The day of the Garretts’ eviction began as an unforgiving Michigan morning. It was bitterly cold, about 25 degrees Fahrenheit. The roads were so slick that a driver on the East Side had already crashed into a utility pole and died before most of the city even woke. On Bertha and William’s street, an inch of packed snow blanketed the front yards and roofs of the neighborhood, and ice tinged the branches of the leafless trees. The whole world looked grey and bleak, except for Bertha and William’s front lawn. It was buzzing with energy.

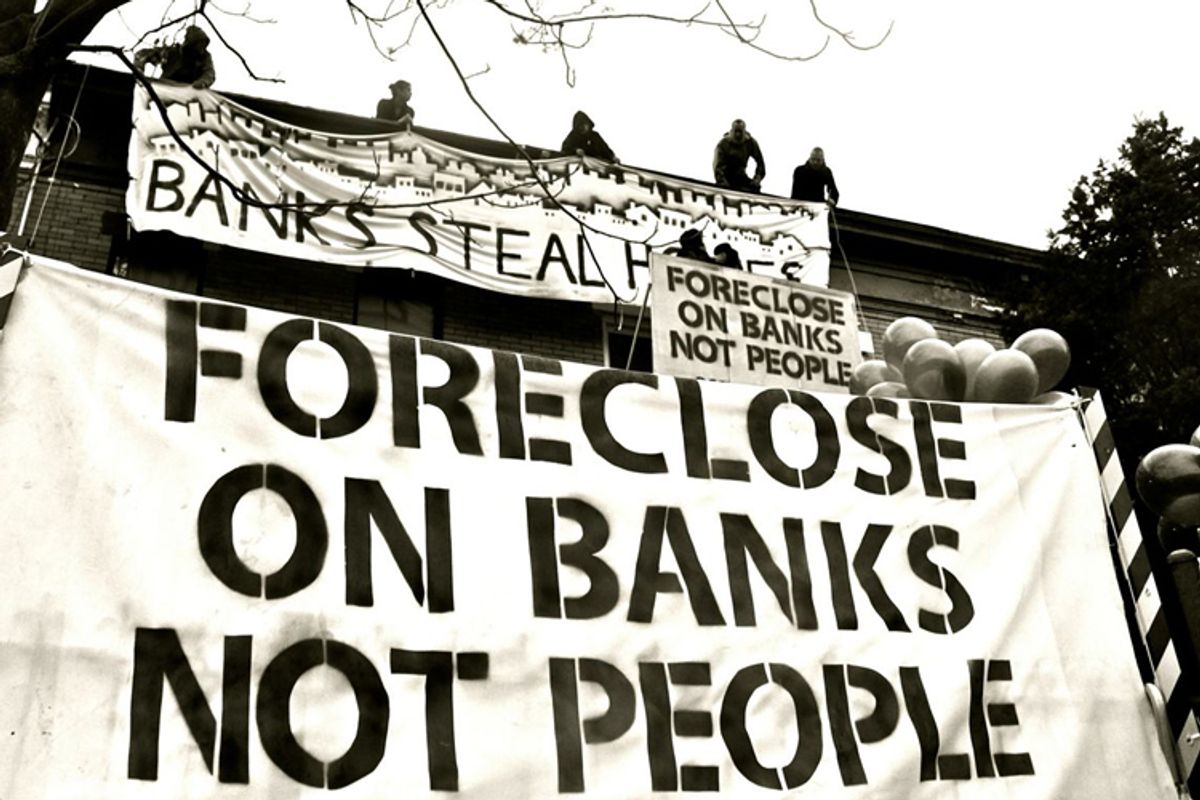

A small crowd had amassed, the freezing people stamping their feet and hunching over small cups of steaming coffee that were delivered by Bertha’s neighbors. Willie and Tommy McDade from up the street were there, Willie wrapped in a purple-and-yellow- checkered scarf. A.J. Freer, the vice president of the United Auto Workers Local 600, mingled with a handful of workers from his union. A younger crowd, some sporting Occupy Detroit patches, clustered together, talking about the plans. One driver with the Teamsters Union had arrived at 4:30 a.m. just in case things got started early.

