The election of President Obama at the end of 2008 created a new predicament for the ruling group in Iran. His early declarations of openness to direct talks with the Iranians, his preparedness to speak of the Islamic Republic as such rather than in circumlocutory terms that avoided appearing to recognize the nature of the regime, as previous administrations had done, and his cleverly crafted Noruz message in March 2009 (in which, among other things, he spoke of "the true greatness of the Iranian people and civilization" and "your demonstrated ability to build and create") challenged the stale rhetoric of the Iranian regime and forced them to contemplate a change in their own policies of intransigence. But both sides knew that little could be expected to shift in the U.S.–Iran relationship in advance of the Iranian presidential elections scheduled for June 2009. Many people, both outside Iran and within, hoped the elections would produce an Iranian leader with a new, positive outlook to complement Obama’s, permitting some real progress at long last.

It was not to be. Once again, the Iranian presidential elections produced a surprise – all the more so because this time the surprise was of a different order altogether from the surprises of past elections. In 1997 and in 2005, surprise outsiders had won the elections. This time the surprise was in the conduct of the elections themselves, which led to weeks of demonstrations and unrest of an intensity not seen since the revolution of 1978–79.

In the last weeks before election day on June 12, 2009, many observers discerned a growing wave of enthusiasm for the movement behind the leading opposition candidate, Mir Hosein Musavi. A journalist wrote afterwards:

The run-up to the elections was unlike anything that the generations that grew up after the 1979 revolution had ever experienced. On these nights the police left the campaigners alone. It was as if a breeze of liberty was blowing through the streets. The cries and slogans that resounded were voicing demands which did not conflict with the Constitution.

However, the previous year’s message from the Leader of the Islamic Republic, addressed to Ahmadinejad’s cabinet, was not forgotten by the people. It had stated that they must consider planning for the years ahead. It was brought to attention by people like Mostafa Tajzadeh, who said in a campaign meeting that on the eve of the elections news had arrived that the personnel in the Ministry of the Interior had been changed. Alongside the fraction-by-fraction steps towards liberty, he seemed certain that we were on the verge of witnessing some serious events take place.

For the first time in the Islamic Republic’s election history, candidates debated with each other in the American style; publicly before the people. Heated words were exchanged about the country’s current policies on a platform provided by the media whose head is selected by the Leader. Prior to this, no one had dared to utter a word about the corruption of the sons of Hashemi-Rafsanjani and Nateq-Nouri in front of the Iranian government’s cameras. But now Ahmadinejad, in order to escape from being cornered, referred openly to these affairs, though, of course, he was not pushed by the Leader or any judicial institution to answer for this.

The televised debates caused an immediate reaction. The slumber that had characterised these years was left behind and people exploded out into the streets. The enthusiasm over the elections was at its peak.

Another commented on the televised debates (each candidate faced each other one-to-one in a series of programs broadcast between June 2 and 8):

The debaters’ bold and public criticisms of one another seemed to have lifted the dam of political censorship which usually prevented the people from saying what was truly on their minds. Society’s public atmosphere also became freer for the greater criticism and the expression of people’s true feelings. As a result, during the final month before the elections, everyone living in Iran, particularly in the bigger cities, witnessed a public enthusiasm, energy and excitement. The people were constantly speaking of a change of circumstances. Even in the days leading up to Mohammad Khatami’s victory in 1997, when he was elected president with an unprecedented 20 million votes, society’s public atmosphere was not as critical of the current conditions as it was at this time.

Having served as prime minister in the 1980s, Musavi had been out of politics since 1989 and like Khatami before him, he appeared to have neither the track record nor the charisma of someone likely to shake the foundations of the state. The perception of a developing movement behind Musavi was reinforced by early indications of a high turnout on the day of the vote, suggesting that pro-reform voters who had boycotted the elections in 2005 had changed their minds and turned out this time. There were long queues outside polling stations in Tehran; in some, the voting hours were extended and in others they ran out of ballot cards. All of this augmented the expectation of those on the opposition side that they were about to win a major victory, and this seemed to be confirmed when Ali Larijani telephoned Musavi at 5 p.m. on June 12 (in advance of the polls closing) to congratulate him.

