By studying the interactions between our bodies and our microbes, a startup hopes to find new ways of treating disease.

The trillions of microbes that live in our bodies play an important role in our health and disease, but researchers have found that understanding this diverse and complex stew of bugs is daunting.

One company, Second Genome, has turned to DNA analysis and biochemical studies of mixtures of microbes and human cells in culture to better explain things. The company ultimately wants to identify therapeutics that restore balance to an off-kilter community by changing its composition or its effects on the human body.

The diversity of the human collection of microbial residents—known as the microbiome—became more clear last year when the Human Microbiome Project described the diversity and abundance of microbes living in and on the human body (see “Researchers Catalog Your Microbial Zoo”). For every one human cell in the body, there are an estimated 10 microbial cells. Changes in this microbial zoo have been correlated with many health problems: from gastrointestinal disease to diabetes, obesity, and inflammation.

“The microbes that live with us have a lot of impact on our health, positive as well as negative,” says Gary Andersen, a microbiologist at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and a cofounder of Second Genome. “But it’s been hard figuring out within an individual person what is a positive microbiome or community of organisms,” he says. That’s because from person to person, the structure of the communities varies greatly, he says.

One reason it has been difficult to profile an individual’s microbiome is that most of these organisms can’t grow in pure cultures of a single species. So Second Genome uses DNA sequencing along with another DNA analysis technology developed by Andersen to identify community members and to look at gene activity in both the bugs and the human body. “We are really focused on the interaction between the microbiome and the host,” says Second Genome CEO Peter DiLaura. The community of bacteria in our guts interacts with receptors and other targets in our body, he says: “When we think about therapeutics, it’s about impacting the interaction that is beneficial for disease.”

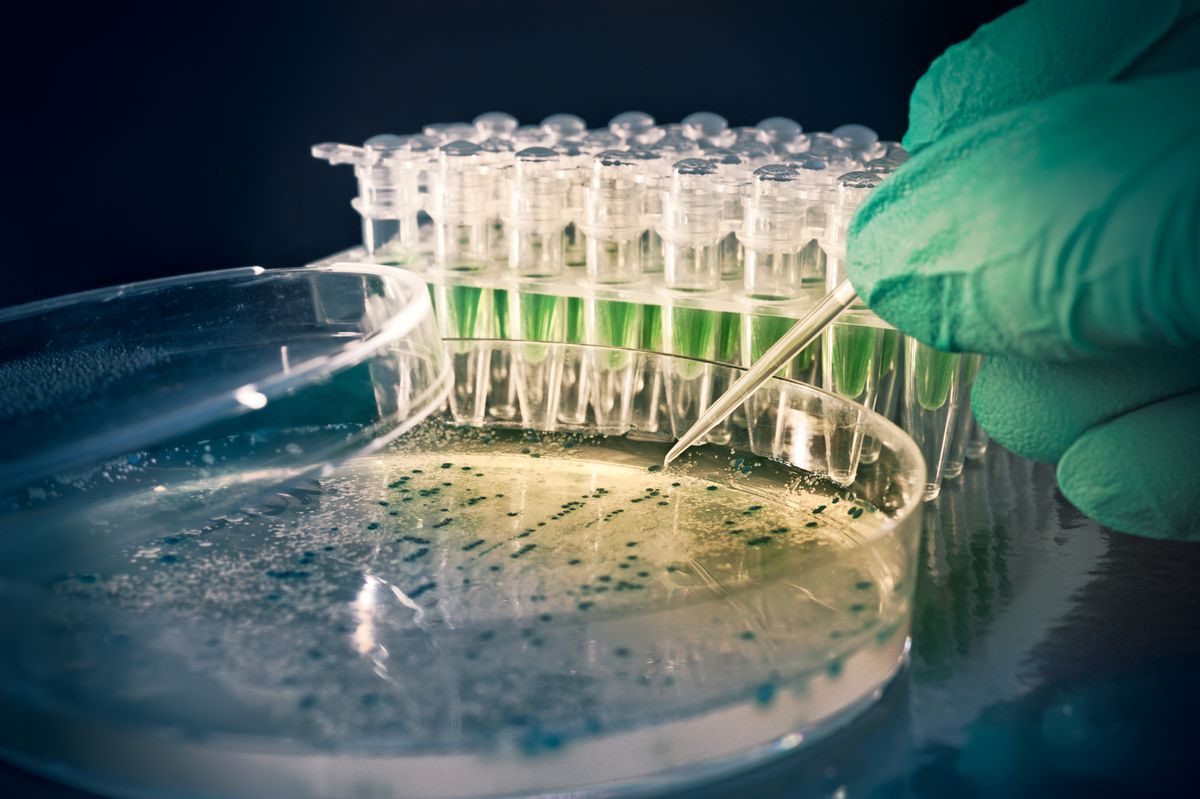

After DNA analysis, the company studies the interplay between microbe communities and human cells grown in culture. The next step would be to study the interactions in lab animal models of diseases. The hope is to develop a detailed understanding of how the microbiome affects human physiology, down to the molecular level.

The company is investigating the microbiome’s effect on inflammatory and metabolic disorders, including type 2 diabetes. “We have focused on places where there is reasonable evidence that the microbiome is playing a causal role,” says DiLaura.

In June, pharmaceutical and consumer-product company Johnson & Johnson invested an undisclosed amount in Second Genome. In return, Second Genome will search for potential drug targets to treat ulcerative colitis. Robert Urban, the director of J&J’s Boston Innovation Center, says his company is committed to the microbiome idea. Last week, Vedanta Biosciences, a microbiome startup also looking to microbial functions for drug discovery, announced a partnership with J&J.

Shares