The Evanston public library had, for years, a great used book room in the back of its North Branch that was a little-known treasure. People would donate large personal libraries of old hardcovers and amazing 60s and 70s-era paperbacks of everything from the classics of Western Literature to back issues of the Paris Review. There was almost always something to snag, and for prices that sometimes made me feel guilty for the three seconds it took me to reach for my wallet. There was rarely anything new or indie, but occasionally there would be extra copies of a Pulitzer winner or a lesser-known story collection of a major author like Margaret Atwood that got shipped off in the donate box. It was a disorganized room, so I’d always have to sift through the piles of mysteries and self-help books for the slim early twentieth century American novels of writers I was trying to create collections of: Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, and John Steinbeck, to name a few.

The Evanston public library had, for years, a great used book room in the back of its North Branch that was a little-known treasure. People would donate large personal libraries of old hardcovers and amazing 60s and 70s-era paperbacks of everything from the classics of Western Literature to back issues of the Paris Review. There was almost always something to snag, and for prices that sometimes made me feel guilty for the three seconds it took me to reach for my wallet. There was rarely anything new or indie, but occasionally there would be extra copies of a Pulitzer winner or a lesser-known story collection of a major author like Margaret Atwood that got shipped off in the donate box. It was a disorganized room, so I’d always have to sift through the piles of mysteries and self-help books for the slim early twentieth century American novels of writers I was trying to create collections of: Jack London, Ernest Hemingway, and John Steinbeck, to name a few.

I spent a little time last year in the Antioch Public Library. They were good enough to invite me to speak there, and because I love libraries I took half an hour to browse their selections and check out their used-book room. Used book sales at libraries are like a little pat on the head from God, as far as this writer is concerned, and I do my best to clean them out of anything and everything that looks interesting at their $1 price tags. Both for the sake of supporting the libraries that bother, and for the sake of my secret fantasy of one day converting my entire home into a library, negating the need to ever again leave one.

Here I discovered an uncomfortable truth: it’s entirely possible to fill a room the size of a Starbucks with nothing but very recent supermarket checkout novels by James Patterson, Mary Higgins Clark, Sue Grafton, David Baldacci, and Dean Koontz. I’m not kidding. I spent a good forty-five minutes combing this enormous used book room looking for something to buy that I could actually dig into. I’m not getting down on Patterson and Co. here; in fact I’ve read and enjoyed at least one novel of each of these authors and once upon a time I even considered Koontz to be a pretty clever writer of speculative fiction. But let’s face it: if you’ve read one of these authors’ books, and enjoyed it, you’re pretty much in for the same experience again and again with the rest. It’s a model that works for exactly the right reasons to be sold at the checkout counter of supermarkets.

It’s so easy—God is it easy—to poke fun at novelwriting machines like James Patterson. In the time it takes me to write this essay, he and his ilk will have exhaustedly wheezed out an entire Fall lineup to feed their devotees. But there’s something that tickles the back of my mind when I come to the realization that this particular used-book room is all about mass-market paperbacks: the corollaries of my youth that might have had places on these shelves are missing.

I’ve come a long way from being 15 and tucking into Mario Puzo’s The Godfather or Harold Robbins’ The Carpetbaggers. I’m not as hormonal, for one, and their flavor of 60s-70s sex and violence is more warmly reminiscent for me than it is truly exciting or illicit. Call it snobbery if you will, but I also have a much higher critical standard to which I hold genre or mass-market fiction now, 95% of which fails to pass muster. But somehow I can’t shake the feeling that Puzo’s and Robbins’ bodies of work, while just as commercial (Puzo) and occasionally poorly written or soulless (Robbins) as their present-day equivalents, are somehow still objectively better pieces of fiction to read.

If I were a scientist, I’d maybe say that the “nostalgia variable” is “difficult to control for.” There’s maybe a part of me that thinks I’ll always be eighteen again when I’m reading about how Domenico (father of the Clericuzio family of Puzo’s underappreciated The Last Don) refuses to eat a mozzarella that’s more than thirty minutes old. There’s a part of me that will always associate successfully-played revenge strategies with the phrase “So die all who betray Guiliano!” from The Sicilian. As a writer of close, near-future stories focused on small numbers of characters, I will always be jealous of Puzo’s ability to lean back and spin out a story that takes place in a Sicily so vivid that I can smell the olive trees and feel the sandy slopes of the bandit-filled hills above the town of Montelepre. Puzo’s gauzy Italian impressionism was every bit as formulaic a talent as Patterson’s pattern of weaving plucky duos of intelligent do-gooders with glaringly low libidos into the webs of demented and often sexually aggressive serial killers, but Puzo’s work still seems to hold so much more life in it than the further adventures of Alex Cross. They’re both pretty violent at times, and more than a little thematically repetitive. Is it just the sex, then? Is it the sex we’re missing these last few decades?