But although the final results, when they emerged, certainly showed a high turnout – 85 percent – they gave not Musavi but Ahmadinejad a whopping 63 percent of the vote: well over the 50 percent threshold needed to win the poll outright (less than 50 percent would have meant a second round of voting, with a run-off between the two candidates who had won most votes in the first round).

No one has yet produced conclusive proof that the results of the presidential elections of June 2009 were falsified, but there have been a number of suspicious indications and pieces of partial evidence that, taken together, produce a consistent picture to that effect. One sign was that previous precedents for release of the results were abandoned – normally results emerged by region, but this time successive announcements were made on the basis of a larger number of votes counted each time, for the country as a whole. The distribution of votes for each candidate, when the final results were out, showed a suspicious consistency across rural and urban voting districts, and in those dominated by religious and ethnic minorities – as if someone had picked figures for the final result and had then applied that formula to each part of the country in arbitrary fashion, with the help of a computer program. Against all previous experience in Iranian elections, there was no significant sign of a swing towards candidates in their home districts: the proportional formula held up even there.

A defector from the Basij told a Channel 4 journalist later that they had received instructions through their chain of command that the supreme leader had decided that Ahmadinejad should win the election, and they should do all that was necessary to ensure he did. On the day, blank ballots and the ballots of illiterates and others were filled in for Ahmadinejad, irrespective of the actual wishes of voters; some ballot boxes were counted, but then all were sent back to ‘the center’ with most still uncounted.

The regime’s handling of the results deepened suspicions to the point at which the election looked increasingly like a coup carried out by the ruling group to keep Ahmadinejad in office. Several months before the elections, Khamenei had made statements supportive of Ahmadinejad that already marked a departure from previous practice. After the election results came out, Khamenei spoke forcefully in support of Ahmadinejad’s re-election within a few hours, acclaiming it as a divine judgement – previously the supreme leader had waited until the Guardian Council ratified the result, which usually took three days. Even before the final results were known, in the small hours of the morning, police and troops were on the streets to forestall demonstrations. They surrounded the Interior Ministry (from which the results were being announced) and Musavi’s campaign headquarters, severely hampering the opposition movement’s communications and their ability to respond to events. All these actions were unprecedented.

Over the following weeks a number of rumors emerged that, taken together, may go some way to explain how the election turned out as it did. It seems that the ruling clique became increasingly concerned in the spring of 2009 that the elections might develop a bandwagon effect comparable to that which resulted with the election of President Khatami in 1997 – an outcome they were determined to avoid. One version says that the government conducted a secret poll that showed an outright win for Musavi. Several reports purporting to come from dissidents in the Interior Ministry alleged that reformist-oriented staff were purged and swiftly replaced by Ahmadinejad’s supporters, who set about a plan to falsify the results. There were a number of suggestions that the cleric most closely associated with Ahmadinejad – Ayatollah Mesbah-Yazdi – had issued a ruling that all means were legitimate to ensure the continuation of the prevailing form of Islamic government – "everything is permitted."

There is little doubt that many voters did turn out for Ahmadinejad on June 12. The usual judgement is that his support was strongest in the countryside and in the more remote parts of Iran. Voters who distrusted both the regime and the perceived urban sophistication of the opposition candidates may still have voted for Ahmadinejad because unlike other politicians, he looked and sounded like them – they understood him and felt they could trust him in spite of his failure to reverse worsening economic conditions and standards of living in his first term. Many Iranians supported his strong stance against the West and in favor of Iran’s right to a civil nuclear program. In the smaller towns and cities outside Tehran and in the countryside it was also easier for the regime to coerce voters – whether by increases in salaries just before the election, or by threats. But one should not go too far (as some have) in characterizing the elections as a confrontation between an urbanized, Westernized, vocal minority versus a relatively silent, rural majority. The population of Iran in 2009 was more than sixty percent urban. It seems unlikely that more voted for Ahmadinejad in 2009 than did in 2005, when his opponent was Rafsanjani. One Western reporter, who went out of her way to speak to working-class Ahmadinejad supporters, found some that would be vocal in his support, only to whisper "Musavi" to her afterwards, when they could be more confident that no one was listening. But the suspicious behavior of the regime, the furor over the election and the demonstrations that followed may have obscured the real level of support for Ahmadinejad, especially for observers outside Iran. Significant numbers of lower- and lower-middle-class voters, including urban voters from those sections of society, whose support had always been crucial since 1979, had shifted their allegiance toward him after the failure of the reform movement in Khatami’s time. Whether those numbers amount to 20, 30 or even 40 percent of the population is hard to assess. But part of the story of 2009 was that Iran had become a divided country. The actions of the regime could be ascribed either to panic in the face of the growing opposition movement or to the desire to avoid the unpredictability of a second round of elections, or both.

