Early Days

God, how it hurt. I walked along at my usual slow pace. Every time either foot touched the ground it felt like needles stabbing into the bottom of my leg and traveling like inverted lightning upwards. I concentrated on keeping moving, knowing that at the end of the next block I could sit down on a stoop and wait for the trolley. It was a cool day in late September, school had let out a half hour before, and so far I had navigated only two of the three-block trek to the streetcar line. Before I reached the end of the first block, my clothes were soaking wet under my lightweight jacket. I had acquired the ability to endure the persistent pain and continue with whatever physical activity was at hand without revealing my discomfort, but I could not prevent the perspiration.

Finally, into the last block, I had to pass the high wooden fence and that always required extra self-control. Just keep going, don’t look at them, maybe today they’ll forget about me. I looked straight ahead. No such luck. They were there, waiting for me, two little boys, probably five or six years old. As I approached they climbed up the inside of the wide board fence and sat precariously on the two by four top rail. “Here he comes. Hey, Mum, here he comes.” I was their treat for the day as I continued my tortured walk, slowly approaching them, trying to ignore them, my lower legs five inches shorter than the norm, my left foot pointed to the left at a right angle to my body, the right one angled to the right and my only hand, the left one, holding my books against my chest aided by my right arm which ended short of the wrist. “Look how funny he walks. Hey, Mum, see him?”

Mum’s face appeared above the fence line, staring as one with her two ignorant offspring. I plodded along, looking everywhere but in their direction, refusing to let them know that I noticed. As I passed by I could hear them scrambling down off the fence, the screen door slamming as Mum went back into the house and the childish chatter slowly faded away. With a sigh of relief I rounded the corner, waited for a car to go by, crossed the street and sat down heavily on a three-step wooden stoop near the trolley stop. Slowly I lifted my feet off the ground, one leg at a time, to relieve the pressure. The right foot began to have a series of spasms, like knives piercing my flesh. The left one thumped as the blood returned to the minimal tissue in my misshapen overburdened feet. Slowly, the pain subsided. Being careful not to bear weight on them, I rested my feet once again on the concrete pavement.

The trolley was late. That was good. The longer I could rest on the stoop, the easier it would be to walk home when I got off the trolley. Although there were many times when I wished I were not different, I never dwelt on it. I was what I was. I was a fatalist; I didn’t waste my energy on wishing for miracles.

* * *

Although very young at the time of this experience, it left a lasting impression. Even at such a young age, I understood that I was an object of curiosity and my presence could invariably generate a variety of reactions, from astonishment, or sympathy, to curiosity, or sometimes open revulsion. I couldn’t change it; it wasn’t something I could do anything about; I just had to learn to endure it.

As I grew older it became apparent that most reactions to my disabilities were casual and although there were exceptions, few people would go out of their way to pursue their curiosity beyond the casual level. I also quickly learned that the more of myself I revealed, the more curiosity and interest I aroused. I don’t remember thinking about it in my early years, but I was aware that, conspicuous as I was, it was important to make every effort to make myself as physically inconspicuous as possible, and to try to be as normal as possible. Into my adult years, I was never able to reach the point, even in the presence of friends, of feeling comfortable removing my shoes, or even my pants, which revealed my misshapen legs. I was always concerned that such an action would invite inquiry and I developed such antipathy to any concentration of attention to my disabilities that I avoided it at all costs, in all probability complicating my life rather than simplifying it. In later years I often asked myself if perhaps life may have ultimately been easier had the ignorant curiosity of casual acquaintances or strangers been simply obliged.

* * *

The Decision

Dr. Alan Russek was a tall man of ruddy complexion, with a bit of a stoop. His kindly expression and sad eyes were both gentle and thoughtful and his professional composure when we met did not hint at his actual feelings on seeing me, but I sensed that my appearance surprised him. I was unaware of it at the time, but my situation proved to be, for Dr. Russek, quite special. He was both amazed and intrigued. He invited me to sit and I reviewed our brief phone conversation, “Since I’ve become an adult, I’ve had no reason to be examined. Before that, my advice was always to leave well enough alone. So far I’ve been able to do anything I needed to do.” Russek studied me. “And what prompted you coming here at this time?” I responded, “Well, my current job was funded by a grant and now it’s over. I always have difficulty finding jobs, and I’ve just learned about the Institute, so I thought it might be a good time for another diagnosis.” Russek asked me to remove my shoes, which I did and he stared, shaking his head slowly. “Do you have much pain?”

