"Every night in every city, children are buckled into vans or police cars (like criminals), as wards of the state (like criminals) and driven to strangers' houses and told to behave. Children explain this to themselves in a myriad of ways: often, because they're children, it's because of something they did. ... And almost always, the kids get no real explanation."

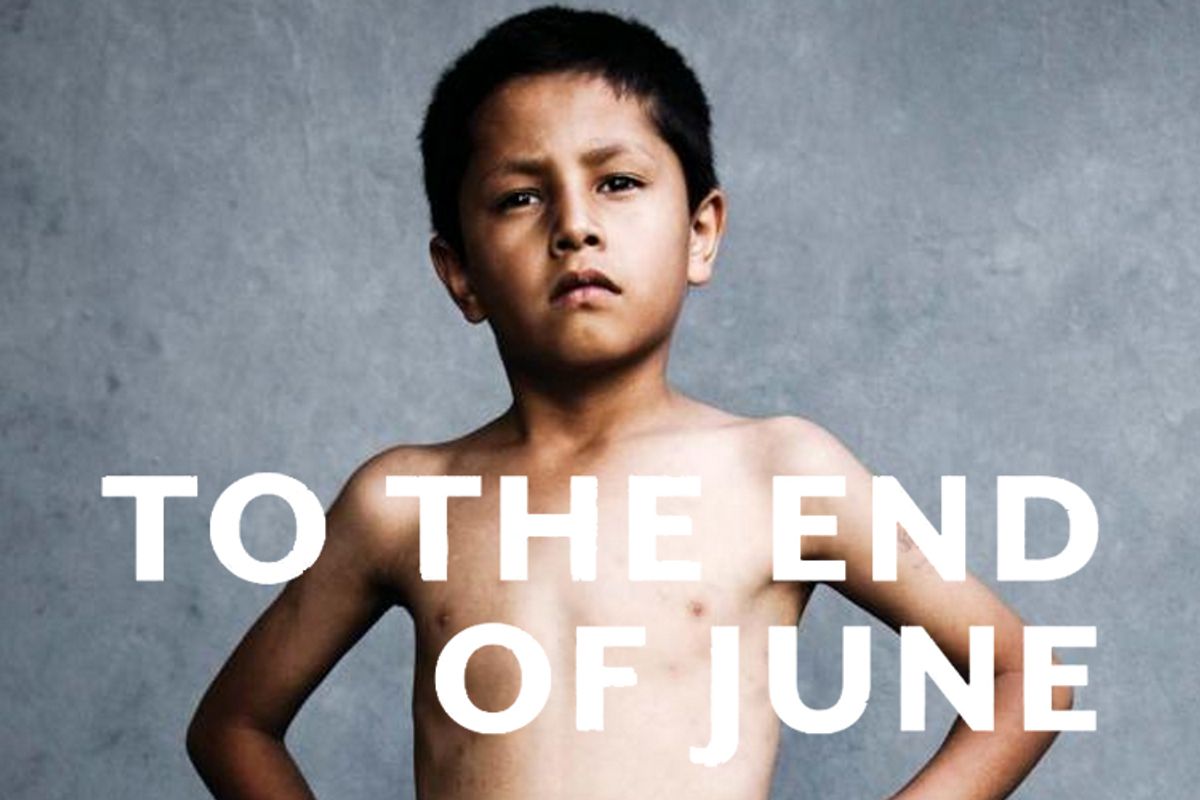

So writes Cris Beam in her heart-rending and tentatively hopeful new book, "To the End of June: The Intimate Life of American Foster Care." In 2011, over 400,000 children were in foster care nationwide (down, promisingly, from 488,285 in 2007), but "the system," as those who find themselves mixed up with the child welfare apparatus usually call it, rarely comes to public attention -- except when a dramatic failure hits the headlines, usually the death of a small child from parental abuse. (In New York, Elisa Izquierdo, Nixmary Brown and Marchella Pierce have been some of the most iconic victims.) Beam calls the uproars following such murders "Foster Care Panic," and the three or four years they last typically see an uptick in "removals," those scenes with the vans and police cars described above. The panics also sometimes bring about much needed reforms, but it's impossible to reach the end of "To the End of June" feeling that removal is much of a solution.

"To the End of June" is part history and overview, part in-depth portraits of foster children and parents. Beam, although never a foster child herself, left her emotionally disturbed mother's house at the age of 14 and never saw her mom again. Then, at 29, she became a foster parent, taking in a former student, a transgender teenager she now considers her daughter.

In researching this book, Beam spent considerable time over several years with a married couple in Brooklyn, N.Y., the Greens, who took in multiple foster children (in addition to their three biological children). She also visited the household of Mary Keane, a woman who bought a 12-bedroom Victorian house in Yonkers to provide a home for foster children (including six siblings from an abusive mother), several of whom she has adopted. Beam spoke to case workers, therapists, former foster children and other people who know what the system is like from the inside.

