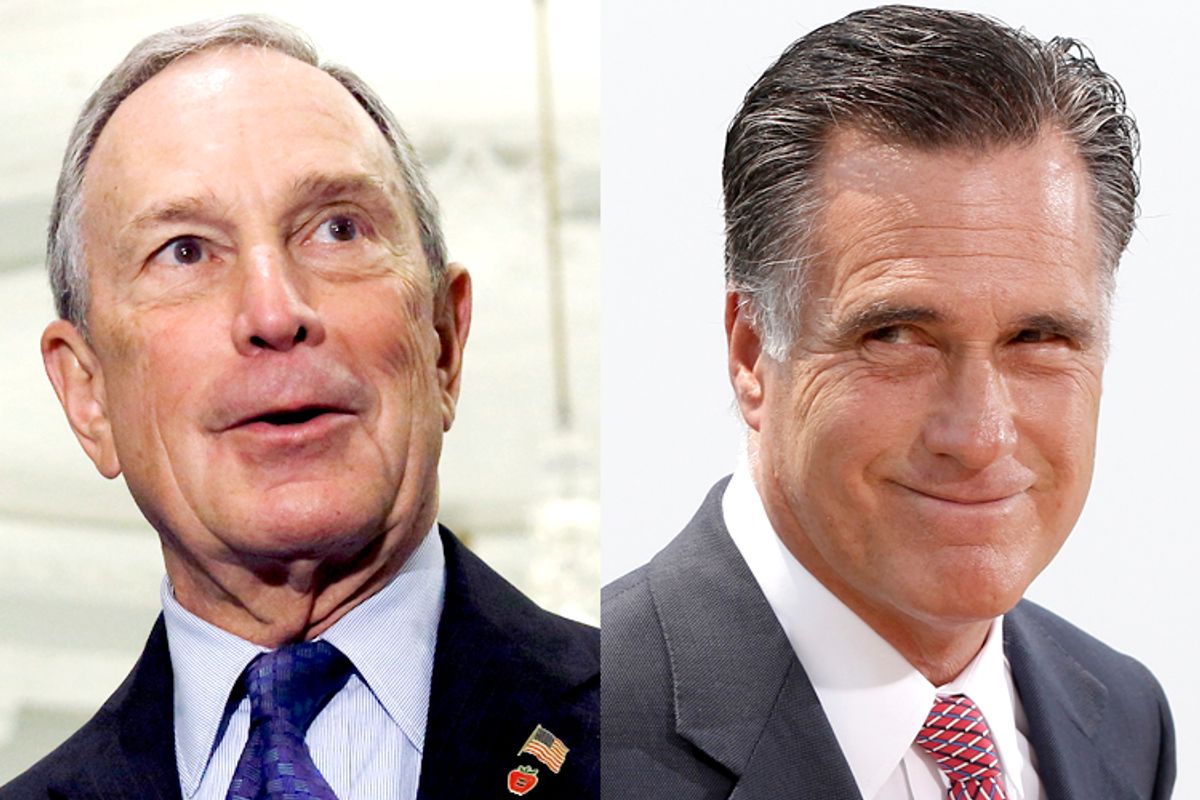

A few days before today's Democratic primary in New York City, Michael Bloomberg apparently deigned to leave his palatial estate in Bermuda and his $20 million home in London and fly back to the Big Apple. During that most recent trip to the city he rules in partial absentia, the billionaire CEO mayor granted an interview in which he offered up a farewell summary of his economic agenda. In the process, he provided a reminder that for all the political obituaries written about Mitt Romney, the plutocratic politics of berating the so-called 47 percent still persists.

In his now-famous interview with New York magazine, Bloomberg's whiney ode to Romney's "47 percent" line came when he dissed Democrat Bill de Blasio's crusade against economic inequality. Bloomberg said (emphasis added):

(De Blasio's) whole campaign is that there are two different cities here. And I’ve never liked that kind of division. The way to help those who are less fortunate is, number one, to attract more very fortunate people. They are the ones that pay the bills. The people that would get very badly hurt here if you drive out the very wealthy are the people he professes to try to help. Tearing people apart with this “two cities” thing doesn’t make any sense to me. It’s a destructive strategy for those you want to help the most. He’s a very populist, very left-wing guy, but this city is not two groups, and if to some extent it is, it’s one group paying for services for the other.

