The big revelation in "Salinger" (the film) and "Salinger" (the book), both to be released this week, is that rumors of a vault of unpublished manuscripts by the author of "The Catcher in the Rye" have turned out to be true, and, furthermore, that some of these writings continue the stories of the Glass family and Holden Caulfield. Less exciting (a lot less exciting) is the news that at least one of the manuscripts (which will be published between 2015 and 2020) is a "manual" for the Vedanta religion, the faith that engrossed Salinger for the last 50 years of his life.

Book and film also feature biographical information from new sources, most notably Jean Miller, a woman Salinger met in 1949, when she was 14, and with whom he had a quasi-romantic friendship for about five years. (Salinger dismissed her the day after the relationship was consummated.) Miller was the inspiration for the title character in his story "For Esme, with Love and Squalor."

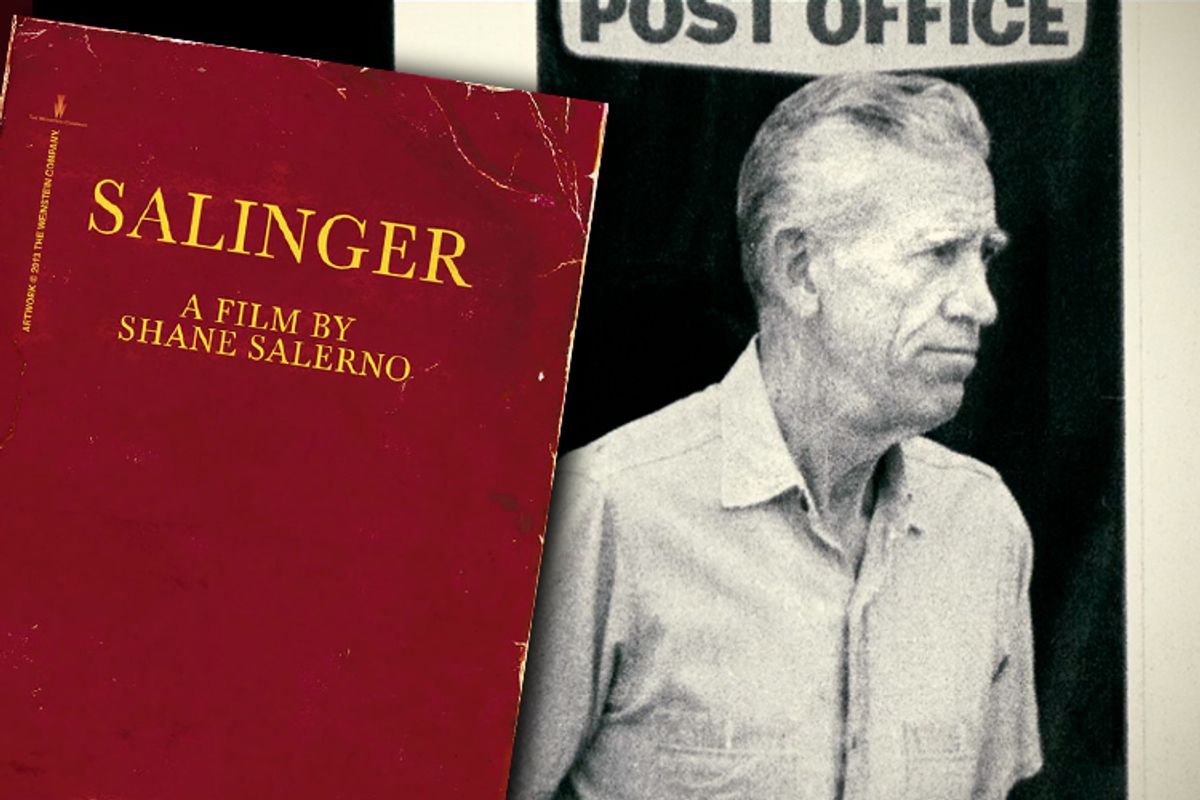

Apart from such discoveries, the film's director, Shane Salerno, and his co-author on the book, David Shields, offer some theories about Salinger's life and work: specifically, the persistent question of just what was wrong with him. As both book and film amply document, the author was a terrible father and worse husband, a man who withdrew from public life and repudiated his fame, yet was not above using that fame (via creepily seductive letters) to court teenage girls from his redoubt in Cornish, N.H. He was so merciless a perfectionist that he broke with a lifelong friend when the man, an editor, inadvertently allowed one of Salinger's short stories to be published in a magazine with the wrong title. He once threatened his family's former nanny with a gun when she came to his door collecting for the Red Cross drive.

Salinger wasn't a recluse; rather, as the authors stress, "what he wanted was privacy." This is often treated as the most outlandish aspect of his personality, when really it's the most commonsensical. One of the talking heads featured in the documentary belongs to actor Philip Seymour Hoffman, who explains that people who haven't lost the ability to walk anonymously down the street cannot appreciate what a tremendous freedom it is. "I'm tired of being collared in elevators, stopped on the street, and of interlopers on my private property," the elderly Salinger griped in a rare interview. "I want to be left alone, absolutely. Why can't my life be my own?"

