Girlboys may nothing more than boygirls need.

— e. e. cummings

“When did the desire to be female first occur?” I ask Chevey. We are talking on the phone in March of 2006. He has come home from an extremely painful bout of electrolysis on the West Coast, and will go to San Francisco in April for the facial feminization surgery.

“I’ve thought about that question many times. It was at Ashley, when we lived in the country. I distinctly remember going up into your room, which was along the hall and up the steps in the old part of the house, and trying on your clothes when no one was around. I’ve since tried to go back and figure out how old I was at that time, but I don’t have a frame of reference. I guess about six or seven years old. We lived there till I was ten. So that’s all I have to go by.

“I do remember times when Mother would say things, not realizing what she was saying. Like one time she mentioned this silly thing, how if you could kiss your elbow it would turn you into a girl. And though on the surface I ignored it, inside I jumped. I know it was idiotic but I must have just about broken my arms a couple of times after that, trying to hold my arm in a door, to see if you could get to your elbow. But of course, you can’t.

“I didn’t have, we didn’t have, the concept of ‘transsexual.’

“It probably wasn’t long after I started dressing up that Christine Jorgensen hit the news. [This would have been 1953, when Chevey was seven.] I happened to be in the room when Mother and Daddy were talking about the news. Most dismissed it. It was a once-in-a-lifetime thing; she was seen as a freak, not as big a deal as Renée Richards was years later. But I must have at least known I didn’t want to get caught dressing up; I had the concept of ‘sissy.’”

In fact, Christine Jorgensen (1927–1989), the Brooklyn-born professional photographer and ex-G.I., who went to Denmark for surgery in 1952, was not the first but the most world-renowned transsexual. In around 1930 or ’31, there were two in Germany, the most famous of whom was a Danish painter named Lili Elbe (né Einar Wegener). Her tragic story (recorded in the book "Man into Woman") involved a series of experimental surgeries, including the implantation of ovaries, and after only a year, she died. But it was Jorgensen who entered the public spotlight and became a catalyst for other would-be transsexuals, many of whom went to Europe for surgery. She also became a patient of Dr. Harry Benjamin, the German endocrinologist turned sex researcher.

“When I look back,” Chevey continues, “I’m surprised and amazed at how my life and my very, very slow transition to being female almost coincides with society’s realization of transsexualism — I won’t say getting used to it, but just hearing about it more and more. It’s actually an incredible leap, from the dark ages of the fifties and sixties to the present-day explosion of stories in the papers and on television.

“It was Renée Richards who really turned my life upside down. Christine Jorgensen seemed remote — we wondered if this was truth or fiction. But when Renée Richards appeared on magazine covers in 1976, playing women’s tennis, and we learned that she had been an ophthalmologist named Richard Raskind . . . well, that just blew the

lid off. Before, I think my feelings of being a boy were stronger than of being a girl, simply because that’s all there was.”

I agree. There has to be a possibility, an example, even a descriptive language, before such vague feelings and disturbances can coalesce into a concrete “something,” a condition, a visual image, a real-life possibility.

The scandal caused by this pivotal event may be hard to remember now. Born in 1933, educated at Harvard, an enlistee in the Navy, ranked male tennis player, this handsome, even beautiful, man became a woman at age forty-one. When she tried to play professional tennis as a woman, she was ostracized by her fellow players, rejected by the crowds, and lampooned in the media— Bob Hope joked with Johnny Carson on "The Tonight Show" that she was her own “mixed doubles team.”

Nevertheless, for people like my brother, it was as if lightning had struck, illuminating a path but unleashing a storm of agonies as well.

“When that happened, it all came to the surface. I acknowledged to myself my yearning to be female and told Beth, and that caused my castle walls to crumble. Up to then, I hadn’t spent a lot of energy thinking about it, because it simply wasn’t in the realm of possibility. Now it seemed there were others out there, and information, and doctors. It was still experimental, of course, but there were doctors who did this!

“I keep repeating this point, but you can’t imagine what it was like back then, and why Renée Richards was a like bomb going off. At the time, homosexuality was still in the closet; admitting it would destroy your life. I remember a movie about that time ["Advise & Consent," 1962], based on a book, about a congressman who commits suicide rather than be exposed as a homosexual.”