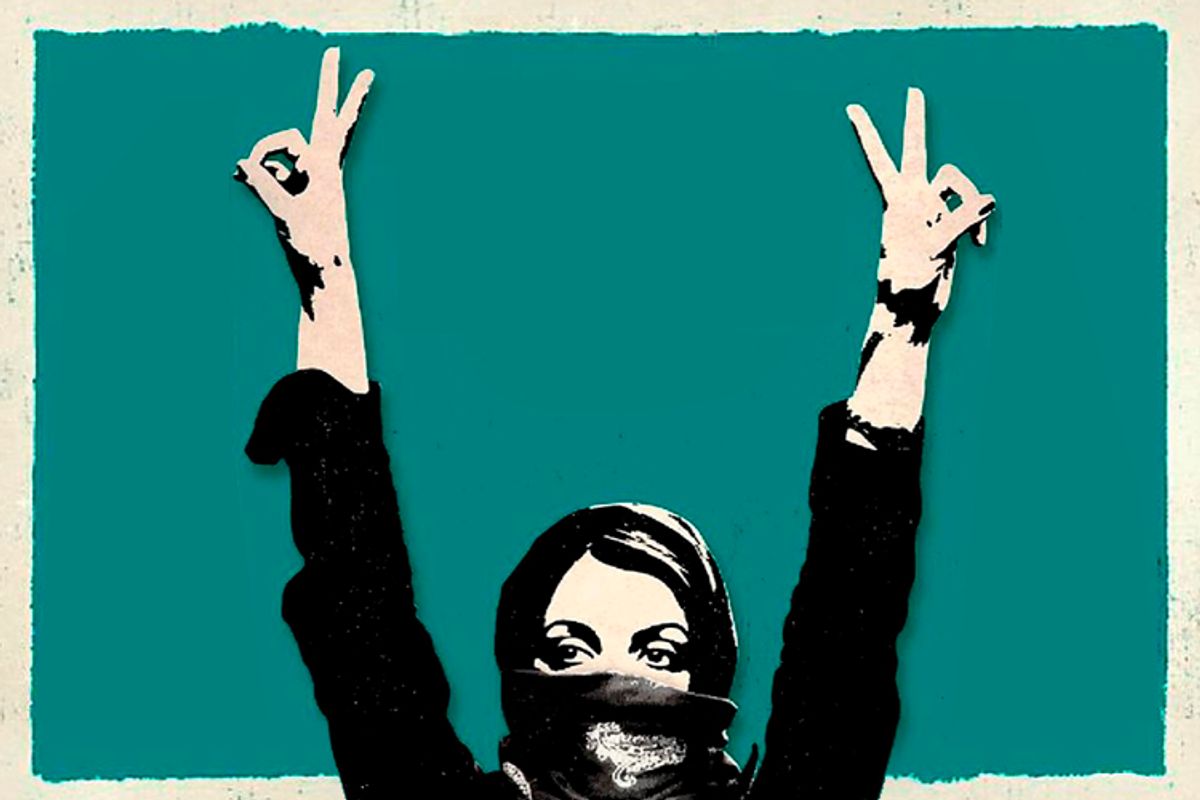

Whatever the truth of what happened, the immediate and strong reaction told its own story. Thousands of Iranians turned out on the streets of Tehran and other cities to protest, wearing scarves or bandanas in green, the color of the Musavi campaign. No previous Iranian election had produced such demonstrations. Within a few days, the number of protestors had grown to hundreds of thousands, with estimates suggesting a million or more on Monday, June 15. Their numbers and their diverse origins belied the thought that this was merely sour grapes from an isolated group, disappointed that the result had gone against them. European and U.S. news media reported excitedly that these were the biggest demonstrations in Iran since the revolution. In the evenings, Iranians gathered on rooftops to shout "Allahu Akbar!" as they had in 1978–79.

