Lots of animals reproduce asexually. Why not humans?

This may seem obvious. But in evolutionary terms, the benefits of sexual reproduction are not immediately clear. Male rhinoceros beetles grow huge, unwieldy horns half the length of their body that they use to fight for females. Ribbon-tailed birds of paradise produce outlandish plumage to attract a mate. Darwin was bothered by such traits, since his theory of evolution couldn't completely explain them ("The sight of a feather in a peacock's tail, whenever I gaze at it, makes me feel sick!" he wrote to a friend).

Moreover, sex allows an unrelated, possibly inferior partner to insert half a genome into the next generation. So why is sex nearly universal across animals, plants and fungi? Shouldn't natural selection favor animals that forgo draining displays and genetic roulette and simply clone themselves?

Yes and no. Many animals do clone themselves; certain sea anemones can bud identical twins from the sides of their bodies. Aphids, bees and ants can reproduce asexually. Virgin births sometimes occur among hammerhead sharks, turkeys, boa constrictors and komodo dragons. But nearly all animals engage in sex at some point in their lives. Biologists say that the benefits of sex come from the genetic rearrangements that occur during meiosis, the special cell division that produces eggs and sperm. During meiosis, combinations of the parents' genes are broken up and reconfigured into novel arrangements in the resulting sperm and egg cells, creating new gene combinations that might be advantageous.

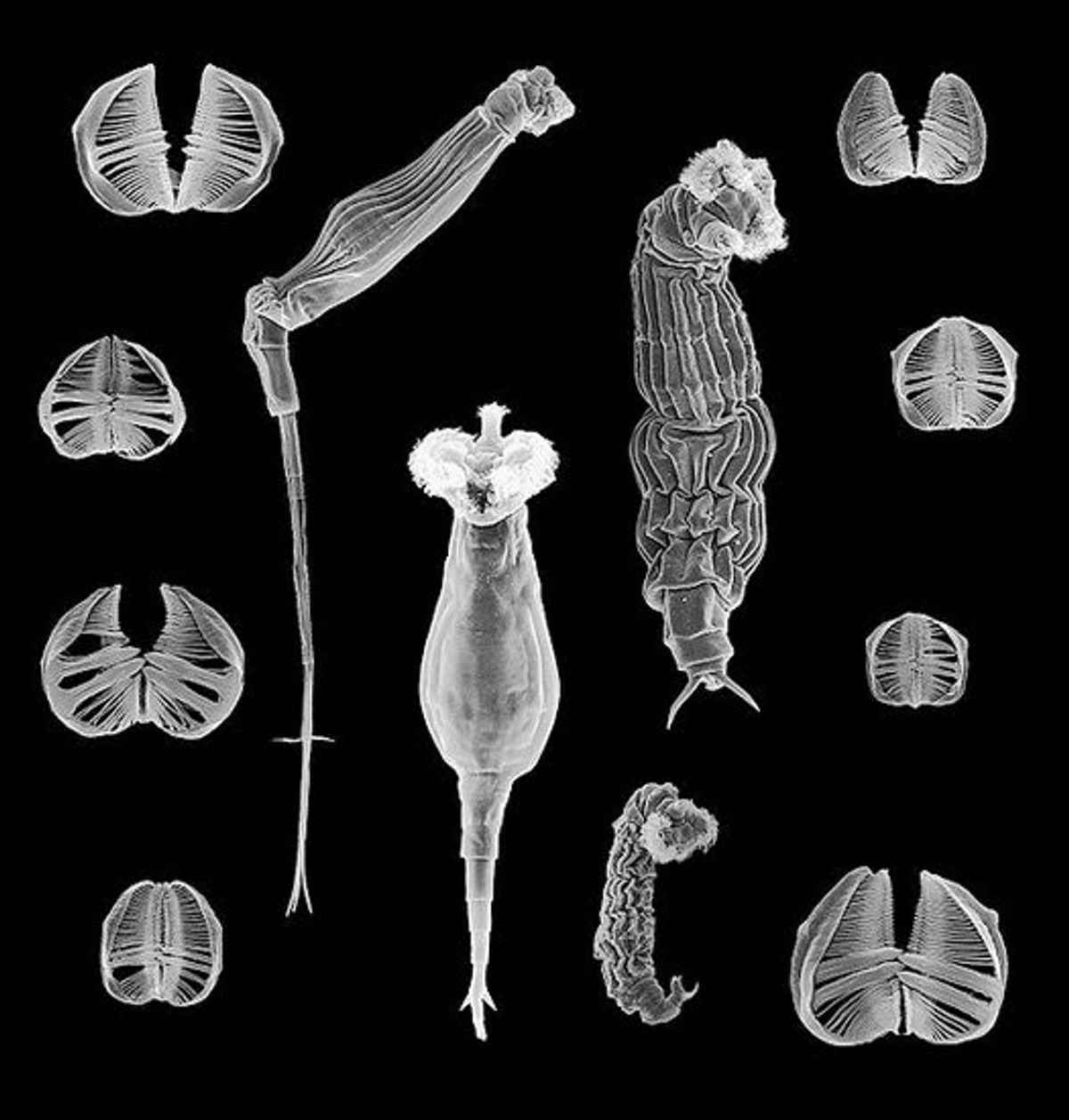

Shouldn't natural selection favor animals that forgo draining displays and genetic roulette and simply clone themselves?One animal, however, has done just fine without any sex at all. Bdelloid rotifers can be found in most freshwater ponds, measure a few tenths of a millimeter long, contain only about 1,000 cells, and have been chaste for roughly 80 million years. The nearly 400 described species of bdelloids prove that the group is respectably diverse, yet no one has ever seen a male. Bdelloids lay unfertilized eggs that grow to be fully fertile daughters. What's the secret?

Harvard University biology professor Matthew Meselson and his lab have spent the past several years investigating bdelloids' molecular genetics. By exposing bdelloids to extremely high levels of ionizing radiation (a treatment that causes hundreds of physical breaks in DNA strands), one of Meselson's former graduate students, Eugene Gladyshev, showed that bdelloids can completely rebuild their genomes-an unprecedented feat among animals.

Recently, Meselson and Gladyshev made an even more amazing discovery: Bdelloids have foreign DNA from bacteria and fungi in their chromosomes, which is a great way to maintain genetic diversity. As for the rest of us, we're stuck with sex.

This article originally appeared in the May 2011 issue of Popular Science magazine.

Shares