When the ambulance crew arrived, about 8:20 p.m., Joan Boice was in the TV lounge, face-down on the carpet. Her head had struck the floor with some velocity; bruises were forming on her forehead and both cheeks. It appeared she’d lost her balance and fallen out of a chair.

When the ambulance crew arrived, about 8:20 p.m., Joan Boice was in the TV lounge, face-down on the carpet. Her head had struck the floor with some velocity; bruises were forming on her forehead and both cheeks. It appeared she’d lost her balance and fallen out of a chair.

But no one at the assisted living facility could say precisely how the accident had occurred. No one knew how long Joan had been splayed out on the floor. She had defecated and urinated on herself.

Worried that Joan might have injured her spine, the emergency medical personnel gently rolled her over and placed her on a back board. They pumped oxygen into her nostrils.

It was Sept. 22, 2008 — just 10 days after Joan had first moved into Emerald Hills.

No Emeritus employees accompanied Joan to the hospital. And even though Joan’s husband, Myron, was living in the facility, the Emeritus workers didn’t immediately alert him that Joan had fallen and hurt herself. Joan, confused, injured, and nearly mute, ended up in the local hospital by herself, surrounded by strangers.

It was supposed to have been a festive night for Joan’s son Eric and his wife, Kathleen, who lived nearby. They were throwing a birthday party for their daughter, then in elementary school. The celebration was interrupted when a doctor called from the hospital with news of Joan’s fall. As Kathleen recalled it, the physician was somewhat baffled — he didn’t understand what Joan was doing in the emergency room without a family member, and he was having trouble deducing the extent of her injuries because she couldn’t communicate.

California law requires assisted living companies to conduct a “pre-admission appraisal” of prospective residents, to ensure they are appropriate candidates for assisted living.

But Emerald Hills took Joan in without performing an appraisal. It wasn’t for lack of time. The Boices had signed the contract to live at Emerald Hills more than two weeks before Joan moved in.

Joan, then, had taken up residence in the memory care unit at Emerald Hills. The unit — referred to as a “neighborhood” by the company — is a collection of about a dozen small apartments on either side of a central hallway. At each end of the hallway are heavy doors equipped with alarms, which sound when anyone enters or leaves. The alarm system is meant to prevent residents from simply walking off.

On the day Joan moved into Room 101 in the unit, a company nurse named Margaret “Peggy” Stevenson briefly looked her over. The nurse realized that Joan needed to be monitored closely to keep her from falling — she wrote it down in her cursory assessment — but facility records show she didn’t craft any kind of detailed plan for her care and supervision.

Stevenson, asked years later about Joan, said she could recall nothing about her or her stay at Emerald Hills.

Kathleen had immediate suspicions about Joan’s fall. The family, she said, had warned the facility not to leave Joan sitting in a chair without supervision because she was liable to try to stand up, lose her balance, and topple to the floor. Joan had fallen several times during an earlier stay in an assisted living facility near Sacramento, but the staff had developed a specific plan to address the issue.

Despite the warning, Kathleen said that when she visited Emerald Hills during Joan’s first days there she often found her mother-in-law sitting in a chair alone.

The recent track record at Emerald Hills featured a host of falls similar to Joan’s, and ambulances were often called to take the injured off to the hospital. Falls are a particular hazard for the elderly, and assisted living facilities like Emerald Hills are required to report them to state regulators.

Internal company records documented 112 falls at Emerald Hills in 2008. Some residents fell repeatedly.

Consider the case of one Emerald Hills resident, 83-year-old Dorothy “Dottie” Bullock.

On April 5, 2008, an Emeritus employee discovered Bullock “on the floor in a semi-seated position” in the memory care unit, according to a state report. She “was unable to tell” the worker what had happened to her. The incident was described as a fall in state records. Emerald Hills sent her to the hospital.

On April 7, Bullock, back at Emerald Hills, fell again, according to the handwritten log of her personal attendant, who was hired by Bullock’s husband to give her extra help.

On April 8, Bullock, complaining of pain, was hauled by ambulance back to the hospital. Doctors concluded that she’d fractured her pelvis, but soon returned her to Emerald Hills. She fell again on April 12.

Bullock would fall again months later, for the final time.

Emeritus records show Bullock tumbled in front of her apartment and was found on the carpet with her aluminum walker beneath her. Blood spilled from her nose and a “bump” developed on her forehead, according to the company documents. The impact broke a vertebra in Bullock’s neck and crushed her nasal bones and sinus structures, hospital records show. A CT scan revealed possible fractures of both eye-sockets and the base of the skull.

Dottie Bullock died in the emergency room.