Over the first weekend of demonstrations, Ahmadinejad referred to the demonstrators as "Khas o Khashak" – dust and trash, or flotsam and jetsam, that would be swept away. But the demonstrations did not go away. Despite beatings and arrests, and despite efforts by the regime to prevent any reporting of the protests, they continued, and Iranians found ways to get reporting out of Iran, including through new internet channels like Facebook and Twitter. Several reports indicated that the hardliners themselves were unnerved by the demonstrations. One (derived from a U.S. diplomatic telegram via Wikileaks) suggested that at a high-level meeting Ahmadinejad himself said that the people felt suffocated, and there should be greater personal and social freedoms, including freedom of the press. Angered by this, the Sepah commander Mohammad Ali Jafari responded: "You are wrong! It is YOU who created this mess! And now you say give more freedom to the press!" According to the source, Jafari then slapped Ahmadinejad in the face, causing an uproar in the meeting. Others suggested later in the year that Khamenei had an aircraft overhauled to ensure it was in good readiness to fly him out of the country at short notice, though the reliability of this story was doubtful.

The ruling clique responded to the outcry, the demonstrations and the accusations of an electoral coup by alleging an attempted coup by the other side – saying that the regime had foiled a Western-backed attempt to overthrow the Islamic republic, along the lines of the Velvet Revolution of 1989 in Czechoslovakia, the Rose Revolution of 2003 in Georgia or the Orange Revolution of 2004/05 in Ukraine. They declared that the instigators of this new Velvet Revolution were, of course, the U.S. and Britain. To support the story, the MOIS arrested several Iranians working at the British embassy, all of whom were eventually released.

On the evening of June 20, a young woman called Neda Agha-Soltan got out of her car, which was obstructed by the protesting crowds around Kargar Avenue in Amirabad in north-central Tehran, to escape the heat. She was accompanied by her middle-aged music teacher. Soon afterwards, she was shot in the chest and despite the efforts of those around her, including a doctor, to staunch the flow of blood, she was dead within a few minutes. Bystanders filmed the event on mobile telephones, and the images went around the world on YouTube. Neda became a symbol of the protests and of the brutality of the regime’s conduct (their spokesmen later tried to claim that she had been shot by the CIA or other foreigners). Despite the dwindling of the street protests in later weeks, under pressure from the police and the Basij militia, demonstrators turned out again in large numbers on July 30, the fortieth day after her death, to protest against the shooting. There were demonstrations again on September 18, when the regime attempted to hold its usual event (Qods day – Jerusalem day) to show support for the Palestinians against Israel. Opposition demonstrators, making use of the fact that the color used to symbolize the Palestinian cause, like that of the Musavi campaign, was green, appeared again en masse, took over the event and shouted down the official slogans.

The demonstrators pulled off a similar trick on November 4, when they took over the official event to mark thirty years since the occupation of the U.S. embassy in 1979. Thousands of protestors appeared in Tehran, defying arrest by the police and the Basij, and there were similar manifestations in Isfahan, Rasht, Shiraz and Tabriz. Instead of the weary regime mantra of "marg bar Amrika" ("death to America") some called instead "marg bar hichkas" – "death to nobody."

Through the summer and autumn ugly stories spread of the torture and death of protestors in custody. Estimates of the number of deaths mounted to several hundred. At the end of July the supreme leader ordered the closure of the Kahrizak detention center after protests about torture, and the death of Mohsen Ruholamini, the son of a prominent conservative politician. In November a young doctor, Ramin Pourandarzjani, who had seen Ruholamini shortly before his death and had been pressurized to say that he had died of meningitis, himself died in suspicious circumstances at Tehran police headquarters.

