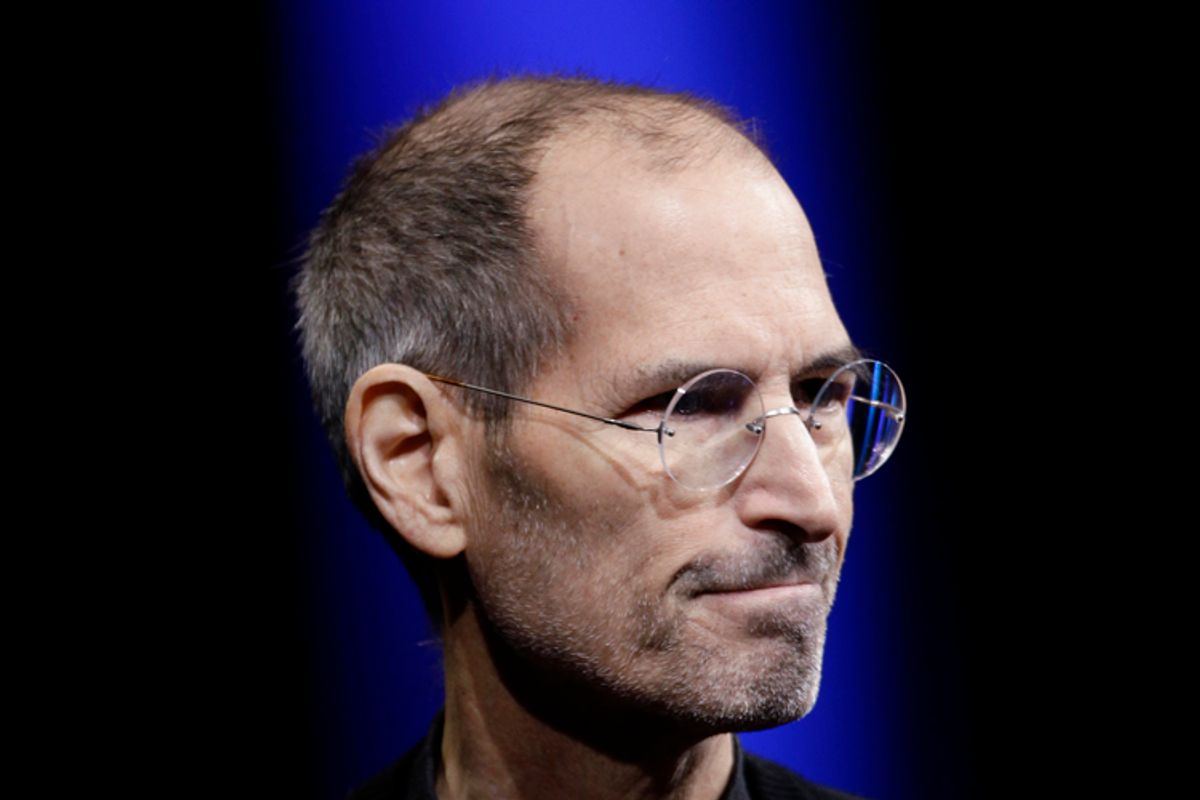

Steve Jobs’ first experience designing telephones involves the now famous story of the “blue box” device. In the early 1970s, Jobs’ friend Steve Wozniak was captivated by an Esquire story about the creator of a phone-hacking device that made it possible to dial long distance calls for free. Wozniak got to work on his own version of the device right away using his own components. Jobs and Wozniak invited John Draper, aka “Captain Crunch,” one of the mysterious men featured in the Esquire article, to Wozniak’s Berkeley dormitory to show them how to make the box work. Draper was hesitant but ultimately acquiesced. By the end of the evening, the three intrepid hackers decided that their first call should be to the Vatican. It worked.

