Memoirs, especially memoirs about hard childhoods, have somehow gotten a bad rap, but there's still no story quite as universal, in its pain and/or its exhilaration, as the story of growing up against the odds. From "Angela's Ashes" to "The Liar's Club," the complicated emotional footwork required to transcend a disastrous home life while remaining true to who you are and where you came from is the subject of this brand of autobiography. Few memoirists have faced challenges as great as those that confronted M. K. Asante.

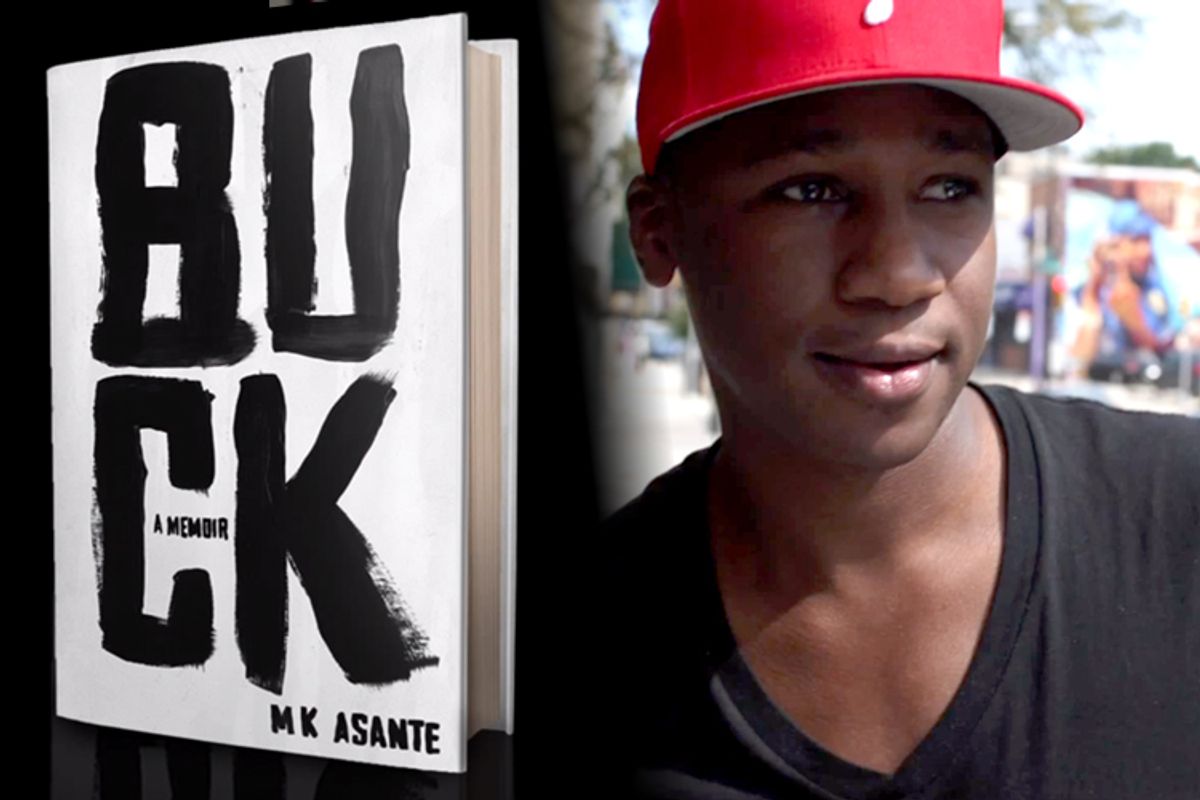

In "Buck," Asante describes coming up in a family that ought to have provided him with precious support. His parents were educated, intelligent people who celebrated their heritage. His father, a college professor known as "the father of Afrocentrism," married his mother, an accomplished dancer, while they were visiting Zimbabwe, where M. K. (who went by the nickname Malo) was born. They'd made it from their own hard childhoods in "projects and plantations" to a Tudor house on a nice block in Philadelphia. But when Malo's older half-brother Daudi (nickname: Uzi) ran afoul of the law, hidden fault lines in the family split open and, at 13, Malo fell through, plunging into a perilous world of drugs, crime and violence.