Some Western commentators said or wrote that the outcome of the elections was immaterial because there was little to choose between the policy intentions of the two main protagonists, Musavi and Ahmadinejad. That missed the point. Musavi and his reformist supporters were not looking to overturn the Islamic republic, but what had happened was no less important for the fact that they were not following a Western-inspired agenda. By falsifying the election results (as was widely believed to have happened), the regime had gone much further than ever before in subverting the representative element in the Iranian constitution and had precipitated a crisis over the very nature of the Islamic republic. Important figures like former presidents Rafsanjani and Khatami were openly critical of what had happened. Opposition candidates Musavi and Karrubi refused to be silenced. Khamenei was forced to take a more partisan position than ever before, abandoning the notion that his office put him above day-to-day politics. The demonstrators rewarded him with the chant "marg bar diktatur" ("death to the dictator"). His position was weakened.

Ever since the revolution, the Islamic principle and the constitutional, republican, democratic principle had worked uneasily together, and from early on the democratic element had been eroded. But after June 12 those who had cherished the representative strand, who had believed that had been one of the achievements of the revolution, and that its survival gave some hope for renewal and peaceful change, were faced with the bald fact that it had been snatched away. They were now being ruled under the threat of naked force, by a ruling group who had abandoned Khomeini’s principle of balancing opposing forces under a regime umbrella, and whose claim to Islamic legitimacy had worn very thin. Several leading clerics were critical of the conduct of the elections, and others stayed pointedly silent. The crisis was not just a confrontation between the regime and a section of the populace; it was also a crisis within the regime itself, and it is still not resolved.

In the meantime, the regime continued to blame Western governments for instigating the demonstrations, presenting the Obama administration with a sharpened dilemma: should America pursue its policy of détente with a regime that had just, in the judgement of many of its own citizens, stolen an election in such a bare-faced manner? The logic of engagement with Iran had not depended upon the virtue or otherwise of the Iranian regime, and cautious attempts to engage with the Iranians continued. But revelations in the autumn that showed that the Iranian government had been constructing a further uranium-enrichment facility near Qom and was conducting new missile tests increased the pressure for new sanctions. The Obama administration seem to have concluded that their attempt at a reconciliation with Iran had been a failure, whereas in fact it had put the Iranian regime under greater pressure, more effectively, than thirty years of sanctions, and had helped to precipitate the biggest challenge to those controlling the regime since the revolution. But Obama was subject to his own political pressures. From the autumn of 2009 Hillary Clinton became more prominent in the presentation of U.S. policy toward Iran, which returned to the usual barren pattern of admonitions and exhortations familiar from earlier U.S. administrations, and the grinding process of cranking out ever more restrictive sanctions measures.

The elections and their aftermath further strengthened the position of the Sepah. Ahmadinejad’s debt to them was well known, and there were many reports (as in 2005) of their engagement in the election campaign in his interest – though the firmness of their commitment to him was less clear. The regime’s dependence on them to face down opposition and keep the ruling group in power was only intensified by the outcome of June 12. The role of the Revolutionary Guards in every aspect of Iranian life, and especially in the economy, had been increasing and strengthening for many years. It was emphasized further in October 2009, when a company linked to the Sepah paid the equivalent of $8 billion for a controlling share in the state telecommunications monopoly. The country was looking more and more like a military dictatorship – a tighter and more effective version of what the revolution had brought down in 1979. After the June 12 elections, Ayatollah Montazeri commented, "What we have is not Islamic republic, but military republic." The prominence of Montazeri and some other clerics in the opposition was another significant phenomenon in the aftermath of June 12. One of them, Yusef Sanei, a reform-inclined moderate and a marja for many religious Iranians, had denounced the elections as illegitimate. Regime-oriented clerics attempted to begin proceedings to remove his status as marja-e taqlid (recalling the way Shariatmadari had been treated in 1982) but others resisted them on his behalf.