Yes, the world has changed, at least theoretically. The argument against gender-specificity advanced by my students is gaining currency.

Shifting shapes and, in academic-speak, the problematizing of identity represent a retreat from the presumed rigidity of traditional norms: the dominant male and supine female who define each other by their differences. Cutting-edge gender provocateurs like Marjorie Garber and Camille Paglia speak of “the pitfalls of gender assignment” and of our fetishizing gender. The psychoanalyst and author Ken Corbett, in his illuminating "Boyhoods," actually argues that the terms “male” and “female” have outlived their usefulness as designators of gender identity, as have the prescriptive norms tucked within them. Judith Halberstam, celebrator of butch females in her book "Female Masculinity," speaks of a “post-gender world.” The gender-studies expert Anne Fausto-Sterling ("Myths of Gender: Biological Theories About Men and Women"; “The Five Sexes: Why Male and Female Are Not Enough”) has mounted an extensive and scholarly challenge to the rigid division of male and female in Western culture, citing examples of hermaphrodites and other variations in the organization of gender that she insists must be seen as a spectrum.

Real-world hints as to the porousness of the sexes were not unknown. As a teenager, I went each year to the State Fair with my friends and eagerly sought out the “Half Man, Half Woman” exhibition. With a mixture of horror and giddy fascination, we would place ourselves on the children’s side of a curtain that divided us from the adults, who were apparently exposed to the naked body of the hermaphrodite (if that’s what “it” was) while we were shown only the upper half. Who knows how we absorbed the implications of this, but certainly the image was hard to erase.

If male and female, masculine and feminine, have become unreliable opposites, transgender has become even more of a blur. And where there were once no words for it, now they proliferate with a vengeance. Transgender is, itself, a term whose parts are constantly shifting and overlapping.

The simple taxonomy of TGs-meet-yokels road movies such as "To Wong Foo, Thanks for Everything! Julie Newmar," and "The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert" seems almost quaint. "To Wong Foo," which came out in 1995, features Wesley Snipes and Patrick Swayze as prize-winning drag queens, and John Leguizamo as the teary wannabe for whom Snipes lays it out: “When a straight man puts on a dress and gets his sexual kicks, he’s a transvestite. When a man is a woman trapped in a man’s body and has a little operation, he is a transsexual. When a gay man has way too much fashion sense for one gender, he is a drag queen. When a tired little Latin boy puts on a dress, he is simply a boy in a dress.”

If only it were so simple.

There are many and ever-changing variants in the ever-blossoming field of “gender nonconformity,” from biological aberrations like hermaphroditism (a child born with both sets of genitals) to performance celebrations (drag and female impersonators), all of which challenge the feminine-masculine polarity around which we organize our self-image.

Along the transgender spectrum, female-to-male transsexuals have probably been underrecorded (the one-in-five statistic has recently been adjusted to almost equal). For one thing, it’s so much easier for a woman to dress, even act, like a man and pass under the radar than it is for a man to cross-dress without raising eyebrows. For another, the surgery is unsatisfactory (the penis being so much more difficult to create than the vagina). Moreover, female-to-males tend to keep a low profile, withdrawing from the limelight that their counterparts actively seek. The club of “difference,” LGBT, now includes “I” for intersex, a coinage as yet without a definition. The gender rebels constantly invent their own lingo (like “genderqueer”— synonymous with androgynous), rejecting the medical vocabulary that wafts sulfurically from the laboratory and stigmatizes “disorder” with terms like “sexual dysphoria."

It’s the word “sex” that causes the problem, since the first basic and unequivocal rule is that transsexualism is not about sex, sexual behavior, or sexual orientation, but rather about identity: gender identity. Sex is biological and anatomical — chromosomes, genes, anatomy, gonads, hormones, as well as being the locus of one’s carnal desires. Gender on the other hand is how we perceive ourselves: a social construct with culturally determined roles, attributes, emotional responsiveness, a mixture of nature and nurture with one reinforcing the other. Nevertheless, one of the main distinctions and the most important one for our purposes is the difference between transvestism and transsexualism.

