BRUSSELS, Belgium — Call it ironic. For a short time at least, growing fish stocks in European waters can be counted among the rare positive side effects of climate change, especially for the Icelandic fishermen who first discovered a few mackerel flapping around their nets back in 2006.

BRUSSELS, Belgium — Call it ironic. For a short time at least, growing fish stocks in European waters can be counted among the rare positive side effects of climate change, especially for the Icelandic fishermen who first discovered a few mackerel flapping around their nets back in 2006.

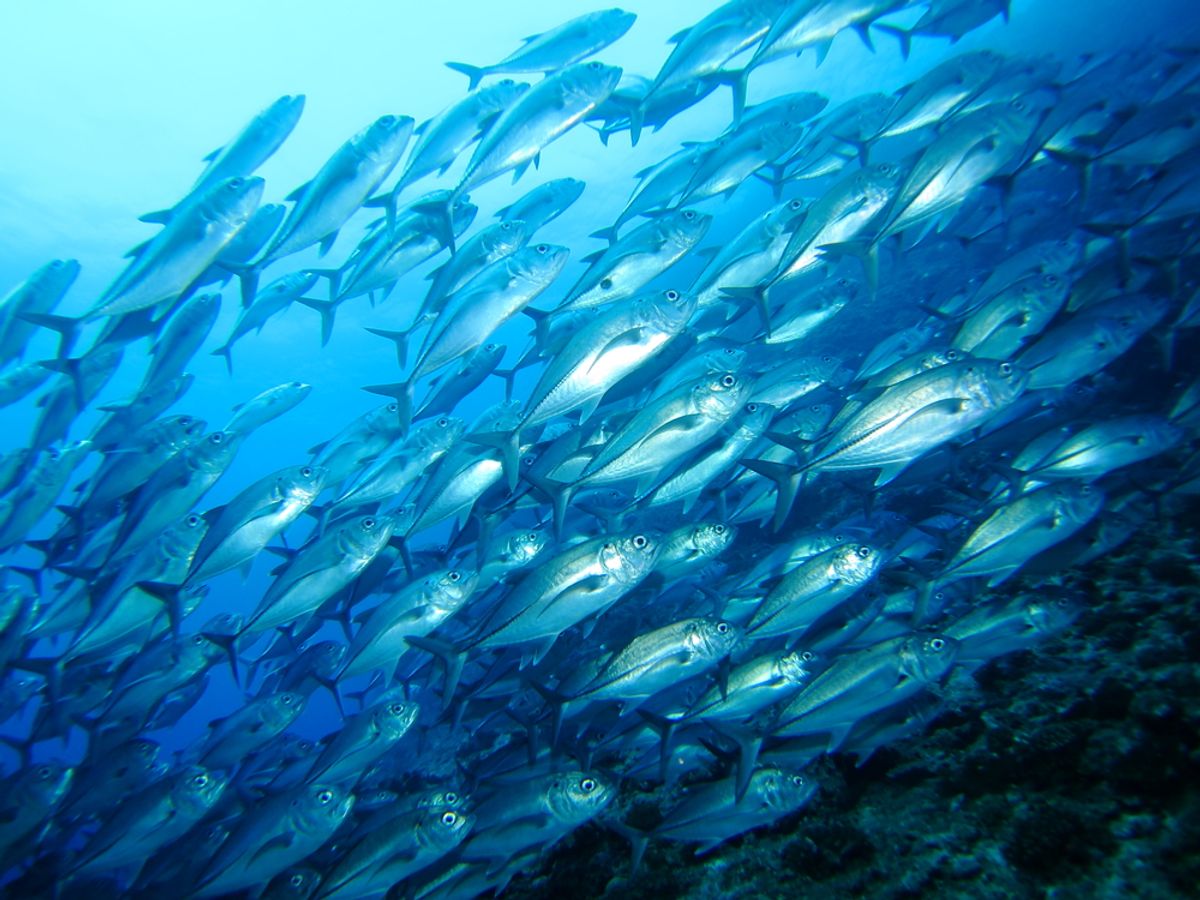

They hadn’t come across the species for decades, and the migrating shoals lured north by the rise in sea temperatures couldn’t have come at a better time. The burgeoning riches at sea coincided with economic disaster on land: Iceland's government encouraged its citizens to go out and fish to help revive the nation after its 2008 banking crisis.