The Pope and the “Jesus Phone”

Thirty-five years later, Jobs would introduce the iPhone—a device that would transform the wireless telephone industry. The hacker-turned-billionaire Steve Jobs inadvertently found his prized new device linked to the Vatican again. The iPhone became the subject of a host of religious parodies, most notably earning the moniker “Jesus phone.” The godly description of Apple’s signature gadget started with a joke by Gizmodo contributor Brian Lam. Lam coined the term “Jesus phone” in a blog post, and it quickly spread through the online tech news community. The “Jesus phone” quip was posted in response to an address given by Pope Benedict XVI on Christmas morning in 2006. The Holy Father asked,

Is a Saviour needed by a humanity which has invented interactive communication, which navigates in the virtual ocean of the internet and, thanks to the most advanced modern communications technologies, has now made the Earth, our great common home, a global village? This humanity of the twenty-first century appears as a sure and self-sufficient master of its own destiny, the avid proponent of uncontested triumphs.

Benedict XVI’s comments reveal one of the fundamental tensions of the modern religion-technology relationship: transcendent redemption has been part of mythology and religion for centuries, but the source of that redemption has relocated to the scientific and technological. The Holy Father’s concern stems from humanity’s failure to provide for the basic material needs of hungry millions while millions of others engage in “unbridled consumerism.” Lam responds,

Of course we still need a Savior. Hopefully, our shepherd, Steve Jobs, will unveil Apple-Cellphone-Thingy, the true Jesus Phone—or jPhone—in two weeks, at the Macworld Keynote. It shall lift the hunger and disease you speak of from the land, as it will cure the rabid state of mind infecting Mac fanboys like yours truly.

Lam responds to the pope’s genuine appeal for reflection by co-opting the language of Christianity to describe his anticipation of technology in messianic terms. Here, Lam is engaging in the rhetorical act of “parodic allusion”—an intertextual strategy that appears throughout the divinized iPhone rhetoric.

Lam’s reflexive parody of the name Jesus is a hallmark of post-modernism. Since the advent of electronic media, the mass reproduction of messages and images has so exhausted meaningful cultural symbols that their recirculation now favors parody and ironic reference. Devices like the iPhone that become the tools by which the recirculation of cultural symbols takes place amplify this rhetorical situation. Text and images are manipulated, emailed, and messaged on the order of billions per day. Symbols and images often become Internet “memes” and go viral, making them part of the cultural lexicon overnight, “Jesus phone” being a case in point. The iPhone’s central role in the production/reproduction and circulation/recirculation of symbols grants it an elevated status worthy of sublime descriptors like “Jesus phone.” It is the symbol by which other cultural symbols are funneled and spread.

Technologies like the iPhone put us in touch with an immense, global, and decentered network. The scale of this network is only dimly perceivable. It evokes sublime descriptors like “Jesus phone” because it alludes to something that cannot be shown or presented—where the imagination fails to produce an object to match the concept. It works as both a promotional strategy (concealing the object before a highly anticipated launch) and philosophically by referring to the way in which immense telecommunications networks and the devices that harness them exceed our ability to explain their inner workings. The tendency is to fill in the blanks with terms and phrases that signify an excess of meaning or mystery.

Apple’s flair for sublime design reached a high point in 2007 with the release of the iPhone. The iPhone combines telephone, Internet browsing, email, and scores of other web applications or “apps” on a powerful pocket computer. The web functionality of iMac and the mobility of iPod converged in the iPhone, making it a must-have device. The iPhone is revered for its elegance and simplicity. The device is operated almost exclusively by touchscreen gestures. It is a shimmering block of glass and textured metal that set the standard for smartphone design.

Advertising for the iPhone was relatively sparse before the initial launch. The device was shrouded in secrecy, making the launch at the Macworld Conference in January 2007 borderline liturgical. Jobs told the audience at Macworld that the iPhone would “reinvent” the telecommunications sector, that it would “change everything,” and that he felt very fortunate to work on just one product like this in his career. The holy trinity of telephone, iPod, and Internet would ensure that millions of iPhone customers would never feel disconnected again.

The sublime used to refer to the overwhelming sensation of recognizing the divine in the wonders of nature: oceans, mountains, and stars. Poets and painters would try to capture the natural sublime in verse and on canvas, but it was an elusive experience. When it was shared by many, it provided a collective sense of awe and unity, giving some confirmation that God’s presence was something that could be experienced universally and in communion with others. The dawn of the industrial revolution shifted the center of collective wonder to the creative machines that made up the late-nineteenth-century landscape. Enormous factories, powerful machines, immense buildings and bridges humbled man in new and startling ways. An army of human creators fashioning a new Tower of Babel, a new nature, was outshining the Creator.