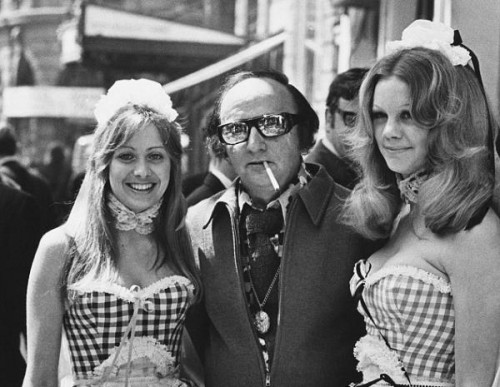

You will remember Harold Robbins, the man who… wait, what? You don’t rememberHarold Robbins? How can you not remember Harold Robbins? The guy is the fifth worldwide best-selling fiction author of all time. His work was only outsold by William Shakespeare, Agatha Christie, Barbara Cartland, and (narrowly) Danielle Steel. He published books up until his fairly-recent death in 1997, and even then continued Tupac-ishly, to “publish” twelve more books via ghostwriters since. This guy, this industry-defining figure, who sold enough copies of his books that one exists for every 9.4 people on the planet, is today almost completely forgotten. WhitherMemories of Another Day? Whither Descent from Xanadu? Whither Spellbinder? Forgotten. And maybe rightfully so. They’re mostly stinkers, with sometimes glaring plot holes and written at a sturdy fifth-grade reading level. But their wonky plots, full of thinly-veiled references to actual people and events; their ugly, frank sex scenes that somehow still manage to be better than the moronic, regressive nonsense in 50 Shades of Grey; their statement, as diffuse and warped as it was, about the times they were written in; we’ve lost that, somehow, and it’s given way to Alex Cross battling a new version of the same serial killer again and again, multiple times per year, and getting laid only inasmuch as it doesn’t distract from the gruesome ways in which sex can be used to hurt people.

When I think about that wall of books in the used-book room in Antioch, I feel like the Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come, showing Ebenezer Patterson the grave in which his career will be buried a mere fifteen years after his death. Harold Robbins was called “the man who invented sex,” for God’s sake. He gave the Baby Boomer generation—a generation so thoroughly devoted to themselves and their own pleasures that they invented or perfected basically every vice we have today and some that we no longer have because they were too dangerous to allow to continue—enough nipple-stiffening book-magic that he sold seven hundred and fifty million copies of his books. To give the uninitiated some perspective: an average, successful book today sells 20,000 copies. But be honest: you still had to take a moment to remember who he even was.

Back to my point: Puzo and Robbins bordered on being shlockmeisters, but they were, at worst, sex-positive schlockmeisters. I don’t mean to say they were fair about it. In fact, it was usually just the opposite. They wrote all sorts of chauvinist horseshit into their books. Piles of it. Men dominating women sexually and women unabashedly using their sexuality as a weapon: the great clichés of the late twentieth century. But at least in those years there were characters at the supermarket checkout aisle that seemed to like sex or at least confront it in vivid ways. Bookish people like to point to YA titles as being at the forefront of sex in literature, but I think this buzz is, and always has been, exaggerated. Yes, there are lots of excellent YA titles that didn’t exist when I was a young adult, but they’re not playing the same sport. Katniss uses her “look” to sell herself as a winner in a world defined by competition based on looks, but she shies away from relationships like they’re somehow tougher to tackle than the massive dystopian regime she takes on. Compare this to a minor subplot in The Godfather regarding Lucy Mancini. Lucy (who has only a tiny part in the film version) is the bridesmaid notable for having an affair with Sonny Corleone and having sex with him during Connie’s wedding. The film completely glosses over her storyline, but in the novel the stated reason for the affair is that Lucy has an abnormally large vagina and Sonny is hung like a horse (Horse? Wait? Is that…could it be… foreshadowing with imagery in a mass-market paperback? Are you lost, Puzo? Literature is in that aisle over there!). Lucy proceeds to mostly leave the family and settle down with a surgeon who performs what in those days probably read like mad science but today is known as a vaginal rejuvenation pelvic floor surgery, leaving her and her husband, ironically, as two of the only characters to make it out of the story happy and alive.

Does this translate into sex-positive literature? I’m not sure. It ain’t pretty, and the characters do submit themselves at times to the judgmental eye of the reader, but at least they seem willing to go ahead and want what they want. All over-the-top gonzo sex plots aside, these days the only mass-market literary characters that seem to enjoy fucking at all are psychopaths, sadomasochists and vampires. Make of that what you will, but I wonder: fifteen years after James Patterson dies, will we think of him as “the man who invented serial killers?”

Shares