“Yes, quite a bit. I’m fine when I start out in the morning, but I can’t go too long without having pain.”

“What do you do then?”

“If I can sit down, I do, otherwise I just keep going.”

“Were you in pain when you entered here?”

“Yes.”

“You didn’t indicate it.”

“I’ve learned to keep it under control.”

The examination proceeded and I noticed, as we talked and Russek looked, touched and probed, that he seemed totally amazed that I was as active as I was, and able, at the age of thirty-four, to still function. He approached the situation tentatively. “What is it that you think you would want done about your situation?”

“I really don’t know. I have no idea what possibilities might exist.”

“Do you think you might want to consider surgery?”

“If that would provide some improvement, I suppose so, but I have no idea what that involves.”

Russek leaned back in his chair and gave me a long, serious look. “You know, the reason you have pain is that, for many years, your weight has been concentrated on a very few square inches of bone at the bottom of your legs. You have no arch or spring mechanism to absorb the shock. You have insufficient area to which to distribute the weight. In short, the ends of your legs are severely overloaded. Here on the left leg you’re bearing your weight directly on the bottom of the tibia on less than four square inches of area.” He pointed to the left foot. “You see here, you’ve built up a callous to protect the end of the bone. Notice that with the constant beating over the years, the bone has begun to spread. It’s the same kind of thing that happens if you pound on a stick with a hammer. Notice also that it’s cyanotic, it has a bluish tinge. That’s because there is an insufficient blood supply to this area and insufficient flesh there.” He leaned forward and said very softly and earnestly, “I believe I can help you. You are very fortunate that you have been able to function for such a long time and right now you are in no immediate danger, but if this situation continues, now that you’re thirty-four years old, you will eventually develop some vascular problems and that could well complicate your situation and probably require your legs to be amputated at the level of the knee. If that were to happen, it would be very unfortunate because right now you have two good functional knees. Might you be willing to consider amputation?”

Amputation? That was a frightening word. It had never entered my mind that I’d be asked such a question. I was shaken. “That’s a frightening thought. Can you tell me more about what you’re suggesting?”

“Yes of course.

“A couple years ago at the University of California, Berkeley, a new, fiberglass leg was developed which is uniquely made for your situation. This new leg is designed to distribute your weight here,” Russek grasped both my legs in his hands, fingers stretched around them just below the knees where the bone begins to narrow, as if he were holding a glass. Russek pushed upward. “That doesn’t hurt, does it?” It didn’t. “That’s how you’ll bear weight in a prosthesis which will be held on by a light weight leather strap around your leg above the knee with another strap to a belt around your waist worn under your clothing. Your legs would be amputated about six inches below the knee. The artificial legs would look perfectly natural and your knee action would be unimpeded. You would be able to stand and walk, probably much longer and farther than you can now and without pain. Your normal height would be a bit taller with prostheses, and your condition would be stabilized. Development of vascular disease would be prevented.”

Was it actually possible that my situation could at long last be improved? I became overwhelmed with seemingly unrelated thoughts, remembrances of happiness, of pain, of thoughts long relegated to a back corner of my mind as being completely impossible. Now it was all tumbling back into the open. Russek was telling me that my impossible, repressed dreams were indeed possible. I had already reluctantly, but pragmatically accepted the idea that I would live out my life alone, without companionship of wife or parenthood. I had made that analysis, then put it out of my mind and gone on with my life. Emotionally I yearned for the companionship that I witnessed daily in the lives of others around me, but intellectually I had concluded that there were very few women who might possibly find me of interest and the odds were that I would never find them. After all I was thirty-four years old and apart from a brief relationship at the age of nineteen, for which I had been unprepared and inexperienced, there had been little else. I had thought it through time and again and always came to the same conclusion: It was how it was going to be and I would live with it. I had locked my dreams away behind a thick wall.

