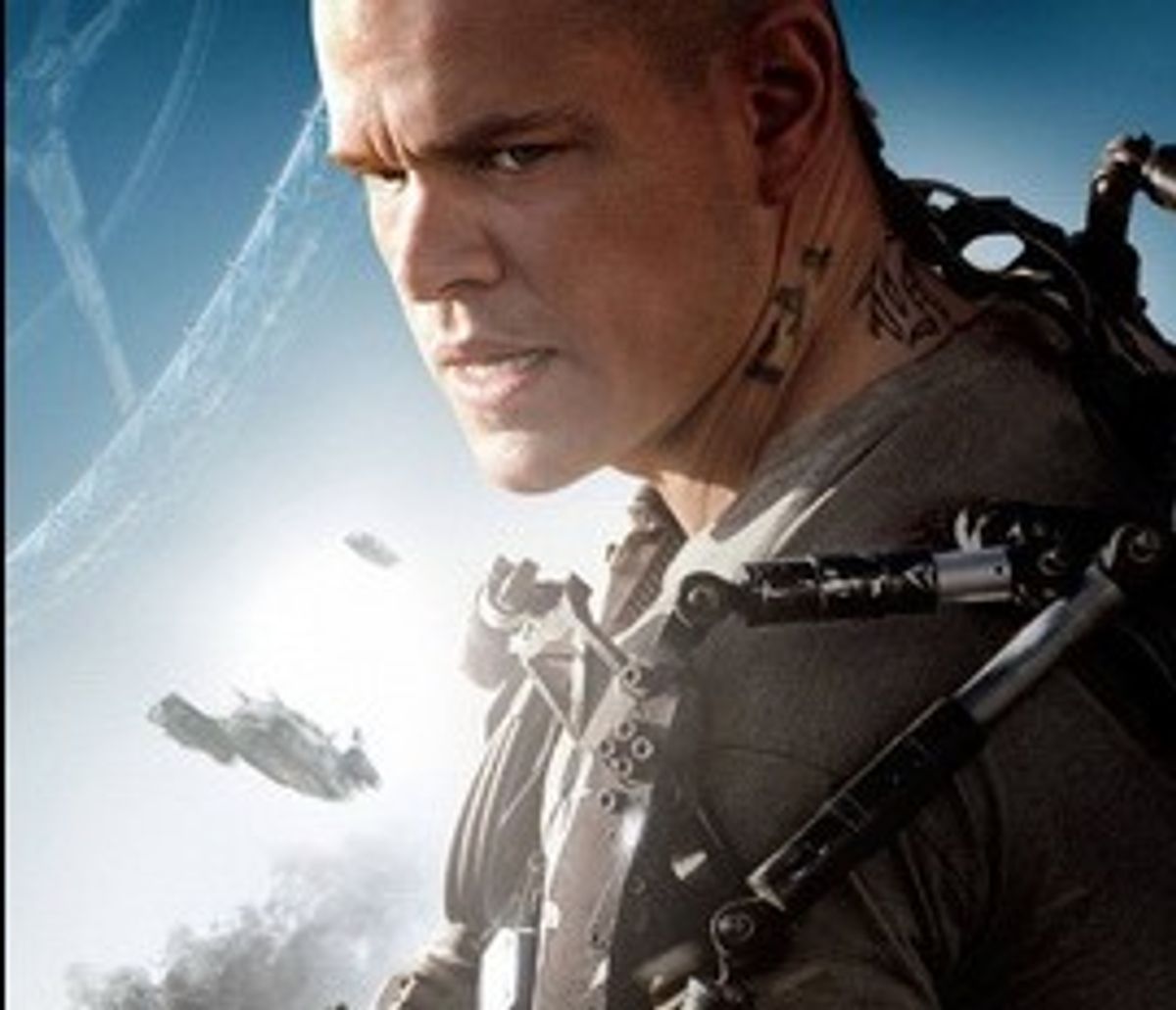

Trailers for Elysium were like catnip for the left-leaning viewer: a near future where the masses, stranded in crumbling cities, outfit Matt Damon with a robot suit and send him to fight the bourgeoisie, who have Galted off the planet to Space Station Elysium, taking their shrubbery, Spanish-style mansions and cancer cures with them. It promised to be an allegory about class struggle as transparent as director Neill Blomkamp’s first movie, District 9, was about racial apartheid. The 99-vs-1 narrative would finally get the sci-fi blockbuster treatment it richly deserved.