Montazeri died in his sleep at the age of eighty-seven on December 19, 2009. There were further demonstrations associated with his funeral in Qom on December 21, and pro-regime thugs attacked Musavi and Karrubi there in the street. There were further demonstrations on December 27, the day of Ashura, in Kermanshah, Isfahan, Najafabad and Shiraz as well as in Tehran; opposition demonstrators were again attacked, and Musavi’s nephew was shot and killed:

By noon, Tehran was practically ablaze with clashes. There were unprecedented numbers in the huge crowds of opposition supporters and people were confronting the regime’s forces with more intensity than ever before. The clashes reached their peak in Vali Asr Square when the crowd seized a police kiosk and were met with extreme ferocity when the police drove a car straight into the throngs, running people over in front of everyone.

The opposition’s practice of using familiar dates in the calendar to take over official events was countered by the regime on February 11, 2010 (the anniversary of the final triumph of the revolution in 1979) by closing down Internet servers and mobile phone networks, and by closing off access to Azadi Square by all but pro-regime supporters bused in from outside. That attempt was the last for some time by the opposition to express their continuing disapproval of the regime on the streets. They tried again on February 14, 2011 – again the regime’s tactics of flooding the streets with police and Basij, preventing small groups from coalescing into larger ones, and closing down telephone and Internet communications, proved effective. But the hardline leadership were apparently scared enough this time to take Musavi and Karrubi into house arrest, where at the time of writing they remain. Large numbers of reformists, politicians, journalists and others have left the country and gone into exile since June 2009 (including Mohsen Makhmalbaf, Shirin Ebadi and Ataollah Mohajerani), and an unknown further number are still in prison (including the film maker Jafar Panahi, director of "The Circle" and "Crimson Gold"). A new low point was reached in the summer of 2011, when, after the death of the veteran liberal-nationalist Ezzatollah Sahabi, his daughter Haleh was assaulted by Basijis at his funeral and died shortly afterwards of a heart attack.

Totalitarian or Democratic? Or Neither?

Since 1979, despite much speculation and many predictions at different times of the imminent demise of the Islamic republic, despite the vicious eight-year war and various other attempts at regime change along the way, the Islamic republic has survived and has proved more stable than expected. It is not fanciful to make a connection between this stability and the fact that the republic is an Islamic republic, unlike the anti-clerical or secular regimes set up by the French and Russian revolutions, for example. Islam has given the regime deeper ideological roots in Iranian society than the innovative ideologies of the Jacobins and Bolsheviks achieved (ideologies that most of the mass of the French and Russian populations probably never understood). Islam could have sustained a more liberal, democratic regime; instead it has been used to sustain a less liberal, more autocratic form of government (albeit with democratic elements that are still significant, though in retreat). Islam is a more serious idea than Jacobinism or Marxism: it is more embedded in people’s lives than those political ideas ever became; in the cultural/intellectual race, it has longer legs.

But those at the top of the regime run a risk – a known risk that people have been pointing out ever since 1979. Shi‘ism more than any other form of Islam is traditionally, acutely, almost obsessively sensitive to the abuse of political power. Islam still works as a support to the regime because a significant portion of the population still accept its Islamic credentials. But when innocents are beaten up, tortured and shot for asking what has happened to their vote, and when peaceful funerals are broken up by club-wielding thugs, the risk run by the regime intensifies. An example of this is a statement by the young Basiji who witnessed abuse and rape of prisoners arrested after June 12, who told a Western reporter: "now I am ashamed in front of people . . . and I am ashamed in front of my religion."

Islam is not susceptible to the control of the regime in the way that Jacobinism and Marxism were – it is an independent standard, which is ultimately beyond the reach of the regime. No one owns the church. If a critical mass of believers among the Iranian people ever decide that the Islamic regime has become un-Islamic; if they begin to call it the rule of Yazid, as they did the government of the Shah, then Iran’s rulers will be gone as if they had never been more substantial than a puff of smoke.