Now a jagged crack had just appeared in that wall and behind it was a dammed up flood of emotions and dreams that I had tried so valiantly, or had it been foolishly, to repress? All those emotions now began bursting out of that remote corner of my being, growing and expanding like a genie out of a bottle, and engulfing me with visions of a future about which I had long ago ceased to dream. My exuberance could not be contained. My thoughts flew, bounding and stumbling over each other, a montage of flashbacks, of my twisting and squirming trying to get out of the spotlight of people’s stares, my constant pain, lack of employment, and non-existent social life. Now I had a momentary vision of myself standing in the midst of a crowd of people: no one staring; I was standing there at ease and I wasn’t in pain. I appeared to be as normal as everyone else.

This all went through my head in a matter of seconds and just as quickly my thoughts returned to the reality of Russek’s office. It was a wonderful idea, but it could never happen. I looked at him. “What you’re talking about would have to be a very expensive undertaking,” I said, “I don’t see how it could be possible. I don’t have any money.” Russek smiled, “If you decide to go ahead with this, I don’t think you’ll have to have any money.” He was saying it could actually happen?

“I have to think about it, Dr. Russek. It’s a big decision.”

“Of course, we’ll talk about it again.”

A few weeks later, at Dr. Russek’s invitation, I visited with a group of his medical students who were studying orthopedics. The visit confirmed my feelings that Russek believed my situation to be an unusual case. He again asked me to remove my shoes as he explained my medical condition to the student physicians.

Russek’s suggestion remained on my mind constantly, but I wasn’t yet ready to commit myself. I had always been a risk taker. Now I was being offered a risk beyond imagination, a chance to realize my ultimate dream. Whatever the downside, I could not bring myself to believe that it could be worse than my current situation. I called my parents and explained the situation to them. Their reactions, like my own, were a mixture of joy and fear; joy at hearing that there was finally a possibility for my condition to be vastly improved, something none of us had dared to think about, and fear of the unknown: perceived risks and procedures I must undergo.

For thirty-four years they had carried the burden of my disabilities on their consciences. Their questions were the same ones that had already gone through my mind. What might happen if everything did not go as expected; if my legs were amputated and the prostheses didn’t function — how would I get around — would I have to use a wheelchair for the rest of my life? For me, hope overrode doubts of each fear.

In this office again, Russek introduced me to Irving Weissfeld. Mr. Weissfield, a soft spoken, middle aged Jewish man of short stature, was a case worker for the New York State Office of Vocational Rehabilitation which was the agency that could make it possible for me to have the surgery and to be fitted with artificial limbs. In short, if approved, OVR could underwrite my entire rehabilitation. From the conversation between the two men it was obvious that they had worked together on a number of occasions and respected one another. “This is a unique and special case, Irving. You must get full approval for everything we need. It has to be complete,” Russek stated very seriously. “I understand, Alan,” Weissfeld replied, “but you know there’s no precedent for underwriting a complete rehabilitation when there is no immediate medical need.”

This was a matter of considerable importance. A primary consideration in underwriting an OVR rehabilitation service, was that the assistance must enhance the recipient’s ability to be employed and become more independent.

The crucial portion of the appeal for underwriting was Russek’s argument that although at the moment the applicant was not in a critical situation, in a matter of a year or two he would be, at which time rehabilitative efforts would offer fewer opportunities for success than they did at the present time. That placed the argument into the category of preventive rehabilitation, and preventive rehabilitation per se was unprecedented in OVR’s rehabilitation funding policies.

I was now becoming acutely aware of Russek’s professional as well as personal interest in my case, but still didn’t fully understand the reasons. I didn’t realize then that Russek’s response to my situation was a very singular one, a unique challenge. In his daily practice he faced problems of how to facilitate the greatest possible salvage of bodily functions to maximize the restoration of capabilities and functions that had been lost due to trauma and disease. In each instance the post-rehabilitation condition, in even the most successful cases, resulted in a lesser capability or function than had been present prior to the affliction. My situation was just the opposite. My successful rehabilitation would create function and capability that was vastly improved over that which previously existed. My situation was that one-in-a-million occurrence which offered Dr. Russek an opportunity to use his skills to make whole and more capable, a body that had always been incomplete and disabled. Russek viewed the situation as one that not only provided a great opportunity, but also enormous professional and human satisfaction. I perceived it as a potential miracle.

