As a child in Southern California, I was scared of hippies, and not just because they looked weird, listened to creepy music and were reputed to flip out regularly on drugs -- though those things certainly didn't help. The fear that I (and most of my little friends) felt toward hippies derived from a single, two-word taproot: Manson Family. In the late '60s and early '70s all the anxiety surrounding the counterculture seemed to crystalize in this freaky, zombified, nihilistic band of spree murderers and their wild-eyed guru, Charles Manson, complete with that X he cut into the flesh between his own eyes. They arrived in the news just when my friends and I reached the prime age for trafficking in sensationalistic playground legends, and we made the most of them.

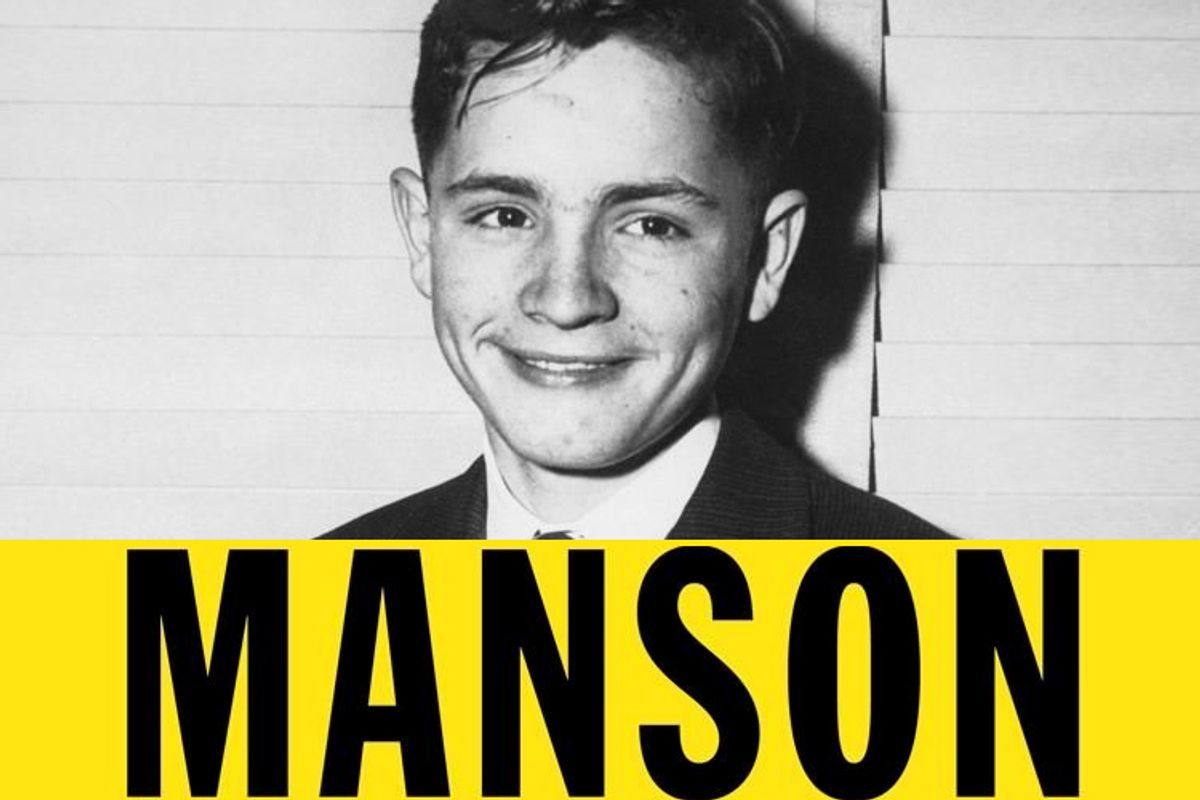

Not that the adults around us responded with much more sobriety. There have been many books about Charles Manson and his followers, and quite a few of them read like they could have been dictated by a precocious 8-year-old regaling the crowd hanging out by the drinking fountain: "I heard they were Satanissssts!" Jeff Guinn's "Manson: The Life and Times of Charles Manson" is not that kind of book. Here's how Guinn describes Southern California's infamous Santa Ana winds, which have pulled dark poetry from the pens of Raymond Chandler and Joan Didion: "hot gusts frequently topping a hundred miles per hour that annually plagued Los Angeles and the surrounding area from late fall through early spring, drying out the land and paving the way for periodic brush fires that destroyed substantial sections of the region."

So, yeah, prosaic, but this is one story that could use a little less florid coloring and a lot more shoe-leather reporting. Guinn secured prison interviews with two Family members, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten, both of whom were convicted of participating in the cult's most notorious crimes, the Tate-LaBianca murders of August 1969. He also spoke in depth with Manson's cousin and his adoptive sister, sources who endow "Manson" with the richest and most revealing portrait yet of Manson's early life.

Manson himself refused to grant Guinn an interview, but the impression left by this biography is that it was hardly necessary. The Manson Guinn portrays is not especially complicated or mysterious; his motives are usually pretty obvious. The sum total of the sweeping sociological opining in the book comes in its final lines, when Guinn writes, "The unsettling 1960s didn't create Charlie, but they made it possible for him to bloom in full, malignant flower. In every sense, one theme runs through and defines his life: Charlie Manson was always the wrong man in the right place at the right time." Brief, but exactly to the point.

Manson claimed to have been a neglected child, the illegitimate son of a prostitute fobbed off on an unfeeling extended family. (In fact, his mother was married when he was born, just not to his biological father, and Guinn doubts she engaged in anything more than occasional prostitution, if that.) Guinn was able to substantiate some of Manson's stories. For example, while Manson was living with relatives in a working-class West Virginia town, his uncle punished him for crying by forcing him to wear a dress.

