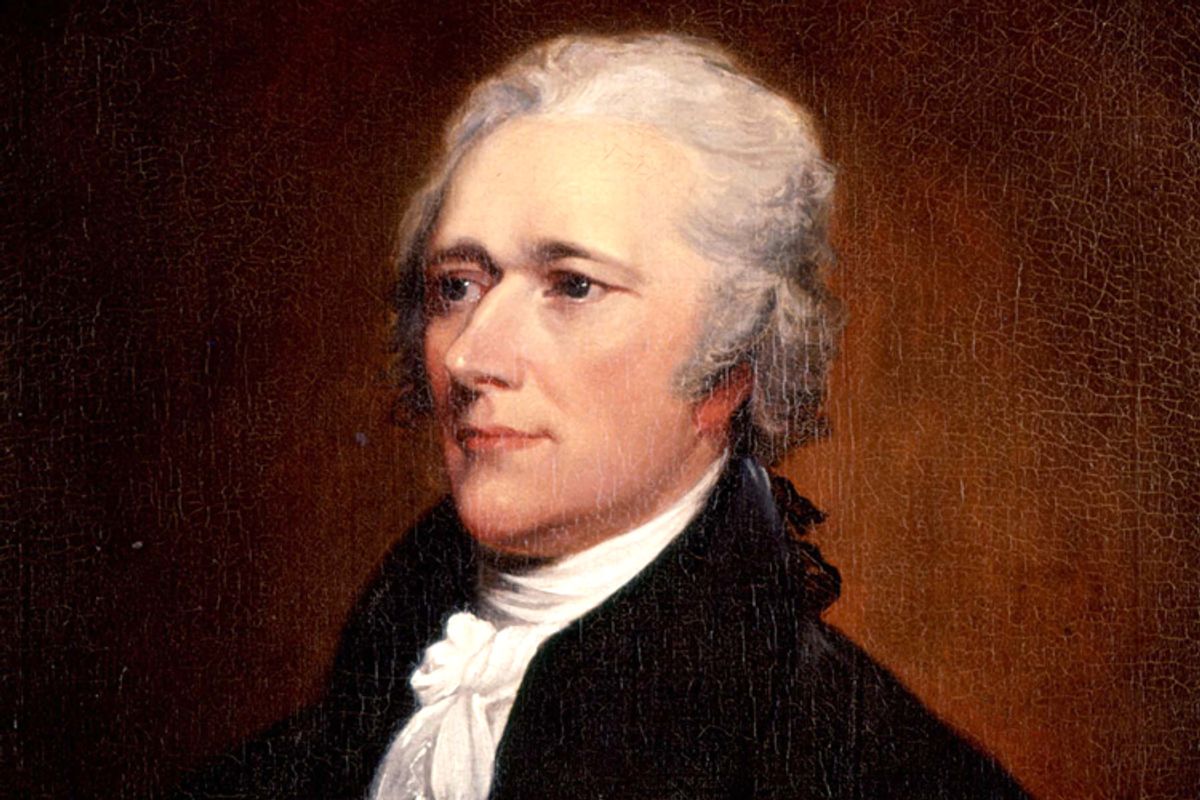

In the summer of 1791, Alexander Hamilton received a visitor.

In the summer of 1791, Alexander Hamilton received a visitor.

Maria Reynolds, a 23-year-old blonde, came to Hamilton’s Philadelphia residence to ask for help. Her husband, James Reynolds, had abandoned her—not that it was a significant loss, for Reynolds had grossly mistreated her before absconding. Hamilton, just 34, was serving as secretary of the United States treasury and was himself a New Yorker; she thought he would surely be able to help her return to that city, where she could resettle among friends and relatives.

Hamilton was eager to be of service, but, he recounted later, it was not possible at the moment of her visit, so he arranged to visit her that evening, money in hand.

When he arrived at the Reynolds home, Maria led him into an upstairs bedroom. A conversation followed, at which point Hamilton felt certain that “other than pecuniary consolation would be acceptable” to Maria Reynolds.

And thus began an affair that would put Alexander Hamilton at the front of a long line of American politicians forced to apologize publicly for their private behavior.