While Emeritus recorded the fatality in its internal logs, the company did not report her death to state regulators, a violation of California law. The state requires assisted living facilities to file reports on all deaths, even those believed to be from natural causes, so that it can look into suspicious or troubling incidents.

Emeritus said it lacked information about Bullock’s death and thus could not say why it had occurred.

Bullock’s personal attendant, Julie Covich, says Bullock was not supervised properly.

“I think there was neglect,” said Covich, who usually visited Emerald Hills once or twice a week to help out Bullock. “I would go in there and never see a caregiver.”

“It was hard to find anyone that was running the place,” she said. “It was crazy.”

“Heads on the Beds”

In early 2008, the year Joan Boice entered Emerald Hills, Emeritus rolled out a new business campaign. The company dubbed it the “No Barriers to Sales” effort.

The concept was straightforward: Move as many people as possible into Emeritus facilities. Wall Street was looking closely at the company’s quarterly occupancy numbers and a few percentage points could propel the stock price upward or send it tumbling down.

With the housing market foundering, Emeritus needed to step up its sales efforts.

In case there was any confusion about just how seriously the company took this new campaign, a company vice president sent a blast email to facility directors across California. In the body of the email, the vice president got right to it:“SALES and your commitment to sales is your highest priority right now.” Facility directors, the message concluded, would be “held responsible for census and occupancy growth.”

Emeritus employees across the country realized they were entering a new era.

“There was a different sense of urgency. The tone was different,” said a former Emeritus manager who ran a facility at the time. “The message from above was put as many people as possible in the beds and make as much money as possible. That’s what they said. Verbatim. Honestly.”

According to Lisa Paglia, a regional executive in California at the time, Budgie Amparo, the company’s top official for quality control, was openly critical when a Northern California facility declined to admit someone who did not have a doctor’s evaluation.

Such evaluations, which are designed to keep out seniors with problems that assisted living facilities aren’t equipped to handle, are required under a California law known as Title 22.

But on a conference call with roughly half a dozen California managers, Paglia said, Amparo declared that the Northern California facility should have admitted the resident.

“Our priority,” Amparo declared, according to Paglia, “is to get the heads on the beds.”

The issue arose again in October 2008 during a training session for approximately 25 facility directors and salespeople held at an Emeritus property in Tracy, Calif. During the seminar, a company vice president reiterated Amparo’s instruction to disregard California law, according to court records and interviews.

The mandate prompted something of a staff revolt.

At least one facility director spoke out at the meeting: His license to operate the facility was at stake, he said.

An employee who worked at the Tracy facility eventually alerted California regulators. The state dispatched an investigator, and state records show that the investigator met with employees who confirmed that a company official had approved the practice of admitting someone without a doctor’s report. The investigator reviewed a random sample of seven resident files, finding that two people had been moved in illegally, documents show.

Amparo, a nurse whose full title is executive vice president of quality and risk management, denies directing employees to violate the regulation. In a written statement, Emeritus said, “Neither Budgie Amparo nor any of our other officers issued a directive to violate Title 22 or any other law. Emeritus does not condone allowing residents to move in without the proper documents.”

Emeritus eventually fired Paglia, and lawyers for the company have since portrayed her as a poor worker who failed to do her job competently. Along with two other former Emeritus employees, Paglia sued the company alleging wrongful termination, and wound up settling on secret terms.

For assisted living chains such as Emeritus, there is a powerful business incentive to boost occupancy rates and to take in sicker residents, who can be charged more.

Emeritus, for its part, rejects any suggestion that a quest for profits has tainted its admission practices. But in interviews, former Emeritus executives described a corporate culture that often emphasized cash flow above all else. The accounts of the executives, who spoke independently but anonymously, were strikingly consistent.

“It was completely focused on numbers and not human lives,” said one executive, who worked for Emeritus for more than three years and oversaw dozens of facilities in Eastern states.

The company’s emphasis on sales and occupancy rates, the executive said, transformed the workforce into “a group of people who were grasping at every single lever they could pull to drive profitability.”

Emeritus operates a sophisticated, data-driven sales machine. There are occupancy goals for each facility, as well as yearly company-wide goals. The company tracks dozens of data points — including every move-in and move-out of residents — in a vast database. It posts a monthly snapshot of each facility’s sales statistics on an internal website, allowing employees to see which strategies are most successful.

Sales specialists are instructed on how to use psychology to persuade potential customers to sign on. One suggestion: Give the customer “a sense of control and choice by offering two possible options.” A 2009 Emeritus sales manual, which runs 181 pages, encourages sales people to generate publicity by hosting seminars on Alzheimer’s or organizing charity efforts in the event of a natural disaster like a “flood or earthquake.”

