Thanks to New York’s supermarket-style tabloid press, we now know everything about the Biogenesis performance enhancing drug scandal except whether or not the drugs enhance performance. Is it relevant at this point to stop and ask whether anyone – owners, the players union, the press – really knows what these drugs do and what the hard evidence is of any impact they have on the game?

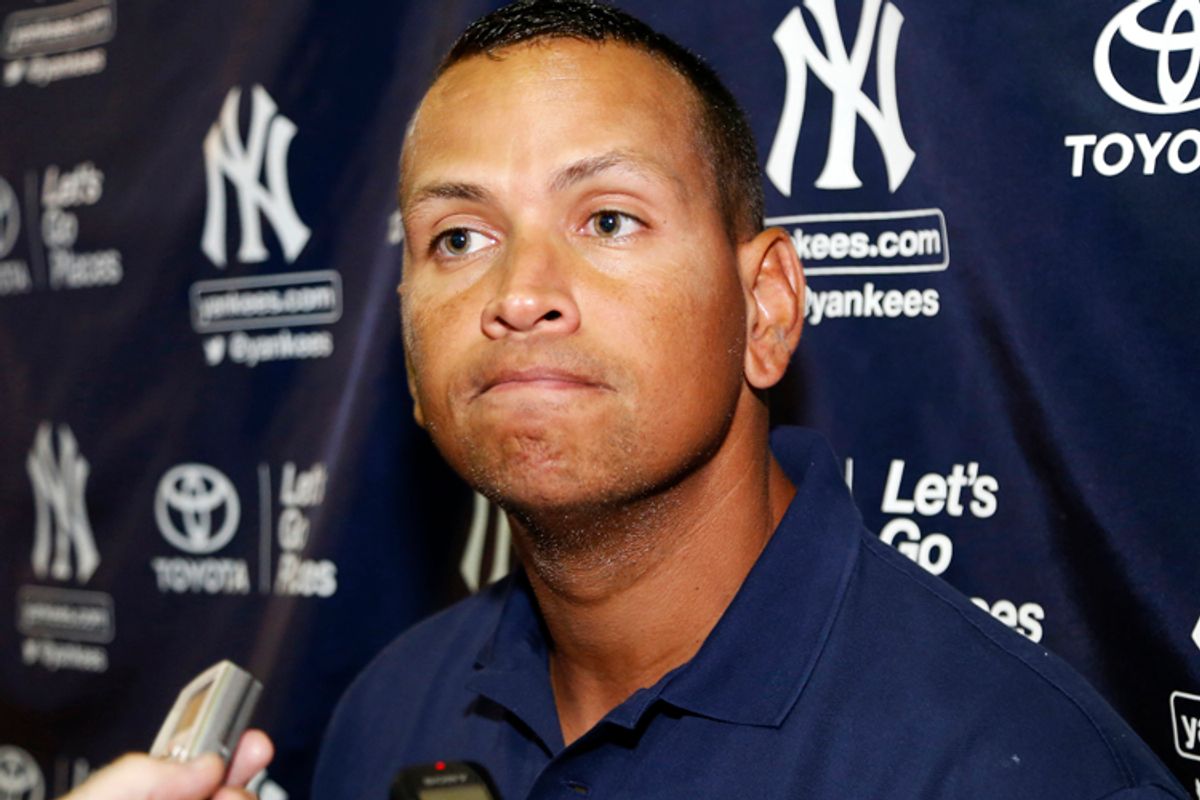

First, not every player has used the same drugs or in the same combination. The truth is we don’t know exactly what Alex Rodriguez and the other 12 players – make that 13 if you include the Brewers’ Ryan Braun -- suspended yesterday by Major League Baseball -- have taken or are accused of taking. (Most sources seem to agree that Rodriguez was looking for human growth hormone – more on this shortly.)

Second, many of the people who distribute the so-called PEDs are cranks, quacks or frauds – apparently like Biogenesis founder Anthony Bosch. I’m fairly certain that Lance Armstrong had the money and connections to get himself some first-rate advice and leading-edge chemicals, but what have Major League Baseball players been paying for?

And what is the proof that anything they are taking makes them better ballplayers? Specifically, what is the proof that these drugs enhance the most important factor in baseball success, hand-to-eye coordination?

There is only one player in the PED era who unequivocally got a boost from whatever he took: Barry Bonds. Bonds was a better player from age 35 through 40 than he was from age 25 through 30. I can’t think of another player in baseball, in fact, another professional athlete in any sport about whom this can be said.

Let me take this a step further. Barry Bonds became the greatest player in baseball history after he was 35. I’ve read stories about his work ethic and training methods, and it’s all very impressive, but I don’t see how any kind of weight training or flexibility exercise or vitamin shakes can make an athlete better at 40 than they were at 30.

But Bonds was a test rat for the most sophisticated state-of-the-art lab in sports doping, Balco. Who knows where other athletes have gotten their drugs or whether they really derived any tangible benefit from them?