Hamilton (whose wife and children were vacationing with relatives in Albany) and Maria Reynolds saw each other regularly throughout the summer and fall of 1791—until James Reynolds returned to the scene and instantly saw the profit potential in the situation. December 15, Hamilton received an urgent note from his mistress:

I have not tim to tell you the cause of my present troubles only that Mr. has rote you this morning and I know not wether you have got the letter or not and he has swore that If you do not answer It or If he dose not se or hear from you to day he will write Mrs. Hamilton he has just Gone oute and I am a Lone I think you had better come here one moment that you May know the Cause then you will the better know how to act Oh my God I feel more for you than myself and wish I had never been born to give you so mutch unhappiness do not rite to him no not a Line but come here soon do not send or leave any thing in his power.

Two days later, Hamilton received a letter from James Reynolds that accused him of destroying a happy home and proposed a solution:

Its true its in your power to do a great deal for me, but its out of your power to do any thing that will Restore to me my Happiness again for if you should give me all you possess would not do it. god knowes I love the woman and wish every blessing may attend her, you have bin the Cause of Winning her love, and I Dont think I Can be Reconciled to live with Her, when I know I hant her love. now Sir I have Considered on the matter Serously. I have this preposial to make to you. give me the Sum Of thousand dollars and I will leve the town and take my daughter with me and go where my Friend Shant here from me and leve her to Yourself to do for her as you thing proper. I hope you wont think my request is in a view of making Me Satisfaction for the injury done me. for there is nothing that you Can do will compensate for it.

Rather than leave town (and his new mark), James Reynolds allowed the relationship to continue. A pattern was established in which Maria Reynolds (by this time likely complicit in her husband’s scheme) would write to Hamilton, entreating him to visit when her husband was out of the house:

I have kept my bed those tow days past but find my self mutch better at presant though yet full distreesed and shall till I se you fretting was the Cause of my Illness I thought you had been told to stay away from our house and yesterday with tears I my Eyes I beged Mr. once more to permit your visits and he told upon his honnour that he had not said anything to you and that It was your own fault believe me I scarce knew how to beleeve my senses and if my seturation was insupportable before I heard this It was now more so fear prevents my saing more only that I shal be miserable till I se you and if my dear freend has the Least Esteeme for the unhappy Maria whos greateest fault Is Loveing him he will come as soon as he shall get this and till that time My breast will be the seate of pain and woe

P. S. If you cannot come this Evening to stay just come only for one moment as I shal be Lone Mr. is going to sup with a friend from New York.

After such trysts occurred, James Reynolds would dispatch a request for funds—rather than demand sums comparable to his initial request of $1,000 dollars (which Hamilton paid), he would request $30 or $40, never explicitly mentioning Hamilton’s relationship with Maria but referring often to Hamilton’s promise to be a friend to him.

James Reynolds, who had become increasingly involved in a dubious plan to purchase on the cheap the pension and back-pay claims of Revolutionary War soldiers, found himself on the wrong side of the law in November 1792, and was imprisoned for committing forgery. Naturally, he called upon his old friend Hamilton, but the latter refused to help. Reynolds, enraged, got word to Hamilton’s Republican rivals that he had information of a sort that could bring down the Federalist hero.

James Monroe, accompanied by fellow Congressmen Frederick Muhlenberg and Abraham Venable, visited Reynolds in jail and his wife at their home and heard the tale of Alexander Hamilton, seducer and homewrecker, a cad who had practically ordered Reynolds to share his wife’s favors. What’s more, Reynolds claimed, the speculation scheme in which he’d been implicated also involved the treasury secretary. (Omitted were Reynolds’ regular requests for money from Hamilton.)

Political enemy he might have been, but Hamilton was still a respected government official, and so Monroe and Muhlenberg, in December 1792, approached him with the Reynolds’ story, bearing letters Maria Reynolds claimed he had sent her.

Aware of what being implicated in a nefarious financial plot could do to his career (and the fledgling nation’s economy), Hamilton admitted that he’d had an affair with Maria Reynolds, and that he’d been a fool to allow it (and the extortion) to continue. Satisfied that Hamilton was innocent of any wrongdoing beyond adultery, Monroe and Muhlenberg agreed to keep what they’d learned private. And that, Hamilton thought, was that.

James Monroe had a secret of his own, though.

While he kept Hamilton’s affair from the public, he did make a copy of the letters Maria Reynolds had given him and sent them to Thomas Jefferson, Hamilton’s chief adversary and a man whose own sexual conduct was hardly above reproach. The Republican clerk of the House of Representatives, John Beckley, may also have surreptitiously copied them.

