaged a decade of therapeutic uses for psychedelics to help ease existential anxiety in the terminally ill. This ended with Nixon’s war on drugs and the re-classing of psychedelics to discourage research, but the field is enjoying resurgence in the field of palliative care. The directors of pilot programs at leading medical schools are reporting that psychedelics reduce the paralyzing fear of death. In many cases, it is replaced by acceptance, calm, and an appreciation for the quality of moments rather than their number. As the green parrots have been trained to say on Huxley’s Pala, Here and now, boys. Here and now. Attention…

This is not quite assisted suicide, but those conducting the studies note the ways such acceptance may one day not only usher in an age of “better deaths,” but also relieve the economic pressure of pursuing endless terminal interventions.

“These studies are about more than cancer, they’re about existential questions, and we’re all terminal,” Roland Griffiths of Johns Hopkins told Salon. “You can imagine transforming end of life care, or before, when people are contemplating death. I would predict integrating psychedelics would result in a net huge decrease in expensive interventional procedures. So much money gets poured into those last few months of life where people literally are terrified, grasping at anything to prolong life. It’s heartbreaking to see, but our culture has such a disordered relationship to end of life issues. With a larger perspective, people will change their utilization of the medical system. They’ll use it more in some ways, less in others.”

The generation that appropriated the DuPont slogan “Better living through chemistry” is now completing the circle with “Better deaths through chemistry.”

*

Even if we were heading into a century of climactic and social stability amenable to prolonged, peaceful old age, and even if dementia and Alzheimer’s could somehow be eradicated, there would remain strong arguments for euthanasia laws and using psychedelics to manage our death anxieties. But the new century does not appear like it is planning to be kind to the old. The heat waves that punished Sol Roth are here. They will get worse. The generations in line to inherit the earth will demand options and comfortable, voluntary exits, not just “cooling centers” that may or may not have backup generators. What’s more, they’ll expect a price that keeps them away from the Medicare donut hole. Nine years out from “Soylent Green’s” 2022, the future of assisted suicide is developing into something like a hybrid of Huxley’s psychedelically enlightened Pala, and the consumer “comfort boxes” of “Children of Men.” We have seen some of our parents and grandparents turn into struldbrugs, and we can see the punishing red weather maps ahead. Like wised-up Gullivers, we have no desire to go on, or out, like that.