The film features a fan who, as a young husband and father, traveled to Cornish to haunt the end of Salinger's gravel driveway, believing that the author "felt like I did and we could talk about deep things." Salinger, after asking if the man was "under psychiatric care," questioned how he could have left his family for such a quest. In this respect, if few others, Salinger was decidedly less crazy than the society around him. The attention trained on him was pathological, and his withdrawal from it entirely understandable, but the more he pulled back the more hotly the popular obsession burned. Another man interviewed by the filmmakers is a photographer who hid in the bushes outside Salinger's house and surreptitiously shot the writer as he walked his dog.

Both book and film versions of "Salinger" are refreshingly frank about their subject's many shortcomings and how they might have affected his work. The playwright John Guare, who appears in the film, notes that any writer would find cause for concern in having his novel held up by not one, not two but three separate assassins when they were asked for an explanation for their crimes. Salinger himself said he regretted writing "The Catcher in the Rye," mostly because of the attention it drew to him. The film also refers to Mary McCarthy's famous takedown of the Glass family stories, "J.D. Salinger's Closed Circuit," in which she accused him of creating a fictional hall of mirrors in which his own self was replicated and congratulated for its brilliance, charm and integrity over and over again. (This argument is briefly and eloquently translated into images, using the film's recurring visual motif of a besuited man typing tormentedly on a movie-theater proscenium while scenes from Salinger's life are projected behind him. The motif is otherwise comically histrionic.)

Salinger's genius lay in his seemingly unfettered yet acutely focused voice, for the way that it released the irreverent impulse trapped within the confines of postwar America. In "Catcher," he distilled the fiery, even Puritanical spirit of adolescence, with its tremendous energy and its vast blind spots, into the purest form imaginable; the novel is to youth what crack is to cocaine. In the middle of "Salinger" the film, amid the Errol Morris-style reenactments and the Ken Burns-style documentary footage, the movie opens into footage of young people all over the world reading or holding up copies of "The Catcher in the Rye," and it's impossible not to be moved by the spectacle, even if "Catcher" wasn't that book for you. It's that book for so many kids -- and the more power to it, for their sake.

But the grown men who turned up on Salinger's doorstep seeking conversations about "deep things" and the Mark David Chapmans (and John Hinckleys and Robert John Bardos) who saw "Catcher" as a call to strike down the world's "phonies," were not so much liberated into adolescent skepticism as trapped in adolescent angst. They turned to Salinger because he seemed to understand exactly how they felt. Whether they realized it or not, they were trying, and largely failing, to grow up, and they thought Salinger could help them. Unfortunately, they'd come to the wrong man because Salinger never figured it out himself.

"His writing was all about innocence and the damage done to innocence by the world," E.L. Doctorow says in "Salinger" the film, registering as one of the more thoughtful and adult voices reflecting on the work. Too many of the other commentators are actors (all male) who express more enthusiasm than understanding. For Shields and Salerno, Salinger's preoccupation with innocence and its desecration largely originates in his World War II experiences, which were brutal. The author participated in both the D-Day invasion and the liberation of a concentration camp. Salerno and Shields argue that "The Catcher in the Rye" "can best be understood as a disguised war novel." Salinger's rejection of public life can likewise be seen as a lifelong response to trauma. The film dissolves from his famously soulful author photo for "The Catcher in the Rye" to Ted Lea's equally famous illustration of a harrowed soldier, "That 2000-Yard Stare," with the eyes of both images superimposed on each other.

As for Salinger's idealization and pursuit of teenage girls -- a penchant that seems to me of a piece with his general fetishization of immaculate youth -- Salerno and Shield see two causes: heartbreak over Oona O'Neill, an early love who married Charlie Chaplin while Salinger was at war, and sexual insecurity caused by having "only one testicle" (or an undescended testicle, which seems more likely).

But "Salinger" the book also includes an anecdote about Salinger's apprenticeship (imposed by his father) to a meat company in Vienna in the late 1930s, during which visit he fell in love with Viennese girl of 16. Salinger later fictionalized her in a story titled "A Girl I Knew," praising her "immense eyes that always seemed in danger of capsizing into their own innocence ... When she sat down she did the only sensible thing with her beautiful hands there was to be done: she placed them on her lap and left them there." The man's fixation on very young, large-eyed and exquisitely simple girls seems to have been well in place before Oona broke his heart and the war ravaged his spirit.

Isn't it just as likely that Salinger went into the war a rigid, unforgiving man, and that the war broke him in the way it broke many others, but all the more so because he lacked the flexibility to absorb its terrible truths? "Salinger" (book and film) amply documents the author's youthful arrogance and selfishness, his infatuation with his own cleverness and his inability to see the world from the perspective of anyone who wasn't a lot like himself -- or whom he could imagine to be a lot like himself, as he did at the beginnings of his many short-lived romances. These traits preexisted the war and Oona's "betrayal," and this, combined with his immense, innate talent, may have given his fiction the concentration and the vividness that make his depictions of young people so persuasive. Besides, Salinger famously carried six chapters of "The Catcher in the Rye" with him on D-Day, the first action he saw. That novel, too, at least partially preexisted the war.

It's not always easy to accept that what gives some artists their access to greatness can also stunt them as human beings. In a few, rare cases, the work transcends the hobbled souls who created it. Only nostalgia could interest me in the further adventures of Holden or the Glass family. But also waiting in that cache of manuscripts are at least two books about grown-ups, set during the war, and I am more than a little curious to see what Salinger made of that.

Shares