A new nature requires a new set of myths for coming to grips with the new environment. The myth provides a narrative means of grappling with powers that seem beyond our individual control. It also “reinvests the landscape and the works of men with transcendent significance.” For the ancients, myths helped explain the capriciousness of nature. Weather and natural disaster were concrete signs from the gods that expressed divine favor or disappointment. Threats of blackout, crashes, and crippling computer viruses are among the fears of technological man. The unsuspecting iPhone user who suddenly loses service in a dead zone or loses all of his or her contacts or, worse, loses the phone altogether enters a state of panic. This is a perfectly natural reaction to the new environment in which we are situated. Being cut off from the communication infrastructure renders one deaf, dumb, and blind in a world dependent on 24/7 connection. The messianic tone of much of the iPhone hype then stems in part from its ability to heal and deliver the technologically disabled from the state of digital darkness.

The idolatry reserved for Apple products stems from its role as privileged cultural mediator, a symptom of which is the popular rhetoric ascribing it with sublime properties. The intertextual allusion and parody present in the technology journalism surrounding the iPhone launch are also present in the company’s advertising. The lone print advertisement that preceded the launch of the iPhone was suggestive of this pattern. The ad features the tagline “Touching is believing." The scene features an illuminated iPhone projecting its light into the surrounding darkness as a finger reaches in to make physical contact with the device. The visual effect of electronic light piercing the darkness plays a central role in the symbolic construction of the ad. The ad highlights the touchscreen technology that centers the user interface on the screen itself rather than a physical keypad. The Apple smartphone redefines not only the type of content that can be experienced on a mobile device but also the sensory means by which that content is accessed and experienced.

The phrase “Touching is believing” evokes the biblical account of the apostle Thomas, who refused to believe Christ had risen from the dead until he could touch the wounds of Jesus’ crucifixion. The seventeenth-century painting by Caravaggio depicting the doubting apostle Thomas placing his finger in Christ’s wounded side is a graphical representation of the story from Scripture. According to John’s gospel account, Thomas insisted that his belief in the risen Christ was contingent on touching the actual wounds: “Except I shall see in his hands the print of the nails and put my finger into the place of the nails and put my hand into his side, I will not believe” (John 20:25). Eight days later Christ would appear to Thomas and invite him to touch: “Put in thy finger hither and see my hands. And bring hither the hand and put it into my side. And be not faithless but believing” (John 20:27).

The drama of the gospel account is parodied in the ad for iPhone and presented as an answer to the prayers of Apple fans anxious to see the new creation. In its unique positioning as a device driven almost exclusively by touchscreen commands, the linguistic signifier, “Touching is believing” and the image of the finger work together to reinforce the message that seeing the new object is not sufficient; the intimacy of touch is required to consummate the highly anticipated union between consumer and object of desire. At the literal level, the ad poses an equivalency between the sense of touch and the act of knowing. The consumer is invited to touch the device in order to confirm its existence. This works as a reference to the prelaunch marketing hype for the iPhone. The feverish anticipation surrounding the launch is encoded in the image as the simple act of touching the new phone comes to represent the culmination of a union months in the making.

The phrase “Touching is believing” evokes the idiom “seeing is believing.” While the ad copy works as a tongue-in-cheek reference to the uniqueness of the closely guarded product, a more mythological read reveals the epistemic shift that digital media favor. “Touching is believing,” like “seeing is believing,” describes a particular way of knowing. Seeing something is considered a privileged mode of determining reality or unreality. Aristotle claimed that sight gives us more knowledge and awareness than the other senses. The figures in Plato’s cave were plagued by shadows that inhibited their ability to recognize the light.

The Apple ad shows that the nature of knowing in the visual age has shifted. When images are subject to digital manipulation, it is more difficult to make claims about the authenticity of an image. This condition is exaggerated by digital imaging technologies that allow for the rapid dissemination (and potential distortion) of images. In this way, the caption in the iPhone ad makes a statement about the literal features of the product (a touchscreen) as well as the epistemic conditions of life in the age of the ever-present screen, an age in which the authenticity of screen images is constantly being called into question. The iPhone adds a tactile layer of expression to the information universe by incorporating the sense of touch and inviting the user to transcend the knowledge that comes from sight alone. “Seeing is believing” gives way to “Touching is believing.”