Jose Canseco is the self-proclaimed poster boy for PEDs and the first to brag about his drug use. But all that Canseco may have done, ironically, is shut the door on a possible Hall of Fame bid based on career statistics that might have been entirely legitimate. Jose had a fine major league career. His batting average was just .266, but his forte wasn’t hitting for average. He had 462 career home runs and hit more than 40 home runs three seasons, reaching a high of 46 in 1998.

None of these numbers, however, are so remarkable that they require an artificial boost to explain. Let’s look at a similar hitter from a different era, Hall of Famer Eddie Matthews, who played from 1962 to 1968. Like Canseco, Matthews played 17 seasons. His career average was .271, five points higher than Jose’s, and he had 512 career homers, reaching a season high of 47. Who doped up Eddie Matthews?

How about Roger Clemens? Much is made of Clemens’ late career performance, with baseball writers who never liked him eager to attribute his success to PEDs. In 2005, Clemens was 42 and a superb pitcher, winning 13 games and losing eight. Forty years ago, Warren Spahn, age 42, was 23-7. Who doped Warren Spahn?

There is, of course, the late 1990s home run explosion, when an absurdly bulked-up Mark McGwire hit a single season home run record, 70, in 1998. But how much did creatine supplements and whatever else McGwire was taking really help him? Eleven years earlier, as a lean rookie, McGwire hit 49 home runs.

The 1998 hitting explosion is almost unanimously attributed to PEDs with major league teams averaging 4.79 runs per game. There are a lot of factors that could explain this besides PEDS: new hitter-friendly ballparks, legitimate conditioning and weight training, changes in the strike zone, et al. Now, 15 years later, sportswriters don’t want to take the time to research and analyze these factors or consider explanations that don’t involve drugs. But in 1930, hitting really exploded in baseball with each team averaging 5.5 runs per game. Who doped Babe Ruth, Rogers Hornsby, Lou Gehrig and Jimmie Foxx?

Let’s take a quick look at what PEDs are supposed to have done for Alex Rodriguez. In 2009, when his positive urine test from the 2003 season was leaked to the press, I did a piece in the Wall Street Journal on the boost drugs were supposed to have given A-Rod. Here’s what I found:

“From 1998 to 2000, while playing for the Seattle Mariners, he hit just 51 home runs in his two home ball parks (the Mariners moved in July 1999) and 74 home runs on the road. As ESPN.com's Rob Neyer notes, statistics generated on the road are ‘usually considered a more genuine measure of a hitter's power, as a single ball park might inflate or deflate home run totals.’ From 2001 to 2003, after being traded to the Texas Rangers and playing his home games at The Ballpark at Arlington, Texas -- regarded as a hitter's park -- he hit 86 home runs at home and 70 on the road.

If the PEDs A-Rod took increased his power in his home park, one wonders why they did nothing to improve his power in other American League stadiums.”

Is it fair to ask why, if Rodriguez has been on PEDS for the last two injury-plagued seasons, he has hit just 34 home runs in 221 games? The answer may well be that whatever he took, it wasn’t anything that was performance enhancing.

If the rumors that have gotten back to us about the Biogenesis evidence and what Bosch was selling is correct, the drug the ballplayers were looking for was HGH or human growth hormones. Lengthy technical articles have been written about HGH, but there are two main points about it that don’t seem to be in dispute and which the media, particularly the sports media, can't seem to get through its collective head.

HGH is not, repeat not – are you listening New York Post and Daily News? – a steroid. And there is no evidence – let’s repeat that, no evidence – that HGH enhances athletic performance. You can read the short form yourself in a 2008 article in the Annals of Internal Medicine, “Claims that growth hormone enhances physical performance are not supported by the scientific literature.”

Another quality attributed by some to HGH is its healing benefits. According to Robert Costa, professor of biochemistry and molecular genetics at the University of Illinois at Chicago, in the Dec. 4, 2004, Science Daily, HGH ”activates a gene critical for the body's tissues to heal and regenerate.”

Not every professional agrees with this assessment, and that’s the point: Like nearly every other drug drawn into the PED debate, not enough is known about HGH and its possible adverse side effects.

Surely, though, a difference can be perceived between a player trying to get an unfair advantage from steroids and one who, like A-Rod, might have been looking for a faster way back from several seasons of hip and knee problems with four surgeries in the last three years. (HGH is also what Andy Pettitte admitted to using when he was trying to come back from an elbow injury and is what Clemens is alleged to have used.)

I’m not arguing that HGH shouldn’t be on the list of banned substances agreed upon by MLB and the Players Association, if only because it might prove to be dangerous to the user. I’m not arguing that there shouldn’t be a set punishment for HGH use that is strictly enforced. I’m not saying that Alex Rodriquez is innocent.

I am suggesting that everyone might benefit from an in-depth study on HGH and other drugs so that when talk is bandied about banning someone from their profession for life, the opinions might be based on fact instead of rumor, resentment and ignorance.

Shares