A transvestite, or cross-dresser, is a man, most often heterosexual, who occasionally and for purposes of titillation, dresses in women’s clothes, and has no intention of removing his penis. Robert Stoller describes it as a way of indulging in the temptation while avoiding the danger of being “female,” the arousal produced by the act being confirmation of manhood. According to Stoller, the transvestite says to himself, “‘Am I still a male, or did the women succeed in ruining me?’ And the perversion — with its exposed thighs, ladies’ underwear, and coyly covered crotch — answers, ‘No, you are still intact. You are a male. No matter how many feminine clothes you put on, you did not lose that ultimate insignia of your maleness, your penis.’ And the transvestite, or ‘CD,’ gets excited. What can be more reassuringly penile than a full and hearty erection?”

A transsexual (or “T”) wants only to be the opposite sex, and wears that sex’s clothes not for a transvestite’s erotic charge but to feel that she is where he belongs, or he is where she belongs. Sexual orientation will vary and may not be known until after hormones: Jennifer Boylan quotes her own therapist that one-third of male-to-female transsexuals become man-desiring heterosexuals, a third homosexual (i.e., lesbian), and another third asexual. Chevey has said that Ellen [Chevey's female identity] will be in the first category, but I ask him how he knows.

“You can’t know definitively and you always wonder.” (Here, and on other sensitive occasions, I notice my brother retreating from the confessional “I” into the impersonal “you.”) And not having had any sex with a man, you can’t really be sure other than feeling an attraction to them, but you can’t get rid of your attraction to women, either.” He describes attractions that are more romantic-erotic than pointedly sexual — a movie star’s sex appeal is exciting but not necessarily in a genital way. “You don’t want to spread your legs but all of you is attracted to attractive people, on so many levels.”

*

J. Michael Bailey, a psychologist at Northwestern University whose writings about the sexual fantasies of transsexuals provoked a firestorm of controversy (about which more later), made a career studying the behavior, speech, and movement of various transgender types. In his signature book, "The Man Who Would Be Queen," citing the original findings of researcher Ray Blanchard, he describes the differences between homosexual and heterosexual male-to-females, finding the former to be extremely feminine gay men, whereas the heterosexuals were men “erotically obsessed with the image of themselves as women.” He and other researchers pointed out what now seems obvious: that heterosexual male-to-females, as distinct from homosexual transsexuals, are often not very feminine. Or as Chevey says: “There are two types of transsexuals — those who grow up beautiful, with high voices, and pass easily, and other types, like me, who are just the opposite. There’s no way you can hide it.”

And what about recent articles on preschoolers, boys who want to dress as girls and who may or may not ultimately become gay or transsexual. Some of the kids go back and forth, makeup and nail polish one day, rough-and-tumble guy togs the next.

For Chevey, “Dressing up for me wasn’t the same as for a transvestite or a drag queen. Maybe I’m splitting hairs, but it wasn’t a sexual turn-on so much as the only thing you could do that would allow you to experience a little bit of your female side.”

“Did you ever feel you were glad to have a penis, that it was gratifying or superior?”

“Not at all. I was just wishing I could change. And at that time there was no hope. There were no ‘role models’ except through the back door: I’d go to a movie like "Goodbye Charlie" with Debbie Reynolds and "Switch" with Ellen Barkin, or "Victor/Victoria" with Julie Andrews: they could take a taboo subject and by treating it humorously, made it okay. Other people would say what a funny movie and what are we going to do this afternoon, but I would see something like that and just be lit up inside. It was the backdoor approach. That’s probably a good term, because you feel ecstatic but you have to keep it to yourself. You’re sitting around and somebody will mention one of those movies and you have to be careful not to let your reactions show. In the first two cases a male character had died and come back, reincarnated as a woman, as if this is the only way for society, or Hollywood, to address this problem, this fantasy of ‘sex change,’ and pass the censors. For me it was a sort of lifeline! I just wanted to go back and see the movie a thousand times. That was before videocassettes or DVDs. Once they came in, I could rent them. And watch them over and over. You don’t realize the importance of some of these things for transsexuals.”