Consumers are invited to seek what is true by touching screens that unlock libraries of knowledge in a matter of seconds. In "The Rhetoric of Religion," Kenneth Burke writes, “ ‘[T]echnologism’ is a ‘religion’ to the extent that technology is viewed as an intrinsic good, so that its underlying, unspoken assumption is: ‘The more technology, the higher the culture.’ ” If one is disconnected from the flow of digital information, then the human need for social connection and information acquisition is amputated and the individual is left senseless, blind, deaf, dumb—unable to access the vital knowledge contained in the realm of infinite digital information.

The iPhone ad presents the phone as a hovering object, suspended over a sea of black, created ex nihilo, “out of nothing.” The hand, with one finger extended, ready to touch the glowing body of the iPhone, is visually resonant with Michelangelo’s iconography of the biblical creation account, evoking the “Creation of Adam” image that makes up part of Michelangelo’s magnificent fresco in the Sistine Chapel. In the fresco, the figure of God reaches out to touch man, the crown of creation.

Through the arrangement of signifiers in the ad, the reader is invited to more fully consider the phenomenological act of mediated communion. A creative tension emerges from the small space between the human finger and the glowing machine. One is reminded of the iconic image of the young boy reaching out to touch the glowing finger of ET in the 1982 Hollywood film. The use of touch speaks to a level of intimate contact that no other sense can provide. AT&T’s use of the tagline “reach out and touch someone” speaks to this essential feature of human communion and its usefulness for telecommunications marketers. However, in true postmodern fashion, the act of touching is only a simulation that drives a finely tuned, graphics-based user interface. The user touches nothing concrete other than a pane of glass. Nonetheless, a sense of omnipotence is granted to the user, who is able to use the device as a sort of remote control for everyday life.

The fawning and reverence reserved for the miraculous objects of modern technology are directed not at the machines themselves but at their symbolic function as supernatural enhancements to the sacred practice of human communication. Supernatural in this sense is meant to draw attention to the fact that our use of such objects allows us to transcend and exceed natural or embodied forms of human communication like human speech and physical presence. This transformation is no small matter as it places us in contact with people and information that are discarnate, without bodies. It is when we take this condition for granted that we overlook the role technology plays in reordering social relationships in such a way that human presence and actual human touch are effaced by digital simulation.

While the ad evokes a number of Christian allusions, the polysemous text could also be read as a derivation of Buddhist and gnostic belief. Because the Buddhist or gnostic views the physical world and human bodies as the source of all suffering, the digital realm represents the liberation of the mind and spirit from the prison of the body. Given Steve Jobs’ affinity for Eastern spirituality, one might make the case that this interpretation is more compelling. The power of the Apple brand and its rhetoric is the multiple resonances it embodies. The interplay of physical and metaphysical is highly influential in how modern communication technology gets imagined in popular discourse. Apple exemplifies this by depicting products in preternatural settings, abstracted from scenes of everyday life and placed in white-washed, blacked out, or surrealist environments that speak directly to the sensory separation from time and space that occurs when one engages with Apple’s immersive objects.

Rationalizing the Universe One App at a Time

Apple’s success is based in part on its ability to transform the cold rationalism and research that goes into creating its products into the mythical language of scientific magic and technological mysticism. In the promotional rhetoric of the Apple computer company, the convergence of the technological and the religious reveals a persistent dialectic at work in the American imagination between rationalism and mysticism. The aim of scientific rationalism, spawned in the wake of the religious wars of the seventeenth century, was to disenchant the world. For Descartes and other leading thinkers of the era, “reason” was a necessary antidote for a society torn apart by religious difference. Mystery and magic led only to chaos. Scientific rationalism provided a sense of order and control.