The action had been thrown together at nearly the last moment, and no one knew how it would play out. The previous Friday— only three days earlier—Michelle had called Eric Campbell, a reporter at the Michigan Citizen, to explain the impending eviction. Campbell started making calls. Bertha, meanwhile, finally told her husband, William, about the eviction and her and Michelle’s plan to fight it. He agreed.

“Just telling me I got to up and leave ... I just can’t see it,” he said. “I can’t understand it. We got a lot of love in this house. We watch out for each other. I can walk the street over here, being a blind man, and I feel pretty secure,” he paused as his voice caught in his throat. “I get a little emotional, because everybody watches out for me ... I just can’t see walking away from what I’ve worked for for years. I just can’t do it. I’m tired of seeing the bank and the mortgage companies distress this Detroit. I’m not going to walk away from this. I’m going to fight for it. I’m going to fight till my last breath.”

By Saturday night, all the local activist and community groups were gathered together in Bertha’s home: Moratorium Now!, People Before Banks, Occupy Detroit, Jobs for Justice, and the United Auto Workers Union Local 600. Because the crisis hit Detroit earlier and harder than other places, the city has a vast network of housing groups, some of which have been at the forefront of the growing national movement since well before Occupy began. Detroit’s local union branches, too, are some of the most radical of any in the country, and the UAW Local 600 had a long history of political and social activism.

“Unions used to be groups that championed social issues, not just groups that negotiated really good contracts,” said A.J. Freer, the second vice president of the Local 600. He considered the effort to reestablish unions as the guardians of society to be just as important to his job as representing his own workers—both for the good of his city and for the future of unions themselves.

Still, two days didn’t give the group much time to work with. Reverend Charles Williams, a prominent local pastor at King Solomon Missionary Baptist Church, organized a prayer circle for Sunday night to give Bertha courage. Others were more straightforward.

“Occupy Detroit was honest with me,” said Bertha. “There was no false hope. It was last-minute, they said, but they’d try.”

Refused to move

A truck pulling an enormous construction dumpster came rumbling down Pierson Street around mid-morning on Monday. That was the moment everyone was waiting for. In Detroit, a city ordinance states that a dumpster must be placed in front of the foreclosed house in order to proceed with the eviction, meaning that if the dumpster is blocked, so too is the process of evicting people from their homes. As the truck approached, one car, and then a second, screeched to a stop in the middle of the street, parking laterally to prevent the dumpster from reaching the house. A young man ran down the road and jumped onto the driver’s side of the truck, shouting for him to turn around. The crowd of people rushed into the street. An older man with Parkinson’s disease planted himself in front of the truck’s bumper and shook his fist.

“It was crazy,” remembers Joe McGuire, a law student who worked with Occupy Detroit. “It’s one thing to know academically [what a blockade is], but to see it is another thing.”

The driver circled the block, trying to park the dumpster nearby. But Bertha’s neighbors were prepared. One man told the driver that he couldn’t park that shit in front of his house. Others agreed. Blocked and confused, the driver finally left.

Michael Shane, one of Bertha’s neighbors and an organizer with Moratorium Now!, called Bertha to tell her that the dumpster had left—for now.

As neighbors and supporters blocked the dumpster from reaching her house, Bertha stood in a hallway inside the imposing Dime Building in Detroit’s downtown financial district. Completed in 1912, the building is a twenty-three-story steel-frame skyscraper initially named after its first primary tenant, the Dime Savings Bank. In 2009, it was renamed the Chrysler Building when executives at the auto manufacturer moved into the top two floors, but the new name didn’t change the building’s symbolism as Wall Street’s outpost in Detroit. And in a small office on the ninth floor was Bank of New York Mellon’s local headquarters.