*

In any case, Chevey doesn’t conform to Stoller’s description of a transsexual boy formed by rearing and learning, who “begins to show his extreme femininity by age two or three, though first signs may appear as early as age one.” To my eyes he was all boy.

At the same time, Chevey insisted, it never felt like a choice.

“Eleanor has said several times, ‘You’ve gotten what you’ve always wanted.’ As if it was some achievement or title or prize. The truth is that I wish transsexuality had never happened to me. From the outside it looks like a selfish act, from the inside, not at all. I had a ‘happy’ life before destroying it all. This has nothing to do with happiness. My life was wonderful just as it was. It’s still wonderful! It’s trite to say it, but I wouldn’t wish transsexuality on my worst enemy. Like everyone born with a birth defect — which I believe transsexuality is — I wonder, ‘Why did this have to happen to me?’ ”

“How did the decision come about?”

“The need is much stronger. Decision is the wrong word. It has taken me many years to understand, trying to keep an open mind about what seemed important at the time, and what has come to seem so in retrospect.

“First, to do such a thing would have been totally self-destructive, emotionally and physically. In the relative tolerance of today, we simply do not remember just how hostile the environment was in 1975. Even twenty years later, they were still dragging gays behind pickup trucks. It would have been impossible. Crazy. The impulse to change one’s sex seems irrational, but to do something about it was even more so.

“Then there was Pete. I didn’t want a child, but had acquiesced, and therefore I took full responsibility. He might or might not have accepted his father becoming a female, but I couldn’t take that chance.

“The reaction of Mother had seemed critical at the time, but I’ve come to think her importance was a lesser factor. After all, I could have just disappeared, gone out to the West Coast with a new name and made a life that wouldn’t have impinged on hers.

“I’d left my marriage, gone out to explore the possibilities, then the survival instinct kicked in. I backed off. As much as I wanted it, I still wanted to live. The determination, the urge and its eventual fulfillment, is not a decision so much as an addiction. So I swore I could control it. But with an addiction, there are things you can do and after a while it gets better. Not this urge. It grows and grows under the surface. You fight the urge, knock it down, it comes back. Over thirty years it takes a huge toll. I began to feel it would kill me if I didn’t go with it. Sometimes I was just shaking, it was so stressful inside. What others call a ‘decision’ was a long, agonizing, soul-searching, gut-wrenching process, and the worst of it was knowing what it would do to everyone around me. I didn’t think I could live with what I’d be doing to others.

“But it gets to the point that it’s suicide if you don’t do it. Whereas earlier, I felt it would be suicide to do it, now it was the reverse. Eleanor never saw the intensity. I hid it from her, so that she didn’t understand; she thought if you can live with it like you’ve done, why can’t you go on? But she had no idea of what was going on inside.”

The idea that it’s a “choice,” at least where Chevey’s concerned, seems increasingly, almost laughingly, difficult to believe when you consider all the disastrous consequences. Here, after all, is what he’s facing: facial reconstructive surgery, the outcome of which no one can foretell; constantly looking over her shoulder for psychopaths so threatened by the idea they’d attack or even kill her; no way of knowing who will stand by her among family and friends; the fear of meeting, whenever she goes out, snickers, murmurs, raised eyebrows, eyes either averted or staring; the overt or subtle ostracism; outrageous expenditures of money for procedures (surgery, electrolysis, hormone patch) with no health coverage. And here’s what he’s giving up: all the advantages of a good marriage, the closeness, the trips, the plans, the sex, the mother-in-law, possibly the stepchildren; the perks of being a man, the automatic authority, the respect of agents, clerks, waiters, his secure place in society.

He expects to be treated like a freak. “My therapist told me about a transsexual patient of his. She went into Starbucks not too long ago, and when she was paying for her coffee, she thanked the guy at the register. ‘You’re welcome, sir!’ he said with heavy emphasis.”