What do we in the West want to happen in Iran? Broadly, we want the Iranians to have a free democracy, for Iran to normalize her external relations with the U.S. and other Western countries, to end whatever plans she may have for developing a nuclear weapon, to recognize Israel and stop funding Hamas and Hezbollah – to become what we would regard as a normal country. To come back into the international fold, to stop being a problem. The events of June 2009, when large numbers of Iranians demonstrated for their Green movement and against the re-election of President Ahmadinejad in what they believed to be an electoral fraud, indicated that many Iranians, perhaps a majority, think more or less the same way, on many of those points at least. But they did not get their way, and there is no sign that they will get their way in the immediate future. Why did they not succeed?

Some of the complexities, paradoxes and incomprehensibilities of Iranian behavior are hard to grasp, even for those with an understanding of the events covered in this book. Some of the complexities are intractable, and it is a feature of contemporary comment on Iran that subjectivity tends to reassert itself over objectivity. Our response to Iran says as much about ourselves as about Iran. When struggling to assess what may happen, we tend to betray what we want to happen. And our problems with Iran to some extent reflect problems with our own, Western model of development.

Comparisons are sometimes made between contemporary Iran and the former Soviet Union. Is Iran the Soviet Union of the twenty-first century? No . . . and yes. Taken strategically, the comparison is dangerously misleading (and unfortunately, for various reasons, there are some who are ready to mislead, and to be misled). Iran is not a threat to the West in any remotely comparable way. Iran may be on the point of acquiring a nuclear weapon, but it does not have, and will never have the global strategic reach of the former Soviet Union, nor the offensive military power in conventional forces to back it up, nor the defense spending (as noted already above), nor the military-industrial complex, nor the military occupation of half a continent, nor the totalizing grip on the thought of its own population. Neither Stalin nor Brezhnev would have tolerated Musavi, nor demonstrations on the scale achieved by the Green movement. They would have sent in the tanks, as in 1956 in Budapest and 1968 in Prague.

The Iranian regime has been reluctant to use the full force available to it against demonstrators. The events of the Arab Spring of 2011 and since have provided a comparison for this (some Iranians have claimed that the demonstrations of the Green movement, and their innovative use of new technologies, were the precursors of and the inspiration for what happened in Tunisia and Egypt). The Iranian regime has used brutality, but it has not gone to war with its own people like Gaddafi in Libya or the Assad regime in Syria. For a long time, Musavi and Karrubi were allowed to stay at large, speaking out against what had happened. The regime still wanted to maintain its own myth of democracy. When he came under pressure, Khamenei closed down Kahrizak. The origins of the regime in popular struggle against tyranny still act as a restraining factor, albeit ever more feebly. Despite the regime’s success in putting down the opposition, its response still looks more like Egypt in 2011 than Syria in 2011–12 (at the time this book went to print in the latter part of 2012, the Iranian regime was maintaining its firm support for the increasingly embattled and increasingly vicious Assad regime). So there is still uncertainty about how far the regime will go in its repression, and whether its security instruments will obey it if it goes too far. Some have questioned why overthrow of the regime in Iran did not follow on from the overthrow of other regimes in the Middle East in 2011 – that may yet happen, but the crushing effect of the repression, imprisonments and exiles that followed the events of 2009 is for now a sufficient answer.

The nuclear weapon program is a concern, but Iran would never use a nuclear weapon against Israel or anyone else in a first strike. Like the states that have nuclear weapons already, it wants a nuclear weapon as a deterrent; its geographical position and history would be argument enough to justify that, if it were not for the treaty commitments Iran has made not to acquire nuclear weapons. In addition, where the Soviet Union represented an ideology that was persuasive to some within Western societies, and stood for one side of a debate or conflict within Western democracy itself, Iran’s Islamic ideology has no such purchase within Western society. Some might argue that Islamists are indeed active in Western society; but they are active only within communities of Muslims, mainly immigrants. The general appeal of their views is limited and small; their views do not form one end of a continuum of political debate as Soviet-aligned communism in Western society used to do. Iran’s attachment to the minority, Shi‘a side of the Muslim schism further limits her ideological reach.