But it wasn’t long before squabbling began over who has the right to cash in on the newfound bounty. A year after its banks collapsed, Iceland declared it would stop observing mackerel quotas agreed with the European Union, Norway and the Faroe Islands — a small archipelago north of Scotland and under the protection of Denmark.

It set own catch limit instead to reflect the shifting patterns of migration, sparking a dispute reminiscent of the Cod Wars of the 1960s and 1970s, when British and Icelandic vessels waged battles at sea over their competing claims.

Although the new round — dubbed the “mackerel wars” — hasn’t seen any actual shots fired so far, the EU this week is expected to trigger its most powerful economic salvo yet by launching the procedure for enacting sanctions against Iceland that could eventually ban its catches from EU ports.

EU officials are also expected to formally approve similar sanctions against the Faroe Islands over herring catches — measures EU officials say are necessary to prevent overfishing and protect future fish stocks.

Observers say the main problem the EU faces is obvious: Fish go where they find the best feeding and spawning grounds, oblivious to the political rows they create in their wake.

“The fact that these fish aren't necessarily carrying a passport and flying a flag for a particular nation means that it starts to get interesting when they start to move out of EU jurisdiction,” marine biologist Stephen Simpson of the University of Exeter said in an interview.

EU member states will vote on sanctions against the Faroe Islands on Wednesday. With Britain, Ireland, Spain, France and Portugal all supporting the move, the measures are likely to pass with the majority needed to start applying them within weeks.

A formal decision over pursuing similar measures against Iceland is expected by the end of the month.

If they pass, the two cases will mark the first time the EU will have used a new trade sanctions tool introduced to tackle the mackerel wars, which erupted in 2009 when Iceland — which is not a member of the EU — first unilaterally set its mackerel quota at more than 123,000 tons.

The EU fisheries chief, Maria Damanaki, has said the bloc “cannot permit unilateral actions that can destroy the stocks.”

Iceland and the Faroe Islands argue that the rise in sea temperatures caused by a combination of global warming and natural factors has sent such large quantities of mackerel and herring further north that the allocations should have been amended to reflect that.

Iceland's catch has risen from practically nothing in 2006 to a peak of more than 170,000 tons in 2011. Sigurgeir Thorgeirsson, Iceland's chief fisheries negotiator, says his government is prepared to lower its quota, but only after fair negotiation with the other countries fighting for a share of the bounty.

“It has been estimated that over the last three years, nearly 30 percent of the mackerel stock in the Northeast Atlantic spends the summer for feeding in Icelandic waters, eating up to nearly three million tons of food in the sea, in direct competition with other fish stocks and really having a great impact on the ecosystem,” he says.

The Faroe Islands unilaterally set its herring quota at 115,000 tons for the first time this year, citing the refusal of the other fishing nations to renegotiate their current allocation of five percent of the total catch.

Kate Sanderson, the Faroe Islands head of mission in Brussels, says she’s “pessimistic” about the outcome of Wednesday's vote. If it goes against them, the Faroese government will look at legal measures to challenge the decision.

The mackerel wars could be the first of many battles over rights to the shifting fish stocks. Simpson says a study a few years ago found that three-quarters of demersal fish — those living and feeding at the bottom of the sea — were also responding to the warming oceans.

“Normally when you read a climate change story, it's bad news when we talk about the environment, but what we're seeing that many more species were increasing due to warming than declining,” he explains.

They are now looking at the response of pelagic fish such as mackerel and herring, which live near the surface. Simpson says initial analysis shows “the response of pelagic is even more rapid then the response of domersal fish.”

Warming oceans aren’t good news for everyone, however. A study published in the journal Nature found that stocks could decrease in warmer equatorial waters, with potentially devastating economic consequences in developing countries there.

For Europe, however, with ocean temperatures set to continue rising, fisheries could be looking at a sustained if temporary fishing boom that, according to Simpson, will make it imperative to “nail the politics of fish crossing borders.”

Shares