Who would choose this? The cardinal belief among homophobic conservatives that individuals “choose” to be homosexual, with all its disadvantages, is questionable enough, but it would be insane for anyone with a relatively secure and traditional life and lifestyle to throw it all over for a life considered beyond the pale and whose outcome is dubious at best. “Lifestyles,” and identities, in this era of rampant individualism, are not totally without “choice”: we may, and may often, choose which “side” of ourselves to act upon, which to disavow. There’s the minister who chose to suppress rather than express his gay side, as his Christian vocation was more important than his (as he sees it) sex life. Cynthia Nixon angered some in the gay community when she admitted to having been married to a man, then chose to live as a lesbian. For some, it is easier to suppress, or at least marginalize, sex drives than for others. Nixon honestly confronted the heterosexual side that most homosexuals rigorously deny. Even transsexuals deny their former selves, change their birth certificates, but for them, precisely because of the fearful consequences, the word choice seems a misnomer.

“Did you make mistakes,” I ask him, “catch yourself in public thinking I’m a woman and behave differently?

“I didn’t so much think I’m a woman as think I’ve got to act like a man. Later there were times when I’d do something like the gesture I just did — palms open — and I’d catch myself and think, that’s female. A man tends to show the back of his hands; the female is much more submissive. There are little things like that, or maybe you cross your legs in the wrong way and suddenly you realize and correct yourself. You have your antennae up all the time.”

“So you’re a student of female and male behavior.”

“Yes, all my life I looked at women and women’s fashion. I was aware of the way they were dressing. I think back on certain events now, like once coming home from school, or maybe it was cotillion, when I was in an all-girl car pool. The other boys were jeering, and envious. I played it to the hilt; it was cool that I was in the midst of all these cute girls, but at the same time I was thinking — ”

“This is where I belong.”

*

Ethel had suggested we get in touch with gay activist groups or the umbrella organization GLBT (Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, and Transgender) National Help Center, but transsexuals are not really regarded as one of the fold. I mentioned it to my brother on the phone, after he’d gone home.

“They think of us as freaks,” he said, “the same way straight people do.”

How sad was this! I suppose there’s a certain logic: gay males in thrall to the pleasures of the phallus would naturally be the last to identify with such self mutilation. They simply can’t understand it. (In all fairness, who can? Certainly not transsexuals.) Moreover, as political activists, gays have a hard enough time of it without incurring even more culturally dubious fellow travelers. To them, the transsexual is the crazy aunt descending on a family whose social status is none too secure to begin with. In fact, the four components of GLBT are all far more disparate than such a rubric allows for. Gays and lesbians may have less in common than either has with straight people of their respective sexes; and there are subsets and branches of each.

I tried to imagine him, her, somewhere. What about a community with other transsexuals? “I don’t want to be one of them,” he said. What did he even mean by this, a strangely callous remark from someone as generally empathetic as he? I assumed he meant a commune of in-your-face queerish drag queens, mascaraed babes out of La Cage aux Folles rather than sobersided members of society, but why, if they come from backgrounds as diverse as he makes clear they do? He was equally averse to joining an online support group. More of a recluse than a joiner, Chevey had always been obsessed with privacy (the first piece of equipment he bought when he went into business for himself was a shredder). He was so secretive, Mother and I never knew if he had any clients! Even Ethel, when I told her, was surprised at his attitude. “But he is one of them,” she said.

I only gradually came to another interpretation. Because a transsexual thinks constantly and obsessively about being a woman, there’s a tension between the need for support on the one hand, and the desire, if not to pass completely as a woman, at least to live in as utterly normal a way as possible. The last thing they want is to wear the label “T,” join a club, and be seen by the world as freaks or at best hybrids. They’re already so far out on the fringe, so beyond political legitimacy, there isn’t the same desire for political solidarity as among homosexuals or other minorities. Indeed, solidarity would only magnify their problems. Most want, as Chevey says, “to blend in with the heterosexual population.”

This all came home to me when I watched a CNN documentary, "Her Name Was Steven," in which Steve Stanton (now Susan), the one-time city manager of Largo, Florida, gave a lucid and dispassionate account of her feelings and decisions. Of particular interest to me was her appearance at a congress of transsexuals, where she infuriated her fellow transsexuals by refusing to toe the line and voice solidarity.

“Somehow I’ve been thrown into this role as a national spokesperson for a cause I don’t understand myself yet,” she says at one point. Even as one applauds her courage, and sees a woman quite at peace with herself, the ex-wife is a different story. She has refused to appear in the documentary but answers questions off-camera, and at one point says poignantly, “I watched him gradually fade away, and it has been like a slow death for me.” Eleanor must be feeling something like this about Chevey.

