My son was at his mom's house and his phone was dead. So I posted a question to his wall on Facebook: "We have a chance to review the new Lego Mindstorms robotics kit. Are you interested?"

Eli's reply, seconds later: "Need you even ask?"

Not really, no. My son and I have been playing with Lego since he had enough hand-eye coordination to snap two pieces together. We've been to Legoland twice. I paid for him to attend a not-inexpensive Lego Mindstorms summer camp four years ago. Almost 16 years old now, he told me in July that he was interested in an engineering career focused on robotics. So yeah, I knew what the answer would be. Let's build some programmable robots, Dad! Woohoo!

What I didn't realize was that there would be a bittersweet aftertaste to the awesomeness of geeking out over Lego Mindstorms EV3. Helping him assemble the coolest snake robot we'd ever built (or, to be more accurate, watching him assemble that robot) dragged me back into the past more than it thrilled me on the state-of-the-art robot future. Lego Mindstorms is just a year younger than Eli. It is advancing in fearsome capability as remorselessly as Moore's Law. But my son is growing up even faster.

EV3 is the third major iteration in the Mindstorms family tree. Naturally, it boasts more processing power and computer memory than its predecessors. The programmable "brick" that is the heart and brain of every Mindstorms robot even comes preloaded with a Linux operating system. The infrared sensor kicks ass. The color sensor can detect seven different colors. The motors can lift mountains (of Lego). There are apps that will let you access building instructions from your iPad or phone. EV3 is backward compatible with Mindstorms NXT, and arrives preloaded with 594 Lego Technic pieces that can be configured in a bewildering infinity of ways. By virtually any measure, it is an impressive piece of entertainment/education technology. There isn't a Lego geek on the planet who wouldn't be thrilled to explore its mysteries.

But all that power comes with a hefty price tag: EV3's suggested list price is $349. So be forewarned. Mindstorms isn't a toy. It's a commitment. A way of life, even.

* * *

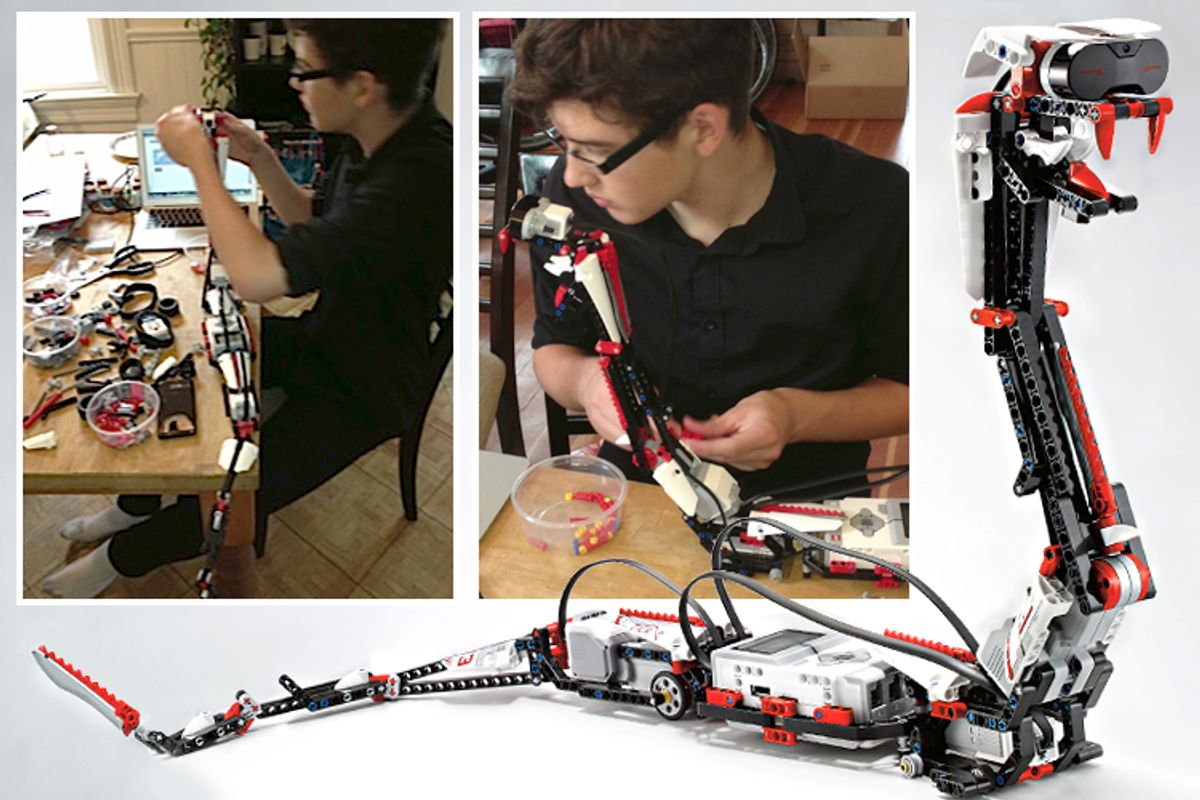

I'm watching Eli put together the "Reptar" snake robot -- one of five robot models whose building and programming instructions are included in EV3's software. (Another 12 models created by members of the Mindstorms "community" will be available Sept. 1.)