Some of what Beam finds is unsurprising: Poverty is the main determinant in whether or not a child will end up in foster care, and for that reason racial minorities tend to be overrepresented in the ranks of families involved in the child welfare system. Foster families can be loving, but they can also be mercenary and impersonal (foster parents receive modest regular payments from the state to support their charges) or downright dangerous. Others do everything they can to provide the children they foster with nurturing environments, only to have their hearts broken when the biological parents reenter the picture and try to regain custody. Some foster children thrive in their new homes, but many never recover from their rocky youths and end up repeating parental patterns of substance abuse, homelessness or crime.

Although she's far from doctrinaire about it, Beam comes down on the side of what's known as a "family-based model" of child welfare, which insists "we should make every effort to keep the biological family together." "We realize now," one advocate tells her, "that the outcomes for children in foster care are going to be worse than if they had stayed in the home. Even if there was some neglect." A former foster child explains, "If you have the choice of being abused by your mother or abused by a stranger, you'd choose your mother." The better solution, of course, is to focus resources on helping parents keep and care for their kids, rather than on removing them from their homes.

Recalling her own lifelong guilt over leaving her own mother, Beam is acutely aware of "all the kids I knew who mourned the separation from their biological parents and acted out all kinds of terrible things from that loss." As dysfunctional as some of those parents were, many foster kids feel compelled to seek them out again when they're old enough to try. "They've been abandoned in some fundamental way, and yet the biological bond is very much alive." Despite this position, however, Beam describes rooting for a friend who fostered an infant in hopes of adopting the boy, then had to wait on tenterhooks while the child's feckless young biological mother tried (and ultimately failed) to regain him. Every case is different and complex, which is probably why the media only pays attention to those stories where a clear-cut villain makes snap judgment possible.

At the core of the question of what's best for a kid lies attachment, the profound emotional bond between a child and his or her primary caregiver. The rupture of this bond can lead to a lifelong difficulty with trusting others. The worst possible scenario -- which is all too common -- sees kids moved from one foster family to another, sometimes running through as many as 20 or 25, and unable to form any attachment at all. One girl Beam meets had finally found a caring foster mother at age 5, then was briefly reclaimed by her biological mother. When the mother relapsed, the girl was not sent back to the woman with whom she'd formed a connection because her case was picked up by a different agency, "likely whichever one had space on its roster."

It's no wonder that most of the foster kids Beam meets regard the Administration for Children's Services (New York's child welfare overseer) as a frightening entity that has destroyed their lives over and over again. Beam sat in on a hearing in which a young mother trying to regain her baby was grilled in great detail about the drinking and pot smoking of a boyfriend she'd since ejected from her life. "Foster care has always favored safe housing over psychological stability," Beam writes, and during panic periods, it can go overboard in defining "safe." On the other hand, "safe" is a lot easier to quantify and regulate than psychological stability or bonding.

Once foster children reach their teens, they become more difficult than ever to place with a family and can end up relegated to group homes or residential treatment centers, locked facilities that also house juvenile delinquents. Fostered teens can be oppositional and even destructive under the best of circumstances. Unfortunately, most group homes (and some foster homes) too often respond to such misbehavior as a matter of "responsibilities and consequences" rather than as a sign of unprocessed trauma and grief. "Foster kids usually believe they caused their biological family to tumble from orbit," Beam explains, "so of course they could dislodge a foster family, too. ... They'll keep pushing for that weak spot again and again until someone stands up and says, 'I will love you anyway. Stay.'"

It takes a remarkable and selfless person to volunteer for that job. "You do it because you want to help a kid and because you enjoy seeing them grow," Mary Keane tells Beam. "The gratitude for what you've done might come later. Like after five years of hell." Some of the most giving foster families, like the Greens, are people of faith. But while the couple is affectionate and generous, they also see themselves as erecting a moral bulwark against a corrupt world, and they impose strict curfews and house rules on their charges.

The Greens' teenage girls bridle under this regimen, and when the kids rebel or skip class or get drawn back into the perilous orbits of the biological parents, their foster mother can only respond with scriptural quotations. ("No matter what it is," her foster daughter complains. "I have a headache. She'll say the reason's in the Bible.") The same structure that provides her kids with the stability they secretly crave proves too brittle to withstand the buffets of their adolescence. On the other hand, gratitude could indeed come later, as it has for many a biological parent.

"To the End of June" is cautious rather than tendentious, welcoming (with reservations) such policy changes as a switch to "waiver operations," in which the state pays agencies a flat fee for handling its child welfare needs, rather than per-child allotments, which offer an (unintended) incentive to keep kids in the system. This, Beam believes, will encourage investment in "preventive services" designed to keep families together whenever possible. Other projects, like You Gotta Believe! in Brooklyn, try to save older foster children by concentrating on locating the person "who cares about this kid" (anyone from an older sibling to a former teacher or neighbor) and developing and reinforcing that relationship. Bureaucracy and love make strange bedfellows, but love -- committed, patient, forgiving -- Beam argues, is the only thing that can do the job.

Shares