I try to imagine losing Andrew in a way that is almost more complete than death, because it brings into question the shared past and the self that has morphed and mutated, but always within the endless dance of marriage.

I ask Beth if Chevey’s revelation of transsexualism undermined her sense of their marriage, and she replies in the negative. They were best friends before and remain so.

“He had such integrity,” she says, “more than anyone I’ve ever known. And so does she. Nevertheless, I hope Ellen doesn’t want to talk about hair and makeup all the time. And I’ve told him he can’t be my friend if he wears frou-frou clothes. You know, over-the-top feminine—plunging necklines and short skirts.” The truth is, we’re all more “masculine” than he is, or rather than the she that he will be.

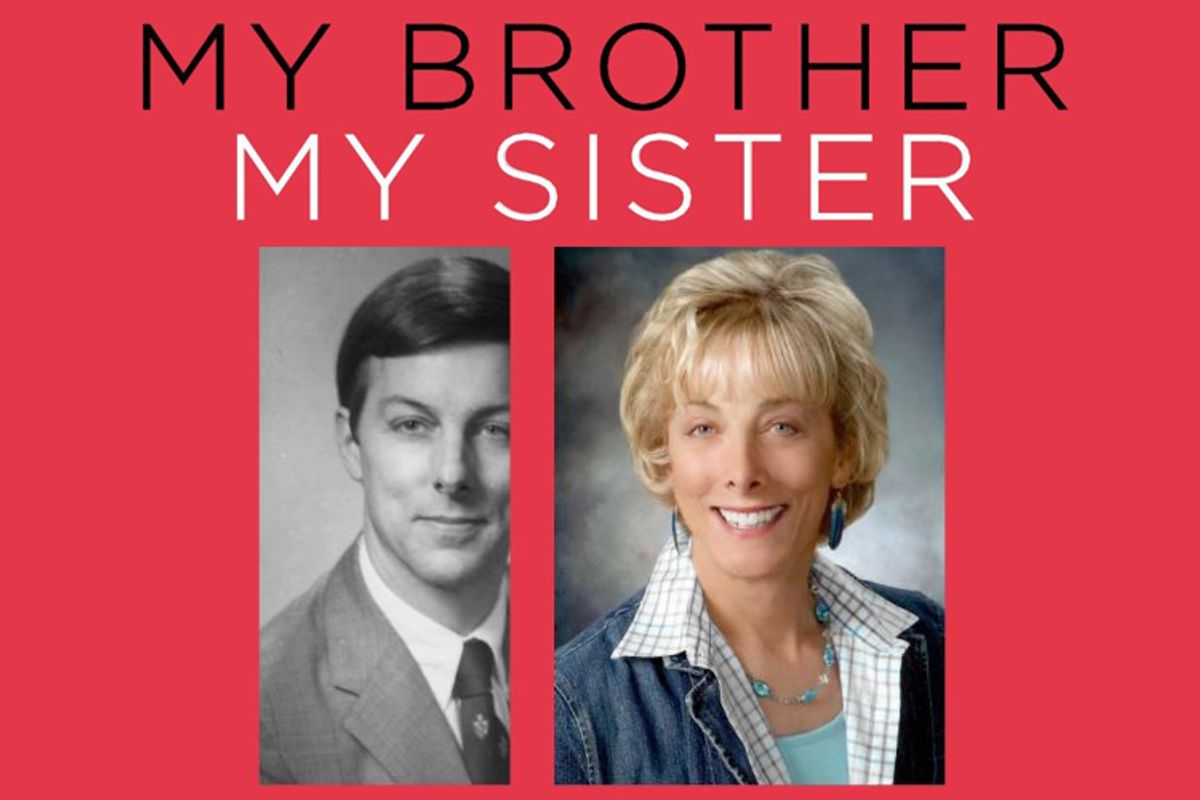

Excerpted with permission from My Brother My Sister: Story of a transformation by Molly Haskell. Copyright 2013 from Viking Adult. All rights reserved.

Shares