I am marveling at Eli's speed, precision and organization. The boy has skills. His first step was to re-sort all the pieces into plastic containers for easy access, a logistical maneuver that saves gobs of time. He needs no more than a glance at the instructions to grok them completely. His long, slender fingers move with the confidence of a master pianist or jewelmaker. He is in his element.

I am suddenly out of mine. I feel like a fifth wheel, or even worse, like a big old Duplo block, rendered obsolete by the passage of time. He doesn't need me. In fact, I kind of feel like I’m in the way. My daughter is already in college, which sometimes feels like another planet. My own irrelevance to the Mindstorms process is the latest proof that my son is starting to slip away. That wasn't supposed to be the point of this exercise.

When Eli and I assembled our first Lego kits together, he could neither read nor write nor understand the first thing about how to interpret building instructions. His stubby little fingers had trouble manipulating the smaller parts. I can remember grasping his hands in my own, guiding his fingers through the ur-Lego moment -- the satisfying snap together of precision-molded plastic.

Those days are long behind us. The boy sitting at the table is now taller than me. His giggle has deepened into a chortle. He enjoyed Joss Whedon's "Much Ado About Nothing" more than Guillermo del Toro's "Pacific Rim." His peer group trumps his parents. The idea of a father-son geek-out is attractive to both of us in the abstract, but the reality is that I am twiddling my thumbs while he moves at lightning speed.

Which is not to say I am utterly useless. There were a couple of false starts. The first EV3 review set was missing an entire plastic bag worth of crucial pieces. A replacement set was immediately shipped to us, but not long after my son started delving into it, I heard an anguished cry. One of the motors turned out to be slightly deformed, so as to make it partially dysfunctional. Eli's dismay is tangible. Irritated, I stare at the motor for a few seconds. Then: Eureka! I hadn't yet returned the first review set! We swapped out the bad motor for a pristine one from the other set. The day was saved.

Does this display of advanced problem-solving skills signal that the old man's still got game? I hope so -- there are few things I enjoy more than slicing through a Gordian knot befuddling either of my spawn. But each time it happens, it feels like a longer period of time has elapsed since the last success. Good parenting means raising your kids to solve their own problems. Great. But then what do you with yourself?

Answer: You go make dinner while your son finishes off the snake robot. While slicing garlic, you keep an eye on his delightfully furrowed brow. It will do.

* * *

Eli was not even 1 year old when a review copy of the first Mindstorms kit arrived at the offices of Salon in the fall of 1998. My colleague Janelle Brown entertained everyone in the office with "Oscar," a robot that would reverse motion after smacking into walls -- and then, more often than not, collapse into a pile of Lego rubble. As Janelle acknowledged in her review, her Lego skills were rusty.

As a technology reporter, a geek and a Lego fan from earliest memory, I lusted after that Mindstorms kit. Mindstorms offered a perfect snapped-together metaphor for all the promise and potential of the first bold rush of Internet-and-computer social transformation. Mindstorms was the vanguard of a glorious future.

But Eli wasn't anywhere near ready. He could barely talk! I had to grit my teeth and be patient. It was hard. I wanted the future to get here already. What great things we would build!

It would not be an exaggeration to suggest that I launched Eli on an accelerated program of Lego study and research so as to justify eventually purchasing a Mindstorms robotics kit that I really wanted to play with for my own selfish purposes. Yeah? So what! This is what we do to our children. It's no accident that the boy likes science fiction movies, fantasy novels, Japanese anime and robot kits. I raised him to satisfy my own longings, just like I raised my daughter to have someone to rage about politics with while eating breakfast.

My strategy worked. Eli is a quick learner. He soon figured out how to parse building instruction drawings on his own. My role evolved with starling speed. I was the piece-finder and problem debugger. (Not to mention primary funder.)

By the time he was 7 or 8 he didn't need much assistance with traditional Lego kits -- and certainly not with his own creations. By then I was mostly reduced to delivering hoots of appreciating, ready to ooh and ah at whatever crazy thing Eli designed on his own from the dozens and dozens of kits whose pieces were now all mixed together in huge crates. He had a housemate a few years older than him at his mom's house who was also crazy for Lego. They built wondrous things. I would see them when I picked him up to bring him back to my house. I always felt a little jealous, but what can we do, but admire well-executed programming?