The fruit of scientific rationalism can be seen today in the proliferation of techniques and technologies that make it possible for humanity to tame nature and reduce or eliminate contingency. By eliminating contingency or attempting to control it, the capricious will of the universe is neutered and caged. The rationalist asserts that humans, enlightened and rational humans, should be arbiters and captains of their own destiny. In an ironic twist of history, it is technology that has filled the void of enchantment by offering users a share in mastering a universe drained of fables and mysteries. Max Weber summarized the situation this way: “The disenchantment of the world . . . means that principally there are no mysterious incalculable forces that come into play, but rather, that one can, in principle, master all things by calculation.” Devices like the iPhone represent more than convenient communication objects; they are symbols of a collective drive to eliminate contingency further from experience and to inherit the power of the deity: being both omnipresent, everywhere at once, and omniscient, knowing all there is to know. The quasi-supernatural power of modern technology is derived from its seemingly limitless scope.

One of the ways in which the iPhone rhetoric delivers this quasi-supernatural message is by highlighting the magical qualities of the device. In this sense, things have come full circle. One of the most popular tools we use for eliminating contingency and containing complexity is itself treated as a sacramental object in the technological order. In religious tradition, the sacramental object is something capable of mediating transcendence. Like rosaries and relics, powerful communication devices are mediators of the virtually infinite digital sphere.

The iPhone and its touchscreen interface engage the technological faithful at a heightened level of intimacy. The iPhone is not a cold and lifeless machine; it is an enchanted talisman, animated by touch. It mimics an encounter with the transcendent by mediating the infinite body of online information and communication possibilities. Text, voice, and video make others present in a condition of instant communication that borders on the telepathic and angelic. In a New York Times review of the iPhone 4S, David Pogue uses words like “mind-blowing” and “unbelievable” to describe a phone that “feels like magic.”

The themes outlined above—the disenchantment of rationalism and a lingering tendency to view technology as something magical or pseudo-religious—are combined in the Apple narrative in a way that is instructive for scholars of religion, communication, and technology. Technology advertising is rarely explicitly religious; instead, the rhetoric is cloaked in postmodern and parodic allusion that invites viewers to fill in the gaps by reassembling the scraps of cultural and religious mythologies that pepper the technological discourse.

One of the first television ads for the iPhone features a setup very similar to the “Touching is believing” print ad. The backdrop is a deep black. A close-up of the phone fills the center of the frame. For thirty seconds, the viewer is taken on a tour of the iPhone’s diverse set of features. From watching a movie to making dinner reservations, everything is a touch or swipe away. The ad focuses on the device screen that occupies the majority of the phone’s face. The shot provides the visual sensation of watching a screen (the phone) within a screen (the television). The disembodied hands that handle the device thus become a signifier for the “manipulability” of this form of digital media. The signifier of the hand challenges the convention that media devices are merely sight and sound experiences. They are things to be touched, held, and manipulated.

In the world of the iPhone, viewing a film becomes an occasion to immediately indulge a craving for seafood. During a film scene involving a murderous squid, the voiceover playfully intones “mmm . . . did someone say calamari?” Instantly, the screen of the phone changes to a map where the user is able to pinpoint the nearest seafood restaurant in an effort to satiate this impulsive desire. A couple of seconds later, the phone function is activated and the user is connecting with the restaurant. From initial biological response to contact with the restaurant, less than twenty seconds has elapsed. The iPhone is a catholicon for securing instant gratification.

The “catholic” or universal appeal of the object is a point worth considering. In the age of iPhone, there is a social obsession with efficiency via process and technology, and it is universal. Whether we own an iPhone or not, the ethic of speed and efficiency is built into nearly all of our cultural practices. Jacques Ellul points out, “Geographically and qualitatively, technique is universal in its manifestations. It is devoted, by nature and necessity, to the universal . . . it is becoming the universal language understood by all men.” Ellul comments on the sociological impact of technique as if it were something religious: “Technique, moreover, creates a bond between men. All those who follow the same technique are bound together in a tacit fraternity and all of them take the same attitude toward reality.”

Another way in which the iPhone advertising exhibits the religious resonance of life in a technological society is through the colonization of leisure, exemplified in the Apple ads featuring the multitude of downloadable apps available for the phone. Apps are individual software applications that allow iPhone users to accomplish specific tasks. There are apps that provide weather reports, others that provide driving directions, others that provide access to banking information, and so on. Over thirty billion apps have been downloaded from the “App Store.”