But Manson's cousin also remembers him as a relentlessly self-serving boy, "obsessed with being the center of attention" and prone to frighteningly violent rages. He "liked to start trouble and then let somebody else get blamed for it" at school, where she felt obliged to defend him against the bigger boys he antagonized. Although Guinn doesn't use the word until that final paragraph, the Charles Manson he describes is a classic sociopath: manipulative yet incapable of caring about or even being interested in other people, apart from how he could make use of them.

Manson started his life of crime at the age of 13, breaking into stores to rifle cash registers, then quickly escalating to armed robbery. He also exhibited a lifelong propensity for stupidly getting caught; his cleverness, such as it was, seems to have been strictly limited to talking people into things. He was in and out of reform school and prison before washing up in the San Francisco Bay Area in 1967, just in time for the Summer of Love and a massive influx of dissatisfied, drifting young people in search of spiritual mentors.

Before he landed in the milieu that would make him infamous, however, Manson studied up on two vernacular self-help creeds that would sharpen his persuasive skills to a bleeding edge: Scientology and Dale Carnegie's formula for winning friends and influencing people. Taking a Carnegie course in prison seems to have been the one instance in which Manson showed any academic zeal, and Guinn finds much evidence that he applied Carnegie's techniques to recruit and control his followers.

Manson's great ambition was to become a rock star; this, he believed, would win him adulation on the scale that he deserved. As he deployed a fusion of Carnegie-style ingratiation and flower-power mumbo-jumbo to win over a small cadre of (mostly female) followers, he always kept one eye on the prize of a recording contract. In prison, he had befriended several pimps, who told him how to target young women "with self-image or Daddy problems who'd buy into come-ons from a smooth talker": how to woo them with flattery, break down their wills with strategic beatings and isolate them from family and friends. He and his entourage soon left the Bay Area for Los Angeles, seeking contact with record-company bigwigs.

Manson did eventually acquire some male disciples -- Charles "Tex" Watson executed most of his homicidal operations -- but as Guinn tells it, the foundation of Manson's power was his astounding ability to get his "girls" to do whatever he wanted. Women did most of the work in the Family's various squats and hideouts, and their sexual services were his currency. Outsiders -- from rock stars, like Beach Boys drummer Dennis Wilson, to big- and small-time producers, bikers, landlords and other potentially useful men -- were effectively paid off in the favors of female Family members who had been trained to comply cheerfully with any sexual demand. Male followers (skilled mechanics were in particular demand, since the group had a lot of vehicles, most of them stolen) were lured into the flock by the promise of free-flowing drugs and sex, all orchestrated by Manson.

Manson had no particular musical talent, and even the music-industry professionals he managed to impress tended to see his forte as personal magnetism rather than songwriting or performing. It was inevitable that his delusional dreams of stardom would collapse. At the same time, the Family followed the predictable arc of all such cults of personality; into ever more elaborate paranoid fantasies, isolation and, finally, violence conceived of as self-defense. Manson interpreted the pop song "Helter Skelter" as a message from the Beatles confirming his prophecy of a coming race war. After Helter Skelter, blacks would take over the world, then realize that they were incapable of running it and seek out Manson and the Family to exalt as their leaders. (In addition to his male supremacism, Manson was a racist, though he only bothered to hide the latter from his girls.)

The first murder committed by the Family in July 1969 resulted from a dispute over drug money; Manson ordered followers to leave behind signs implicating the Black Panthers in the hope that this would set off Helter Skelter. When that failed, he sent out small groups on August 8 and 9 with instructions to kill the inhabitants of two different houses. The five victims of that first night included Sharon Tate, the pregnant wife of film director Roman Polanski, who happened to be renting a house once occupied by rock producer Terry Melcher. The two people killed the following night, a middle-aged couple named Leno and Rosemary LaBianca, were chosen at random. Slogans meant to signal the advent of the predicted race war were smeared on the walls in their blood, and their corpses were mutilated.

Eventually, a combination of blunders, bragging and informants led to the Manson Family's capture, and the last three chapters of "Manson" are taken up with a concise account of the joint murder trial of Manson and three of his female followers, largely sourced from the bestselling book, "Helter Skelter" by prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi. The bizarre, carnivalesque courtroom antics of Manson and his girls -- who chanted in unison at his command, and followed him in branding their foreheads with Xs and shaving off their hair -- were nearly as frightening as the murders themselves. These were people so gleefully crazed that their behavior made no sense and therefore could never be guarded against. They would kill you for no reason at all, then babble like demented witches about the end of the world.

What made the Manson Family look like something more than a small, albeit dangerous, pack of lunatics were the times. Guinn hits all the expected beats in painting the doomy panorama of the late 1960s: the war, the protests, the riots, the assassinations, Watts, Days of Rage, Chicago, Altamont, Kent State. The Manson Family felt, if you were not a hippie or a sympathizer yourself, like the dark culmination of the Summer of Love just as the killing at Altamont was the shadow cast by Woodstock.

I can't say Guinn reproduces the mood of that moment the way Didion does. But his overlay of methodical reconstruction, his deliberate and consistent minimizing of Manson's much-ballyhooed evil as the product of pathological vanity, spite and selfishness, is actually more welcome than the usual apocalyptic thunder. The times gave Manson his power, Guinn concedes, by supplying him with an ample stream of vulnerable, gullible, idealistic young people to con and warp. But Manson himself was not that special, a "social predator" and "opportunistic sociopath," as Guinn puts it, who longed to be Jim Morrison. He had to settle for the bogeyman instead.

Shares