Outside of the Dime Building, about two dozen people stood shivering and holding signs reading, STOP THE EVICTION OF THE GARRETT FAMILY. Inside, Bertha was camped out on the ninth floor, waiting to speak to a representative about her mortgage contract. She had leverage now; a crowd of protesters had just turned away the city’s dumpster and halted the bank’s intended eviction. Yet the secretary informed Bertha that she would not be allowed in. No one was available to see her today. From the hallway, the little office looked about as far away from the center of global capital as one could get, but Bertha realized that it still operated under the same rules of exclusion and faceless bureaucracy.

“I watched the men go in and out, and I just thought: Well, if I can’t go in, then they can’t come out,” she said.

With that thought in her mind, sixty-five-year-old Bertha Garrett, decked out in her elegant winter coat and cream-colored fur hat, lay down in front of the door to the office of the Bank of New York Mellon Corporation in the Financial District of Detroit, and she refused to move.

Not Expendable

The term “eviction blockade” is not a metaphor. As Bertha’s splayed body and the dumpster-blocking crowd demonstrate, eviction blockades are physical, embodied actions designed to prevent authorities from seizing control of a family’s home. Housing activists in the United States have used the tactic of eviction blockades for nearly a century, if not longer, and they are once again spreading across the country as a definitive tactic of the housing movement.

Each eviction blockade has its own story. In Toledo, a man sealed himself into his own home with cinder blocks and cement, forcing the police to spend days trying to get him out. In Minneapolis, one woman defiantly planted a garden in her backyard a few weeks before her scheduled eviction to demonstrate that she was not going to leave. In New York City, waves of people halted auctions of bank-foreclosed homes by singing in the courtrooms.

Sometimes eviction blockades are not just physical actions, but also life-changing moments of bravery.

“I’ve been bullied all my life,” said Scot Johnson, one of the residents of the Riverdale Mobile Home Trailer Park in rural Pennsylvania. A quiet, feline-looking man, Johnson had been abused as a child by his father, he confided. Later, he was pushed around by the state, which seized his family’s land to build a highway. Then the abuse came from aggressive landlords. Finally, when he heard that he was to be displaced from his trailer because a water extraction company had bought the land to expand the region’s fracking industry, it was the last straw.

“As you can imagine, I’m getting tired of being pushed around by corporations, schools, the government—anyone that thinks they can push us around,” he said. Rather than move, he helped run a round-the-clock eviction blockade that lasted weeks. Adjacent to the highway that bordered the park, two other blockading residents, ten-year-old twins Amanda and Chevelle Eck, painted a sign that captured the spirit of not just Johnson’s experience but of all eviction blockades.

The sign read: WE ARE NOT EXPENDABLE.

Some eviction blockades go beyond signs and crowds and use “hard locks”—such as chains and bicycle locks—to make it much more difficult to move the protesters’ bodies. In Minneapolis, the Cruz family defended their home from eviction for months with the help of friends, neighbors and multiple hard lockdowns. In one of the many successful defense actions, eight sheriff department officers slammed a battering ram though the front door of the house at 4:00 a.m. only to find two people locked to the peak of the house’s steep shingled roof and another two with their necks locked to the bars of the second-floor balcony. All four were extricated from their locks with jackhammers and electric saws, a process that provided enough time for hundreds of neighbors to amass at the home and reoccupy it through the backdoor.

Hard lockdowns are not for the faint of heart. The most popular method is to cuff a person’s neck to a structure with a bicycle U-lock, such as the two did on the railing. Police have to sever the metal, which is only inches from one’s neck, with diamond saws, jackhammers, or “jaws of life”— cutters powered by piston-rod hydraulics used to rescue people from car crashes and collapsed buildings. In the 1980s, Greenpeace began using even more secure lockboxes such as “metal sleeves” to block chemical weapons shipments. It can take the police hours to cut through the reinforced metal, so officers will often use “pain compliance,” assaulting people with pepper spray or other types of physical and psychological abuse in an attempt to coerce them to unlock themselves.