* * *

On the 22nd of December, Dr. Ernst Bergmann amputated both my legs six inches below the knees.

* * *

In the Intensive Care Unit I had become aware for the first time of a feeling I had never before experienced. I had always known that my lower legs and feet were what set me apart from everyone else. It wasn’t a simple matter; it was complex and at the very center of my psycho/physical being. One had only to look at my legs and feet to know that they were very unusual,

To those who asked too many questions or wanted to see more, my response, sometimes politely, and sometimes less so, was simply, “It’s none of your business.” It always amazed me, and in many instances angered me, at how direct and insensitive a very large segment of the public was or could be. When they wanted to know something, they simply asked, and they had no awareness of how their inquiries impacted the feelings of those asked.

My early defenses resulted in my being very protective with regard to revealing the precise nature of my disabilities and ultimately resulted in my refraining from participating in a variety of activities that would require the removal of my shoes. In most cases a simple “No thanks,” or “I’d rather not” were sufficient deterrents to those who, in complete innocence and desire to be friendly or helpful would invite me to go wading, swimming, or sleep overnight. Despite my appearance, I was so physically able, I “passed” so well, that they projected their own activities and abilities on to me. Everyone assumed that I could do anything I wished to do; I could never bring myself to tell anyone that if I took my shoes off I could not stand, much less walk.

In the hospital, in the Intensive Care Unit, I was relieved that those feet and lower legs that had been the source of life-long pain and

humiliation, and a magnet for mindless stares of legions of strangers, were gone. Nobody would ever stare at my feet again. Never again would I experience that three part sequence which I had grown to detest: first the stare at my feet, then the penetrating look directly in the eye which conveyed, mirth, derision, shock, embarrassment, pity or compassion, which I returned directly and in kind, and finally back again to my feet, to confirm they had actually seen what they thought they saw, and to record a clear mental image so that they could recall it later. The congenital deformities that had for so many years affected my life and behavior were gone and in their places were two clean, surgically sculptured antiseptic stumps of natural, normal flesh and bone. What had also disappeared was the need to cover, conceal, mask or camouflage any part of my body.

The impact was significant. As I recovered from surgery, tension flowed out of me and relaxation set in. For the first time in my life I was completely at ease. All guardedness disappeared; I opened up. My physical body had nothing to hide. I became almost an exhibitionist. I did not care who saw me in any stage of undress. I almost begged to be seen. I had never known such freedom.

* * *

At the Institute, in an environment of progressive disease and post-trauma, every patient was fighting to regain or maintain some vestige of physical and/or mental control of his/her body that had been recently lost, and hoping against hope that some small increment of improvement would result in the next day, or week, or month; that nerves would mend, paralysis lessen, movement improve, and miracles happen. I alone possessed a body that was infinitely better than it had ever been. As I became acquainted with my fellow patients and heard their stories, that reality grew in me daily. Others were learning to live with the results of disaster; I was experiencing a miracle. I had more going for myself than anyone else.

* * *

I was in the Intensive Care Unit at New York University Hospital for twenty-two days, and I’d had no contact with other patients, not unusual since patients in ICU were all in need of critical attention. The Institute, however, was a completely different environment. It was not a hospital per seʹ. The Institute’s focus was physical and educational rehabilitation; entertainment and social activities were encouraged as a means to assist restoration of patient independence.

Entry into the Institute brought with it the realization that, despite the improvements in my personal physical condition, I was nevertheless a severely disabled individual and thus one of a group who were labeled handicapped. That had never been my orientation. I never perceived myself as belonging to any such group, but now I was at the Institute with other handicapped people. Without question, I was one of them, and there was no escaping the fact that in this particular zoo, I was not one of the keepers.