With hundreds of thousands of apps and counting, Apple would have us believe that there is an app for everything. The Apple website crows that there is “almost no limit to what your iPhone can do.” Categories include games, business, news, sports, health, reference, and travel. Apps are also available for the iPod and iPad. Unlike personal computing applications, mobile apps are useful in virtually any context: in a car, at the bank, on a subway. As such, the apps have the ability to add a layer of enhanced experience to any environment. Exercise apps count miles and calories that can then be uploaded to a website to track fitness progress. Some fitness apps are incorporating biofeedback measures like heart rate to further enhance the overall workout experience.

What Apple has managed to do with the iPhone and the App Store is create a realm of productivity that redefines the cultural practice of leisure. Devices like the Blackberry are seen as corporate productivity devices, while the iPhone is depicted as something more playful and imaginative. This is a trope that Apple initiated with the introduction of the first Macintosh in a predominantly business-oriented IBM world, and it still persists today. This is also where the technology as cult concept is most relevant.

The religiosity of the Apple brand community can be traced to the function of the device in the lives of users and the way it is represented in the advertising. If the iPhone is not strictly used for the purposes of accomplishing business tasks but also delivers the types of leisure activities (movies, games, cooking, exercise) sought by members of the technological society, then its role in the lives of users is something quite profound. The iPhone is a virtual remote control device that plays a central role in the leisure activities of its users. Whether making restaurant reservations, texting or calling a friend, or tracking workout performance, the sophisticated iPhone provides a multitude of ways to wield the universal remote in a variety of situations that previously lacked technological intervention. No matter the situation, it seems there is an app for it.

In the “Shazam” app commercial, a pair of hands hold an iPhone and act out the scenario being presented by the announcer: “You know when you don’t know what song is playing and it’s driving you crazy?” The anonymous user in the spot points the iPhone toward a pulsating speaker. The iPhone recognizes the song and displays all of the information on-screen. The commercial concludes with the announcer reminding the viewer that the iPhone solves “life’s dilemmas one app at a time.” Like many of the iPhone commercials, the action takes place on a white background, devoid of context. The hands appear to be male but are generic enough to signify a pair of “everyhands.” The hands denote a capable user and signify the way the device is to be used; by touching the screen, swiping with the fingers, and pressing the onscreen icons. These cues provide implicit instructions for viewers who may be unfamiliar with the iPhone’s functionality. The hands are also a metonym for the user. A part, the hands, stands for the whole person.

The hands command and conduct the machine, not through a peripheral piece of hardware like a keyboard or mouse, but through the screen itself. The hands caress the mediated icons and images as if they were physical realities. Previously, the images on-screen required hardware to manipulate; now the hands make direct contact. This action of manipulation, the etymology of which refers directly to the hands, is one of creation, or in the case of the iPhone, re-creation. The passivity of traditional media experiences gives way to the creative activity of the hands that engage the elements on-screen.

The iPhone redefines traditional leisure activities. In the “Shazam” commercial, listening to a song, once an occasion for relaxation and pleasure, is portrayed as an occasion of anxiety because not knowing a song could be “driving us crazy.” Knowing the name of the song signifies a form of ownership of that piece of culture. Furthermore, knowing the name of the song allows one literally to own the song by purchasing the artist’s recording. The iPhone streamlines this consumer process by digitizing it. Figuring out the name of the song is no longer a task accomplished by calling the radio station or asking a friend, it is something accomplished by the omniscient iPhone. This leisure activity is no longer profitable in the humanistic sense of enjoying culture for its own sake. It is deemed profitable once an acquisition has been made, either the name of the song or a recording of the song, or both. The speed at which this is accomplished is also portrayed as profitable because it provides instant gratification.

The idea of an activity being profitable in the consumerist/technologist sense counters the view of culture that privileges the practice of unmediated contemplation. For modern philosophers like Josef Pieper, the contemplation of the true and the beautiful, directed by religious ritual and observance, is a kind of rest. This kind of rest, rooted in contemplative activity, is restorative and creative. This, says Pieper, is the basis of culture and human freedom, a view that has been lost in the sea of mediated consumption that demands constant action by the user and rejects stillness and silence.