Just as Romney's "47 percent" comment expressed a "makers versus takers" hostility toward the plight of those in need, Bloomberg seems angry at the poor for being poor and resentful that the rich pay more into public coffers. Likewise, just as Romney's "47 percent" comment evinced an ignorance of the problem of inequality, so does Bloomberg seem unaware of his city's economics.

Meanwhile, in continuing the tradition of depicting the filthy rich as persecuted saviors, both of them seem unable to comprehend the basic connection between inequality and taxes. More specifically, they seem unable to understand that while many middle-class Americans pay a higher tax rate than the rich, the total amount of tax revenue from the poor is less than from the rich because in this new Gilded Age, the rich possess a disproportionate share of the economy's total cash. Indeed, to the extent that Bloomberg is mathematically correct in suggesting the wealthy contribute more to New York City's tax coffers than the non-wealthy, that reality is not because the city's poor are tax scofflaws. It is because a comparatively small group of rich New Yorkers possess the lion's share of the city's total cash supply that could be devoted to the public coffers.

In New York City, that mathematical reality should be especially obvious because the Big Apple is the most economically unequal city in one of the most unequal states in one of the most unequal countries in the industrialized world. And Bloomberg's personal class war has only made that situation worse.

Yes, it is more than a bit rich (pun obviously intended) for a billionaire to at once decry class warfare and then make veiled reference to his own class war aimed at replacing New York's poor with his fellow aristocrats. And that's almost certainly what Bloomberg was referencing with his "attract more very fortunate people" line. After all, despite his Bermuda and London jet-setting, Bloomberg hasn't been a disengaged dilettante passively presiding over the Big Apple's Dickensian cataclysm. He's been an ideologically motivated plutocrat who has diligently worked in New York to comfort the comfortable and afflict the afflicted.

For instance, Bloomberg's tax- and budget-cutting agenda has been defined by evictions of the poor from low-income housing, big cuts to social services for the indigent and a P.R. campaign against proposals to raise his fellow millionaires' taxes. On the spending side of the Bloomberg agenda, there has been the closest thing in America to a Banishment Program -- a Bloomberg initiative to exile the homeless by giving them one-way tickets out of the city. There has also been ongoing massive taxpayer subsidies to Wall Street banks and other corporations. And, of course, there has been Bloomberg's regulatory and enforcement agenda -- stuff like banning food donations to shelters and deploying police force disproportionately against low-income communities.

The predictable result is that Bloomberg's mayoral tenure has coincided with an epic rise in inequality and destitution, to the point where almost half of all New York City residents live at or near the poverty line. From a social engineering perspective, that has no doubt served the mayor's goal. He has at once made it better than ever to be rich and more painful than ever to be poor -- a reality that no doubt makes New York more attractive to the rich.

If Bloomberg's embittered crusade against the indigent was an isolated skirmish, it could be dismissed as an anomaly. But the direct line between his posture, Romney's campaign language and the right's intensifying blame-the-poor rhetoric suggests this is all part of a larger and ongoing class war that unfortunately is not ending. Just as the 2008 and 2012 elections seemed to promise a deescalation of plutocrats' class war and then delivered nothing of the sort, so too does today's vote in New York promise a real opportunity, but not a concrete conclusion.

Sure, it is good news that Bloomberg's economic record has been exposed and humiliated over the course of New York City's Democratic mayoral primary. And sure, Bloomberg leaving City Hall definitely opens up the possibility for an emboldened counteroffensive against that war in the Big Apple -- especially if an economic populist like de Blasio becomes mayor. But this is hardly the end. Under the best circumstances, it is merely a victory auguring a possible beginning of a progressive counter offensive. The end of this class war is still a long way away for New York and for the country as a whole.

Shares