Being fitted with lower leg prosthesis is a bit like learning to walk on stilts. The point of contact with the ground is beyond the extremity of the limb and one must learn to manage the dead weight of the artificial extension (prosthesis) that is attached to the natural limb. As long as it’s hanging down it can be swung more easily than if it is lifted up and forward, as in a high kick position. When lifted, the full weight of the prosthesis is extended from the end of the leg as a cantilever and strength and athletic ability is required to manage that dead weight and make it go where it is supposed to go. Accordingly, before being fitted for a leg, the leg muscle strength and tone necessary for the job must be developed. The first step in that development is to determine one’s existing physical condition so a base point can be established from which to measure future progress. The physical therapist that tested me wore an artificial leg of the same type that I was to have and I studied her carefully.

* * *

As a risk taker, I had always been willing to rise to almost any kind of physical challenge and had succeeded at whatever I had attempted, but my professional track record, although replete with numerous assignments well done, seemed always to result, on their completion, in my being placed back at square one. I was unable to parlay any of my successful achievements into better, more rewarding situations. Despite my remarkable metamorphosis and my good feelings about myself, I knew that professionally I hadn’t advanced. My lack of professional success and continued search for employment consumed me and filled my horizon.

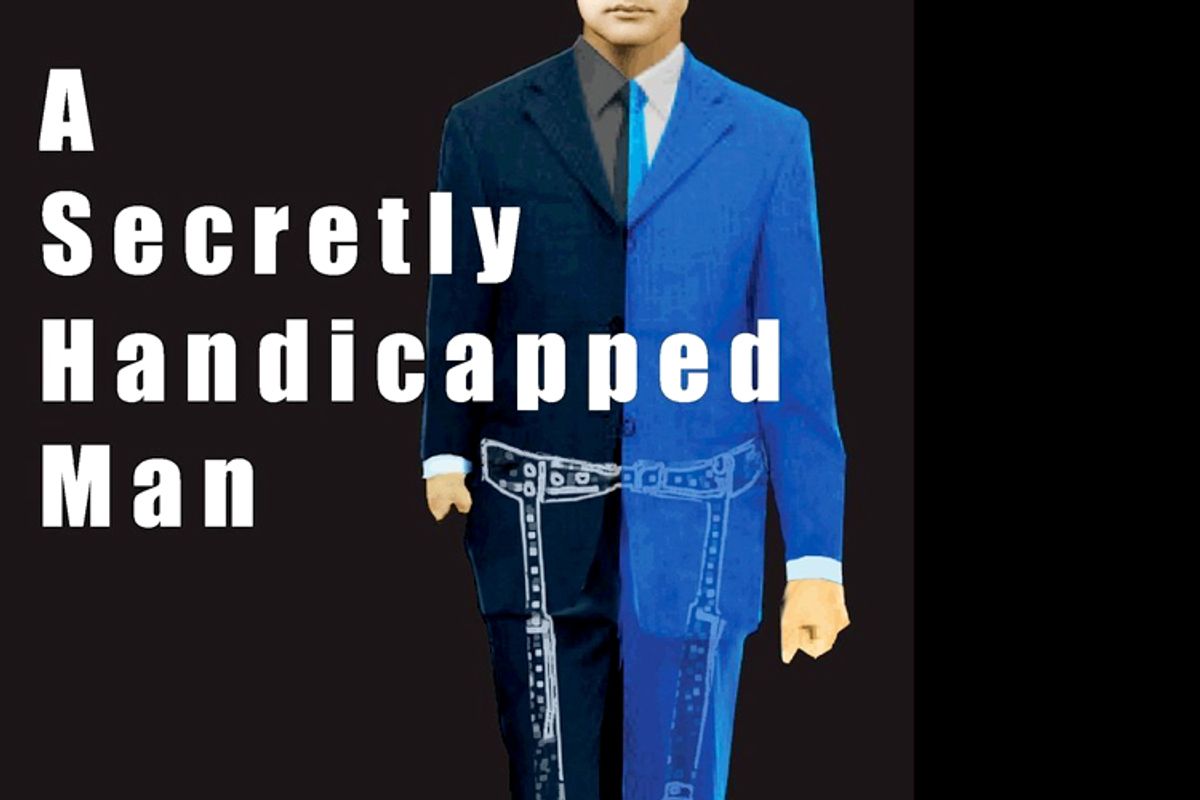

Excerpted from "A Secretly Handicapped Man" by Norbert Nathanson. Copyright 2013. North Wind Publishing.

Shares