Mindstorms was my secret weapon, my way of keeping ahead of the curve, of giving him something he couldn't get anywhere else. By the time he was 9, I figured he was ready. I got him Mindstorms NXT for his birthday.

I had multiple agendas. Working robots are their own reward, of course. But I also had this dream of learning how to become a better programmer with Eli as my partner in crime. The earliest versions of Mindstorms' programming language were pretty clunky, but with each iteration the sophistication has improved. EV3 is no exception to this rule: It is easy to start programming, and yet there is no practical limit to the complexity that you can achieve, just by dragging and dropping different icons onto your "programming canvas" and tweaking their variables.

But my vision didn't quite pan out. While his building skills were superb, 9-year-old Eli didn't have the patience to try to puzzle out more complex programming challenges. And to be honest, neither did I. Maybe I lack a certain capability for abstract thought, or maybe I'm just lazy. But there appear to be good reasons for why I'm a writer, and not a software developer.

To this day I feel like I let Eli down. A true geek Dad would have encouraged his children to write Perl scripts in elementary school and graduated them to Ruby on Rails by eighth grade. The coolest programming learning environment imaginable was scattered over the floor of his bedroom, but we ended up skating over the hard parts. If Eli really wants to be a robotics engineer, he's going to have to learn how to code. But at this point, what he learns is up to him.

There is a drawback to returning to mining the same veins of ore that gave you so much pleasure when you and your children were younger. You remember not only the fun you had, but the dreams you failed to realize.

* * *

I've hardly made any progress with getting dinner on the table before Eli has completed Reptar's assembly. Visually, the snake is stunning, a reticulated slitherer that looks like it arrived in our living room fresh from convincing a maiden to eat a dangerous apple. Eli marvels at the creativity of the people who are paid to design Lego's models. "That's a great job," he says, wistfully.

He creates a test program, downloads it via USB from my MacBook Air to Reptar. He hits "run."

Reptar blows us away. The infrared sensor built into its startlingly lifelike cobra senses anything that gets within a few inches and signals for a devastating strike. It is both scary and hilarious. Eli brings his phone up close and shoots video. Reptar treats him like a particularly obnoxious species of paparazzi, lashing out with its plastic fangs again and again.

We are laughing. Even Tiana, the 18-year-old, is impressed. Mindstorms EV3 has delivered. This is high-quality Lego action.

Eli looks at me. "Whyyyyy can't we keep it, Dad?"

Are those puppy-dog eyes I see? Where did this 10-year-old suddenly come from?

Eli knows the answer. He knows that this review copy must be returned in a couple of weeks. And I know too that his longing is more virtual than real. Carving out time in his busy life just to build this robot took some finagling. He's got friends to see, games to play, girlfriends to text. If I plunked down $349 for a new Mindstorms kit, chances are he'd mess around with it for couple of weeks and then move on to other obsessions.

But I treasure this moment of nakedness. His normal armor of sophistication and sarcasm has crumbled, replaced by open rapture. In his plea, I recognize the boy that got me to buy him a Millennium Falcon kit at Legoland, the boy with whom I have made countless Japanese Gundam giant-robot kits, the boy who will forever respect me for having turned him on to "Fullmetal Alchemist" and "The Song of Ice and Fire."

In that question, I hear echoes of the boy who giggled delightedly on his fourth birthday when he was whacking away at the piñata I had bought for his party because it was it was in the shape of, you guessed it, a robot.

In that question, I hear the sound of boyhood, of endless summer days and make-believe and adventure. And I hear the promise of our favorite sci-fi future, in which the robots always get cooler and there are no limits to what we can create.

I hear a sound that I want to bottle up and keep forever. A sound that makes $349 sound cheap.

* * *

A couple of days later, Eli is out of town, on vacation with his mother. I feel a responsibility to my EV3 "review" to get some hands-on experience with the kit, so I spend an afternoon putting together the flagship robot model included in the kit "Everstorm." It's an impressive piece of work, with tanklike treads for motion, infrared eyes, a touch sensor on its shoulder, capable of launching bazooka shells from its left arm.

I fumble about a lot more than Eli did. I make mistakes, and have to retrace my steps. I am intimidated by the programming interface. I try to find the boy within me, the kid who spent his afternoons and weekends gluing balsawood together and building plastic battleships and making mansions out of Lego. But he's damn hard to find. I'm worried about deadlines, home repairs, packing for my own vacation. I have a hard time getting in the flow.

I realize that I'd rather watch my son build a robot than put one together myself. He might not need my help, but I need to see his attention captured, his fingers flying across the harp strings. It will be but a moment before he trundles off to college like his sister. I'm not looking forward to the day when all his joys and sorrow, his dismays and exaltations, are filtered to me through text messages on his phone and Facebook posts.

I am sad. But it's OK. I must have done something right. Huh. He wants to be an engineer specializing in robotics. Who would have figured?

Shares