Attorney General Eric Holder is expected to announce today a plan to circumvent statutory mandatory minimum sentences for drug possession crimes, taking an important step in curbing a policy that has long been viewed as draconian, unfair to minorities, too costly for taxpayers and harmful to the economy. It comes on the heels of a move by California voters to repeal the state's strict "three strikes" policy, largely over concerns about prison overcrowding.

But as mandatory minimums may be on their way out, it's worth remembering how the laws -- which require judges to hand out big sentences for even minor crimes -- came in, and the college basketball player whose untimely death from a cocaine overdose in 1986 was exploited by Democrats in a push to install one of the key laws in the country's "war on drugs."

As Eric Sterling, a former counsel to the House Judiciary Committee who participated in the passage of the law, explained to Frontline several years ago, it was Democrats who controlled the majority in Congress and often battled with the Reagan White House, who led the charge:

In 1986, the Democrats in Congress saw a political opportunity to outflank Republicans by "getting tough on drugs" after basketball star Len Bias died of a cocaine overdose. In the 1984 election the Republicans had successfully accused Democrats of being soft on crime. The most important Democratic political leader, House Speaker "Tip" O'Neill, was from Boston, MA. The Boston Celtics had signed Bias. During the July 4 congressional recess, O'Neill's constituents were so consumed with anger and dismay about Bias' death, O'Neill realized how powerful an anti-drug campaign would be.

Sterling, who went on to be president of the Washington-based Criminal Justice Policy Foundation and co-chair of the American Bar Association, explained that O'Neill rushed the bill through because he wanted to get the law finished before the November election. Mandatory minimums had been removed from federal law in 1970 "after extensive and careful consideration," Sterling said, but the political appeal to get tough on drugs was too strong and they forged ahead.

"No experts on the relevant issues, no judges, no one from the Bureau of Prisons, or from any other office in the government, provided advice on the idea before it was rushed through the committee and into law. Only a few comments were received on an informal basis," Sterling told the PBS documentary series.

When the Anti-Drug Abuse Act swept through the House 378-16 in mid-October, Democrats and Republicans claimed victory. The bill won't eradicate the drug problem, Harlem Democrat Charlie Rangel told the Washington Post at the time, but "at least we can go home and tell our constituents that we tried."

Why such the bipartisan fervor? "I think it comes down to one young man not dying in vain," California Republican Rep. Robert Dornan told the Post in September of 1986, referring to Len Bias.

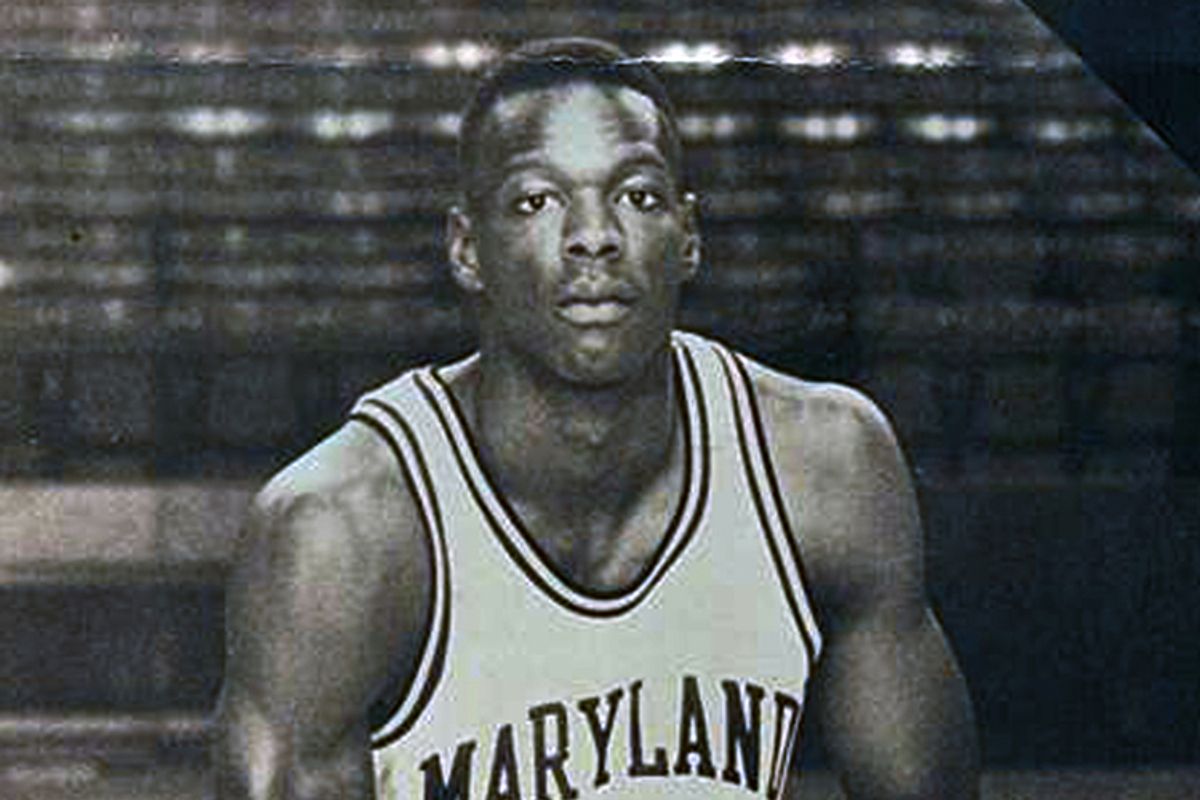

Bias was widely regarded as the best college basketball player in America of his time and considered the best player who never got to play pro. He was mourned in the sports world, eulogized on the cover of Sports Illustrated, and his memory still draws passions to this day.

Boston pollster Thomas Kiley added: "Drugs took off this year, and cocaine use made it take off, affecting more and more people ... Bias and [slain Cleveland Browns player Don] Rogers clinched the deal."

In the press and in the halls of Congress, the law was often referred to as "The Len Bias Law," and still is on occasions. In Oregon, U.S. Attorney Kathleen Bickers has pioneered a tactic of using the law against drug cartels and kingpins by squeezing all those in the supply chain. After someone dies of an overdose, prosecutors threaten anyone who sold drugs to the deceased with a 20-year sentence unless they turn over evidence that leads to the next link up the chain. According to the Oregonian, Bickers was the first to use this approach in 2004, and the state has "40 Len Bias prosecutions since."

How Bias would feel about being the catalyst for the Reagan buildup in the war on drugs we'll never know. Most of his family doesn't talk about it either, except for his mother, who has plenty to say.

Shares