What Apple offers us in the iPhone ads is a false freedom, one that offers amusement and efficiency as counterfeit forms of human leisure. The hands in the ad are the hands of a shackled individual, one who cannot engage the real world without consulting the virtual first. They are also hands without a head. The “user” surrenders his or her intellectual expansion to the songs, movies, games, and apps that now invade the last outposts of human contemplation in contemporary culture: a subway car on the way to work, a small table in a café, a cross-country automobile ride.

It is fitting that so many clamor for phones and entertainment devices in transit. The mobilization and privatization inaugurated by the motorcar are now made available in personal technology. The devices transport the user, temporarily, from reality. What we do in the moments once reserved for reflection and contemplation becomes a de facto religion of sorts. It fills in the gaps of silence and presents a world removed from the one we are in. It is a form of existential escape. Religion, it seems, can be easily aped. By colonizing leisure, the iPhone, like the computer before it, stakes its claim as one of the bases of the technological culture.

Reading the Religion of Technology

The religion of technology bears some resemblance to Protestant eschatology. From the half-eaten Apple logo, a figure for the forbidden fruit in the Garden of Eden, to the Orwellian vision of a fallen planet of IBM drones, the Apple rhetoric seems to be saying that the earth is a fallen place and that the tools of science and technology grant us the ability to redeem and ultimately perfect our fallen state of being on the path to perfection. It grants us power over our surroundings in ways that were previously unthinkable. David Noble notes that developments like the atomic bomb and genetic engineering speak to both the creative and destructive ways in which creatures seek to imitate the creator.

The iPhone is not atomic, but it is emblematic of what Albert Einstein called the information bomb. The radioactivity of nuclear weaponry precedes the interactivity wrought by telecommunications technology. The explosion of information and digital computing has infiltrated all aspects of social and cultural life. The “fallout” of interactivity induces a radical mutation of work habits and social interaction. Ingrained patterns of social and cultural life are remade in the image and likeness of the machines that have become the new nature. In the Protestant eschatological view, this development is a positive step toward human perfection, making us more godlike by imitating omniscience and omnipresence, if only in a virtual sense. French philosopher Paul Virilio noticed a similar parallel between religion and technology:

The new technologies bring into effect the three traditional characteristics of the Divine: ubiquity, instantaneity and immediacy. Without some cultural familiarity with these themes, mediated by Christianity, Protestantism, Buddhism, Judaism, Islam, etc., they remain incomprehensible. One cannot come to grips with the phenomenon of cyberspace without some inkling of, or some respect for, metaphysical intelligence! That does not mean that you have to be converted. I believe that the new technologies demand from those who are interested in them that they have a substantial measure of religious culture and not merely some religious opinion.

In the modern age, religious beliefs are viewed as relative equals permitting seekers to experiment with and dabble in competing systems. The various systems, be they Christian, Buddhist, Muslim, new age, or otherwise, are now “open source,” to use the parlance of computer programmers.

Apple’s Steve Jobs made it a point to read his favorite book, "Autobiography of a Yogi," once a year. The book was written by Indian spiritual guru Paramahansa Yogananda, a man credited with bringing yoga and meditation to the West in the 1920s. The book is filled with a synthetic blend of Hindu and Christian teachings along with stories of miracles and saints. In 2008 Jobs personally telephoned the Self-Realization Foundation, run by Yogananda’s devotees, to request permission to sell "Autobiography of a Yogi" on iTunes. In 2011, the year Jobs passed away, the only book on his iPad for what turned out to be his last family trip to Hawaii was "Autobiography of a Yogi."

For a man who did not finish college and never formally studied computer science or industrial design, Jobs drew many of his inspired ideas from elsewhere. Yogananda was known for teaching Kriya Yoga, a spiritual science for achieving union with God. The science of divine union is rooted in a series of techniques that require intense concentration and promise a profound religious experience. Jobs’ desire to combine the humanities with engineering in his products resonates with the idea that religious experiences are something that can be programmed through technique. It fulfills the insight of Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, who said, “When a religious method recommends itself as ‘scientific,’ it can be certain of its public in the West.” The inverse may also be true. The marriage of physics and metaphysics in the Apple rhetoric is symptomatic of the enduring relationship between a culture’s crowning technological achievements and questions of ultimate concern.

From the book "Appletopia" by Brett T. Robinson. Copyright © 2013 by Baylor University Press. Reprinted by arrangement with Baylor University Press. All rights reserved.

Shares