In a 1796 essay, Hamilton (who had ceded his secretaryship of the treasury to Oliver Wolcott in 1795 and was acting as an adviser to Federalist politicians) impugned Jefferson’s private life, writing that the Virginian’s “simplicity and humility afford but a flimsy veil to the internal evidences of aristocratic splendor, sensuality, and epicureanism.” He would get his comeuppance in June 1797, when James Callender’s The History of the United States for 1796 was published.

Callender, a Republican and a proto-muckraker, had become privy to the contents of Hamilton’s letters to Reynolds (Hamilton would blame Monroe and Jefferson, though it is more likely Beckley was the source, though he had left his clerk’s position). Callender’s pamphlet alleged that Hamilton had been guilty of involvement in the speculation scheme and was more licentious than any moral person could imagine. “In the secretary’s bucket of chastity,” Callender asserted, “a drop more or less was not to be perceived.”

Callender’s accusations and his access to materials related to the affair left Hamilton in a tight spot—to deny all the charges would be an easily proven falsehood. The affair with Maria Reynolds could destroy his marriage, not to mention his hard-won social standing (he had married Elizabeth Schuyler, daughter of one of New York’s most prominent families, and a match many thought advantageous to Hamilton). But to be implicated in a financial scandal was, to Hamilton, simply unthinkable. As Secretary of the Treasury, he’d been the architect of early American fiscal policy. To be branded as corrupt would not only end his career, but also threaten the future of the Federalist Party.

Left with few other options, Hamilton decided to confess to his indiscretions with Maria Reynolds and use that confession as proof that on all other fronts, he had nothing to hide. But his admission of guilt would be far more revealing than anyone could have guessed.

Hamilton’s pamphlet Observations on Certain Documents had a simple purpose: in telling his side of the story and offering letters from James and Maria Reynolds for public review, he would argue that he had been the victim of an elaborate scam, and that his only real crime had been an “irregular and indelicate amour.” To do this, Hamilton started from the beginning, recounting his original meeting with Maria Reynolds and the trysts that followed. The pamphlet included revelations sure to humiliate Elizabeth Hamilton—that he and Maria had brought their affair into the Hamilton family home, and that Hamilton had encouraged his wife to remain in Albany so that he could see Maria without explanation.

Letters from Maria to Hamilton were breathless and full of errors (“I once take up the pen to solicit The favor of seing again oh Col hamilton what have I done that you should thus Neglect me”). How would Elizabeth Hamilton react to being betrayed by her husband with such a woman?

Still, Hamilton pressed on in his pamphlet, presenting a series of letters from both Reynoldses that made Hamilton, renowned for his cleverness, seem positively simple. On May 2, 1792, James Reynolds forbade Hamilton from seeing Maria ever again; on June 2, Maria wrote to beg Hamilton to return to her; a week after that, James Reynolds asked to borrow $300, more than double the amount he usually asked for. (Hamilton obliged.)

Hamilton, for his part, threw himself at the mercy of the reading public:

This confession is not made without a blush. I cannot be the apologist of any vice because the ardor of passion may have made it mine. I can never cease to condemn myself for the pang which it may inflict in a bosom eminently entitled to all my gratitude, fidelity, and love. But that bosom will approve, that, even at so great an expense, I should effectually wipe away a more serious stain from a name which it cherishes with no less elevation than tenderness. The public, too, will, I trust, excuse the confession. The necessity of it to my defence against a more heinous charge could alone have extorted from me so painful an indecorum.

While the airing of his dirty laundry was surely humiliating to Hamilton (and his wife, whom the Aurora, a Republican newspaper, asserted must have been just as wicked to have such a husband), it worked—the blackmail letters from Reynolds dispelled any suggestion of Hamilton’s involvement in the speculation scheme.

Still, Hamilton’s reputation was in tatters. Talk of further political office effectively ceased. He blamed Monroe, whom he halfheartedly tried to bait into challenging him to a duel. (Monroe refused.) This grudge would be carried by Elizabeth Hamilton, who, upon meeting Monroe before his death in 1825, treated him coolly on her late husband’s behalf. She had, by all accounts, forgiven her husband, and would spend the next fifty years trying to undo the damage of Hamilton’s last decade of life.

Hamilton’s fate, of course, is well-known, though in a way the Reynolds affair followed him to his last day. Some time before the publication of his pamphlet, Hamilton’s former mistress Maria Reynolds sued her husband for divorce. The attorney that guided her through that process was Aaron Burr.

Shares