I regret to report that the final result is more decidedly mixed. It’s too bad, because Blomkamp is a director with a lot of talents. For a special effects guy, he retains an appealingly corporeal visual style. Bodies splatter in short sudden bursts of meat; parts of a crashed shuttle twist and dangle like one of Wiley E. Coyote’s exploded contraptions. It’s miles away from the video-game-slick CGI and melodramatic slow-mo of your typical action movie product, with the ridiculous sturm-and-drang attached to every punch and explosion. Blomkamp’s vision of technology-enabled violence contains as much absurdity as it does tragedy. He shares this rubbery viscerality with his mentor Peter Jackson, and it’s a welcome respite from the smoothly functional technofascist superhero space operas that make up mainstream sci-fi.

Blomkamp also has a refreshingly straightforward take on race, no doubt tied to his South African upbringing. It’s a lot harder to talk about the “complexities” of race and class, like the mainstream media likes to do in the States, when you were born in a country where only the white tenth of the population could vote or hold office. Class, of course, remains incredibly tied to race, connected to all manner of material privileges (including not getting gunned down by cops and vigilantes). That the oppressed classes stuck on polluted and underdeveloped Earth are almost entirely brown and black, while Elysium is full of WASPs, strikes me as a bit of political courage that rejects any lingering vestiges of the “post-racial America” trop.

That courage fails when it comes to the casting — Matt Damon was so wrong for this role that I wondered if the studios forced Blomkamp to hire a “bankable” white lead. He couldn’t be that stupid to turn pointed commentary on race, citizenship, and gentrification into a white saviour narrative. Would getting a Latino — or Latina — to lead the rebellion court too much paranoid right-wing backlash? I just don’t get it. In any case, even with his buzz cut and neck tattoos, Damon doesn’t convince as a rebellious guy with a criminal past.

Nor do I understand the gender politics of this film, which can only be described as abysmal. It’s 2013, and the film’s set in 2154, but we never once see a woman fire a gun, throw a punch, drive a car, work in a factory, or even drop an f-bomb. Instead, of the two women actors with any lines, one spends the movie cradling a child in a (pink) nurse’s uniform, and the other is Jodie Foster’s emotionally barren defense secretary. A damsel in distress and an ice queen with a bob cut — not exactly great representation for the women of the future. At the level of representing oppressed groups, Elysium looks like Gone With the Wind compared to The Fast and the Furious series.

It’s a shame, because Blomkamp once again has an excellent concept to work with. The space station concept nicely dramatizes the spatialization of class that geographers like David Harvey and the late Neil Smith have written about for years. Elysium collapses the gated city and the militarized border into one potent metaphor, and Blomkamp’s not afraid to show the privileged defending their picturesque suburbs against crippled children with deadly force. Perhaps the most novel idea is to collapse citizenship with health care. A ticket to Elysium grants you citizenship and access to miraculous life-preserving technologies, a powerful point as citizenship is one of the biggest holes in the Swiss cheese that is Obamacare. Blomkamp’s able to see how the overt authoritarianism of apartheid biopolitics (where blacks were denied citizenship, had their movement strictly controlled and had a life expectancy at least a decade shorter than whites) hasn’t been abolished. Instead, it’s been globalized, covered with a thin neoliberal veneer of market and meritocracy. In Elysium the struggle is not for the means of production, but the means of reproduction, as the vast majority of Earth is treated as a surplus population left to die lest they waste precious resources.

