If America’s bipartisan establishment is agreed on something, you can be pretty sure it will be a disaster. That is my reluctant conclusion, after nearly three decades of involvement in politics and journalism, in Washington and New York.

I say “reluctant” because I am not a populist by temperament. I respect academic training as well as expertise based on personal experience. I think that institutions are, or should be, less likely to make mistakes than individuals. I detest people who pose as “contrarians” for the sake of controversy. I would happily be an establishmentarian, if there were a U.S. establishment worth belonging to.

But the track record of what passes for the bipartisan elite in the U.S. in the last generation has been pretty poor. Instead of sober, dispassionate analysis of long-run trends, considered from the perspective of the nonpartisan national interest, the conventional wisdom among America’s movers and shakers has consisted of one hysterical fad after another.

The earliest I remember is the “energy crisis.” In the aftermath of the 1973 Arab oil embargo, it was the conventional wisdom that fossil fuel supplies were about to run out and that we faced a future of energy starvation. Then oil prices dropped in the 1980s, because of new energy finds and efficiency.

Around the same time, back in the 1970s, the consensus exaggerated Soviet power. The Soviet invasion of Afghanistan — a desperate, defensive attempt to stem a wave of Islamist revolutions in Soviet central Asian republics — was portrayed by the right’s alarmists as part of a grand pincer movement around Africa or the Indian Ocean or whatever that could lead to Soviet world domination. A group called “Team B” — including many of the neoconservative foreign policy apparatchiks who would later work for George W. Bush — claimed that the CIA was underestimating Soviet power. After the Soviet Union disintegrated, it turned out that the CIA had actually underestimated the strain imposed on the Soviet economy by Soviet military spending.

Then a few years after the Berlin Wall fell, many of the same neoconservatives who claimed that the U.S. was on the verge of defeat by the Soviet Union proclaimed a “unipolar world” in which the U.S. was a “hyperpower.” America is on the verge of collapse! America is on the verge of permanent global dominion! Whatever.

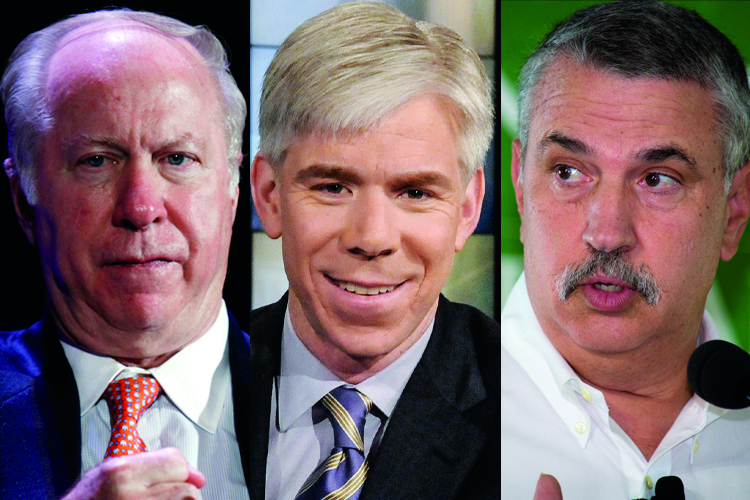

Following the end of the Cold War, the neocon America-as-world-empire narrative had to contend with the neoliberal globalization narrative, identified chiefly with Thomas Friedman of the New York Times. According to globalization theorists, a free global market would soon sweep away all barriers to the free movement of goods, money and people across borders. Nation-states would be replaced by corporations, or maybe virtual countries composed of digital ones and zeroes.

The globalist millennium lasted only a couple of years. In 2008 the post-Cold War global bubble economy collapsed, creating the greatest global slump since the Depression of the 1930s. Countries that refused to liberalize their financial systems, like China and Indonesia, were spared much of the damage inflicted on other countries that foolishly listened to the “Washington consensus” in favor of global financial deregulation. Countries that practice relatively free trade, like the U.S., have been partly deindustrialized by currency-rigging, market-protecting, industry-promoting countries like Japan, Inc., and China, Inc.

Another in the series of conventional-wisdom bubbles was the terrorism panic that followed the al-Qaida attacks of 9/11. Jihadist terrorism is a serious but hardly existential threat. But that was not enough for the alarmists, who, like the neocons Eliot Cohen and Norman Podhoretz, inflated terrorism to the status of “World War IV.” The Bush administration used Osama bin Laden’s atrocities to justify the invasion of Saddam Hussein’s Iraq, which had nothing to do with jihadism. Whether out of opportunism or conviction, the neocons were joined by many “humanitarian hawks” in the Democratic Party who provided bipartisan cover for the disastrous U.S. invasion and occupation of Iraq.

The most recent bubble among the bipartisan elite has been the austerity consensus. Only a year or so ago, most establishment pundits and politicians were assuring us that the federal deficit was so bad that we had to slash Social Security and Medicare. Even President Obama proposed using inflation to erode Social Security for seniors.

Never mind that the temporary expansion of the deficit in the aftermath of the 2008 financial collapse was part of the cure, not part of the disease. Governments need to expand deficit spending to compensate for the collapse of consumer demand and business investment following financial crises. And never mind that the long-term funding problems of Social Security and Medicare are unrelated to the deficits caused by the Great Recession. The conventional wisdom, amplified by Pete Peterson’s millions and minions, held that the long-term deficit, not short-term unemployment or a weak recovery, was the greatest threat to the future. This particular elite fad helped to justify the disastrous sequester, which by contracting demand in the economy further has worsened an already weak recovery.

Most of these elite fads share some features in common. They usually involve the exaggeration of a real but limited phenomenon — greater Soviet aggressiveness following the U.S. defeat in Indochina, the real but limited jihadist terrorist threat, the important but limited benefits to the liberalization of global trade and finance after the Cold War. In other cases, they underestimate public resistance to elite priorities.

The politicians and pundits who get the most attention — at least for a while — are those who treat a genuine but limited and reversible trend as evidence of imminent utopia or approaching apocalypse. Such hype is then magnified by an infotainment industry that promotes drama and penalizes nuance.

I report this with regret, not relish. From the Byzantine era until the Enlightenment, the Venetian republic survived through centuries of war and social upheaval, thanks to the cunning of its senatorial oligarchy, which combined a deep sense of civic patriotism with first-rate intelligence-gathering and a long institutional memory. But the leadership of the Serene Republic of Venice was quite different from today’s American establishment, in which attention-grabbing peddlers of trends and fads who target audiences of the rich and powerful rise to the top at Davos and Aspen, if only until the next fashion comes along.

At the moment, fortunately, we are between ill-conceived elite fads in the U.S. But fashion abhors a vacuum. If experience is any guide, some new Big Idea that is at once fresh, seductive and wrong will soon emerge to excite the political class and the commentariat and become what every serious, respectable person believes — at least until it goes horribly wrong.

When it comes to the hype market, you will seldom err by betting against it. When everybody who is anybody in politics and the press agrees on something, it’s time to raise some doubts.