During these moments, blockades throw an actual wrench in the system, temporarily halting auction sales or evictions by pitting people’s bodies against the mechanisms of global capital. Yet the longer-lasting power of eviction defense actions comes from the moral crisis that they create for those who witness them. Viewers are suddenly forced to see the violence that lies at the heart of society’s current housing system, evils that rarely manifest themselves because the people rarely resist.

Call off the Dogs

By illuminating this moral crisis for neighbors and the larger community, eviction defense efforts can force the bankers to the negotiation table, where they must confront a community’s demands. In Bertha’s case, the demand was for Bank of New York Mellon to sell her the house for the auction price of $12,000. But her action was also just one piece of a growing national campaign with much bigger demands: state moratoriums on foreclosures, followed by widespread principal reduction for all home mortgage-holders.

Actions linked to these demands are gaining momentum across the country as people realize the full social and economic impacts of continued foreclosures and evictions, not just on families but also on the broader society. Even the U.S. Treasury Department has come out in support of widespread principal reductions, arguing that reducing the mortgages will be less costly for the government than continuing the foreclosure process. Many housing activists know that a principal-reduction plan won’t fully confront the injustices of the for-profit housing system. It would act as a reset button for current mortgage-holding families, but it risks ignoring a third of Americans who don’t have the luxury of challenging their home’s foreclosure to begin with.

The theoretical power of principal reduction, however, is in demonstrating that economic contracts are not immutable, that with enough outcry and organizing, any economic reality can be renegotiated for the public good. In the wake of the economic crisis, citizens of other countries have already won these types of victories. Iceland, for example, structurally reduced the mortgage debts of more than one-quarter of the country’s mortgage-holding families, a reduction in loans totaling 13 percent of the country’s gross domestic product. Spain enacted a two-year moratorium on evictions for any family in circumstances of “extreme necessity” after a spate of suicides in 2012 that was not unlike the wave of foreclosure-related suicides that swept the country in 2011 and 2012. Here in the United States, this type economic shift may appear to be lofty and seemingly impossible goal—except for those who make it happen in their own lives.

“They want you to call off the dogs,” Bertha’s lawyer told her over the phone the morning after the eviction blockade. It was around 9:30 a.m. on Tuesday, and Bertha was sitting at the city council building waiting to speak out against her eviction. In her front yard, an even larger crowd had amassed than the one present the day before, just in case the city tried to deliver the dumpster. But the precaution was unnecessary. Bank of New York Mellon’s lawyers had called. They were tired of the articles and the phone calls; they didn’t need any more bad press. If Bertha wanted the house for $12,000, she could have it.

“I’m trying to laugh, but I’m hyperventilating,” Bertha remembers. For the days that followed, she could barely contain her emotions.

At a celebration in front of the house the following day, Bertha explained how she felt when she first heard that the bank’s lawyers had capitulated.

“I felt like shouting. I felt like running down this street ... Your presence gave me strength to fight. And my daughter and my neighbors, they gave me strength to fight. And the prayers of everyone that prayed for me. So how do I feel? I feel like dancing! I feel like shouting! I feel like worshiping God, that’s how I feel! I feel good! I feel like that house has been lifted off my shoulders. I feel like I can help my husband now without every day wondering: Do I tell him that he has to move? How do I tell him without him falling down and having a stroke? That’s what I feel like.”

A few weeks later, Bertha signed the paperwork to buy her home back from Bank of New York Mellon for $12,000. Her whole sixty-five-year-old body felt numb as she scrawled her signature in order to finally be safe in the place that was already her home.

Excerpted with permission from "A Dream Foreclosed" by Laura Gottesdiener. Copyright 2013, Zuccotti Park Press.

Shares