The future’s ruling class withdraws from practically all contact with their inferiors, scarcely able to tolerate breathing the same air. Robots replace the police force that disciplines the Earthlings, as well as the servant class, whose proximity has been a source of perpetual anxiety for the rich for centuries. They’ve even managed to automate affective labor — Damon’s tin-can parole officer (more than a little reminiscent of Johnny Cab from Total Recall) can detect his sarcasm, and offers mood-altering pills in response. So it’s a bit curious that Damon works at a robot-building factory filled with hundreds of human workers — they’ve already replaced a lot these workers with machines, haven’t they? Though it does provide a clever flip on that famous line from the Manifesto: here it’s the working class who produces its own grave-diggers in the form of robot soldiers.

There’s a lot of stuff about hacking and coups that also doesn’t really make much sense — not the biggest problem, really, this is just the MacGuffin for a film about class struggle. But that’s also where the film goes off its own nicely set-up rails: Blomkamp more or less abandons everything that made his set-up so interesting, opting instead for a more traditional action movie spectacle of shootouts, sword-fights, and yes, damsel-saving as the coup plot goes awry. The class struggle narrative takes a backseat to Damon’s ongoing battle with a posse of unstable South African mercs tasked with hunting him down, and who end up turning on Elysium too, for some obscure reason.

I wasn’t entirely sure what the point was here, some sloppy liberal truism about the dangers of black-ops, how they come back to bite you in the ass? Making Foster’s character run the mercs behind the president’s back was a bit of dirty pool as well, letting the Elysium political establishment off the hook for its worst atrocities. It’s perhaps the most sinister ideological move of the film — after all, today’s war crimes are committed, not by power-hungry rogue elements within the government, but by the democratically elected officials themselves. A lot of them even brag about it!

Blomkamp’s got some growing up to do: he’s really more interested in cool futuristic weapons and what they do to bodies than he is in how people really think and act, and what kind of politics would emerge from that. There’s a dearth of jokes in this flick (though I got some hearty guffaws watching a ship ram through a space McMansion), and a real lack of charisma from any character. A class war movie worth its salt should have had much bigger reactions from the audience; my theater was pretty much silent except when someone got chewed up by a rail gun. Worst of all, Blomkamp goes for hyper-edited punch-ups instead of continuing to flesh out his futuristic universe. It undercuts the pleasures and politics of dystopian science fiction: imagining all the contours of a future world, taking current-day trajectories to possible ends, and thus evaluating the present by the future we are likely creating.

With the evacuation of the film’s most interesting ideas midway through, I was ready for a disappointing conclusion. Since Blomkamp failed to sketch out the level of automation in Elysium’s technocratic government, the resolution comes off as too pat. By merely changing ILLEGAL to LEGAL in the code, voila!: universal citizenship! Even the president himself is powerless to stop the robot ships from carrying medical aid down to Earth. Marx said that the improvement of technology would be a necessary condition of transitioning out of capitalism, but I don’t think he ever thought achieving communism would be quite as simple as flipping a switch. Since all we need is Matt Damon with an exoskeleton doing a bit of rock-em-sock-em robots in defense of his lady, Blomkamp’s seriously curtailed the politics of his film.

But this is a larger failure, the failure of a kind of progressive-leaning bourgeois politics of class sympathy. It’s a perspective that is very alive to class, but a politics largely deaf to it. Liberal politics tells you we can solve the contradictions of capitalism simply by figuring out a way to include more people in the wealth that’s been generated. The main problems are moral (greedy mean people!) and distributional (which might explain why Blomkamp smuggles in some Malthusian themes of “overpopulation”).

Radicals know it’s going to take much more fundamental restructuring of society, one which will require prolonged struggle ending with the defeat of the rulers. I welcome a popular culture containing more radical themes, but, in the final account, this is not the class struggle movie we are looking for.

Read more Jacobin here.

Shares