"Buck" portrays Asante's youth as a tense oscillation between a miserable domestic situation and the hard, jangled romance of the streets. He idolized his big brother, his mother's child from an earlier relationship with an abusive addict, but Uzi and Malo's father don't get along. (Their ur-quarrel was over the racial politics of "Star Wars" action figures; Uzi wanted Luke Skywalker, but his stepfather insisted on Lando Calrissian instead.) Out of a misplaced loyalty to his biological father, Uzi is drawn to the outlaw life. When Uzi finally gets into serious trouble, Malo's father refuses to help: "'He's a thug. You reap what you sow,' he says like a southern preacher."

Malo's mother, on the other hand, is psychologically fragile. (Another sibling, a sister whose mind is clouded with elaborate delusions about their family being descended from European and African aristocracies, has been institutionalized.) She's in and out of mental hospitals and on antidepressants, and eventually Malo's father moves out. Excerpts from her diary are interspersed throughout "Buck;" it takes the form of letters written from Amina, the African name she assumed as an adult, to Carole, the name she was born with.

That detail is one of the most heart-rending in this memoir, a testimony to all the sorrows of a lifetime that can't be soothed with pride and pep talks. "I can't talk to Chaka [Malo's father] unless it's about Afrocentricity or The Movement or telling him I'm getting better," Amina writes to her old self. Her voice offers a mournful counterpoint to the fizzing bravado of Asante's adolescent adventures and street life, and his father's stiff rhetoric is no match for either. At the kernel of this memoir lies the crumpled love of a family that tries and fails to roll with more than its fair share of punches.

Harrassed by a racist principal ("he's got that rare type of limp that, once you meet him, you feel like he deserves") Malo bails on "Foes" -- his name for Friends, the private Quaker school where his parents send him despite his father's pronouncement to a TV interviewer that he's "never found a school in the United States run by whites that adequately prepares black children to enter the world as sane human beings." The public high school he attends next is a nightmare, but also the occasion for some of Asante's most electric writing:

The cafeteria: bananas, pure chaos. The benches and tables are bolted down and midget-low from when this used to be a middle school. There’s always a couple fights during the first lunch, mostly girls, haymakers and windmills, boobs popping out like Jell-O, spinning, spitting, a lot of hair pulling. The fights leave weave tracks and braids scattered on the floor, right there with the spilled milk, baked beans, and textbooks facing down, pages open like dead birds.

Asante's prose is a fluid blend of vernacular swagger and tender poeticism; it's no surprise that when he finally finds his feet again, the place he feels most affirmed is a spoken-word club. But first he traverses an underworld of hoodlums, lunatics, drug fiends and the kind of girl who frankly tells him men "are like bank accounts. Without money, they don't generate interest."

Malo sells weed for a while and watches his brother's old friends on the corner cycle through conspicuous consumption, a millenarian black nationalist cult and finally addiction. They ask him to buy "breakfast" when he drops by for a visit, and this takes them to a blasted urban wasteland ("Everybody's eyes curry yellow or smog gray, dead as sunken ships") where one buddy explains it to him: "'Pancakes,' Ted says, holding up the Xanax pills -- zannies. 'Syrup,' with a styrofoam cup full of lean -- promethazine and codeine syrup. He drops the pills in the syrup. 'Breakfast.'" Malo's best friend, Amir, is murdered, possibly by Malo's own weed supplier.

Adolescents are notoriously myopic, but one of the great strengths of "Buck" is the range of perspectives and voices Asante weaves into what might have been a one-man show. His mother's diary entries are the most obvious way he widens this memoir's scope. But Asante gives generous attention to the characters who wander through his story, from Dah, a Cambodian kid from neighborhood ("Uptown's MacGyver ... Give homie some duct tape, a couple of paper clips, batteries, a tube sock, and like two and a half hours, and he’ll make a better version of anything they sell at Radio Shack. Once he even made a bulletproof vest out of Kevlar strips he ganked from some old Goodyears") to the old friend who smokes Pall Malls instead of Newports because "I like designer clothes, Versace, Moschino, Polo, but I'm not paying for no designer name-brand cancer. Give me the cheap shit."

What saves Malo is a last-ditch effort on his parents' part and alternative education. At Philadelphia's Crefeld School he discovers a passion for writing, and if his teachers are full of pat mottos ("You don’t need to be great to get started, but you need to get started to be great"), it is nevertheless one of them who tells him that wanting to write "means you have to be a good reader, though." Confession: I'm a total sucker for first-person accounts of kids whose lives were transfigured by books, and Asante's delivers an ecstatic payback in this department. He finishes "On the Road" in one day and soaks up James Baldwin, Zora Neale Hurston and Walt Whitman like thirsty ground in a heavy rain. "Buck" grew from that, and it's a bumper crop.

Shares