Emeritus motivates its workforce with a broad range of financial incentives. There are bonuses for hitting monthly occupancy goals. Bonuses for hitting yearly occupancy goals. Bonuses for boosting overall earnings. And the money doesn’t just go to sales people: The company hands out checks to maintenance workers, nurses, facility directors and other workers.

Nurses play a key role in assisted living, providing much of the hands-on care. But nurses at Emeritus facilities are also expected to be deeply involved in increasing revenue by making sales.

During more than a year of reporting, ProPublica and PBS Frontline spoke to 10 facility directors who said nurses were required to participate in weekly conference calls focusing on little but economics. Those accounts are backed by an internal Emeritus document that lays out the agenda for the weekly calls and that shows an overarching concentration on finances.

Doris Marshall was at the forefront of Emeritus’s efforts to have nurses play the dual roles of caregivers and salespeople. After receiving her nursing license in 1984, Marshall had spent many years tending to patients in the emergency department of a Southern California hospital, and she’d later gone on to help run a nursing school.

Marshall was to oversee the well-being of roughly 800 elderly people. But her job description went well beyond that: She was to help with “marketing” and “attaining financial goals.” Her job, in the end, actually involved very little nursing.

Instead, she said, she was drawn into Emeritus’s evolving strategies aimed at upping its revenues. The company planned to bring in more seniors with Alzheimer’s and dementia because they could be charged more, she said. Her boss gave her a digital tracking tool showing how much more money Emeritus could make by admitting sicker, frailer residents.

By the fall of 2010 Marshall was worn out and disillusioned. She quit.

Emeritus’s extraordinary drive to put heads in beds — perhaps routine in, say, the hotel industry — has distorted the admissions process at some facilities, records and interviews show. Since 2007, state investigators have cited the company’s facilities more than 30 timesfor housing people who should have been prohibited from dwelling in assisted living facilities.

A 2010 episode at an Emeritus facility in Napa highlighted the perils of improperly admitting people. The facility rented a room to a 57-year-old woman with an eating disorder, depression, bipolar disorder and a history of suicide attempts. The woman, who was distraught over the death of her husband, taped a note to her door saying she wasn’t to be disturbed and committed suicide, overdosing on an amalgam of prescription painkillers.

The state’s investigation into the death was scathing: the woman should never have been allowed to move in; the staff had missed or ignored bulimic episodes and her obvious weight loss; no plan of care was ever developed or implemented despite the resident’s profound psychological problems.

Emeritus, asked to respond to the state’s investigation, said only that the woman had overdosed on drugs she had brought into the facility on her own, and that as a result they could not be faulted in her death.

“She Barely Even Talked to Us”

In the aftermath of her fall in September 2008, Joan returned to Emerald Hills. But the staff, inexperienced and often exhausted, worried about her.

“She couldn’t walk, she couldn’t feed herself, she barely even talked to us, and her health wasn’t that good,” recalled Jenny Hitt, a former medication technician at Emerald Hills.

But if concern was abundant at Emerald Hills, expertise was in short supply.

Alicia Parga ran Joan’s memory care unit. On some weekends, she managed the entire building — not only the wing of residents with dementia, but the rest of the three-story assisted living facility, one that could hold a total of more than 100 residents.

After Parga started on the job, it took Emeritus roughly 18 months to give her any training on Alzheimer’s and dementia. The state regulations were hardly substantial: Someone such as Parga was obligated to get six hours of training during her first four weeks on the job. But even that requirement wasn’t met.

Emeritus has insisted that Emerald Hills had properly trained personnel to care for Joan and others, and they described Parga as a woman deeply invested in tending to the residents.

But Parga, who had barely earned a high school degree, wasn’t even familiar with the seven stages of dementia. Though she was responsible for the well-being of 15 or more seriously impaired people, as well as the supervision of employees, Parga was paid less than $30,000 per year.

Catherine Hawes, a health care researcher at Texas A&M University, conducted the first national study of assisted living facilities. In her view, training is absolutely crucial. A well-educated employee can “interpret non-verbal cues” from people like Joan, intercept seniors before they wander away from the building, or keep residents from eating or drinking poisonous substances.

“You can do great care,” she said. “You just — you’ve got to know how.”

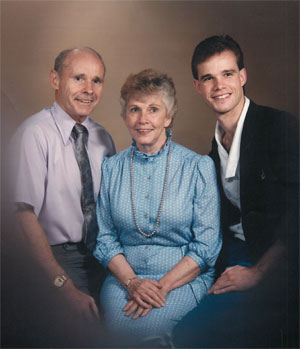

Other than the Emeritus employees working in the memory care unit at Emerald Hills, only one person saw Joan enough to know what kind of daily care she was getting: Her husband, Myron.

He was worried. And he did his best to sum up his concerns to his son Eric:

“They’re not treating Mom well.”

Shares