Does Iran, like the former Soviet Union, interfere in neighboring countries and attempt to spread its revolution? Yes . . . and no. The present regimes in Afghanistan and Iraq, perhaps best called proto-democratic and supported by the U.S. and the West, are pro-Iranian and were set up with Iranian help. As we have seen, Iranian involvement in the insurgency in Iraq became something of a chestnut between 2003 and 2009 as some tried to blame Iran for the Western coalition’s difficulties, but there was much more evidence for the destabilizing effect of support for insurgency originating in Saudi Arabia, which tended to be ignored. Similarly now in Afghanistan. For the most part, Iranian rhetoric about exporting revolution did not survive the earlier phases of the Iran–Iraq War, and the Shi‘a Crescent theory, of a threat of Iranian-backed revolt by the Shi‘a underclasses of the Persian Gulf region, is bunk (despite its enthusiastic espousal by Tony Blair, in his unconvincing role as Middle East peace envoy). Iran has interests and associates in both Iraq and Afghanistan, and the interests, like the borders, are permanent (unlike, perhaps, those of the U.S. and her allies). Iran does not like the heavy U.S. and allied military presence so close to its borders. Though largely unproven, there probably has been covert Iranian involvement in both Iraq and Afghanistan. But the closer to Iran’s borders, the more pragmatic Iran’s foreign and security policy has been. The stated Iranian policy towards both Iraq and Afghanistan has been to foster stability in both, and it is a serious failure of Western (and Iranian) diplomacy that we have been unable to make better use of the strong alignment of interests between ourselves and the Iranians.

On a minor scale, the comparison between Iran and the Soviet Union is more apt. Opposition to the U.S. is a fundamental ideological tenet of the Iranian regime, and the enmity and supposed interference of the U.S. is used to justify internal repression. As in the former Soviet Union, the ideology has become fatigued and the ruling clique increasingly uses its security apparatus to uphold its dwindling authority. There are other similarities. In his book "Living in Truth" Vaclav Havel described the debilitating effect of living in a society like that of Czechoslovakia under communism, in which dishonesty and lies were necessary for survival and essential for preferment, entering the soul and creating a kind of moral anomie. Azar Nafisi (author of "Reading Lolita in Tehran") and others have described a similar effect in the Islamic republic, where the dishonest nature of the regime and compromise with it is made more dismal by the unemployment that keeps many Iranians, especially young Iranians, in a limbo of desperate inactivity and disappointed ambitions, and induces others to do a deal with the regime.

And yet . . . Sartre once wrote that the French were never so free as they were under Nazi occupation, in the sense that moral choice and the pressing seriousness of consequences were never so sharp as they were at that time. That too is true in Iran. In many Western countries, for many of us, we have it easy and have become morally lazy, relativistic and cynical. In Iran, the essentials of right and wrong, freedom and repression have been everyday matters of discussion and choice. This moral earnestness emerges in some Iranian cinema. One outcome of the furore over the 2009 elections was that the authority of the supreme leader, once taboo, now came openly into question. The field of debate, under repression, actually widened – at least in that area.

Is Iran a democracy? We are probably too ready to dismiss democracies for not being perfect – for example some said Britain was no longer a democracy after the invasion of Iraq in 2003 because large numbers had demonstrated against the invasion, and opinion polls suggested a majority opposed it. Democracy has some categorical attributes. Firstly, it needs a democratic constitution. Iran has that, at least potentially; it is flouted and manipulated by the regime in many respects, but elections have been held regularly, politicians have accepted loss of office and government has proceeded without coups d’état (albeit with a question mark over the events of June 2009). More importantly, it needs a democratic people, in other words, a people who believe in or aspire to democracy. Iran has that too, as the Green movement has demonstrated, and Khatami’s reform movement before that. If democracy is most alive where people are most willing to struggle, suffer and even die for it, then the events of 2009 showed democracy alive and vigorous in Iran. Some have suggested that this is the most important aspect of the events of 2009 – that they marked the renewal of the Iranian people’s commitment to the principles of democracy and freedom. But a functioning democracy, in which the will of the people is expressed through elections and determines the nature of the ruling government – no, Iran does not yet have that.

Postscript

A series of events over the autumn of 2011 and the winter of 2011/12 again increased tension between Iran and the West, seemingly bringing closer the threat of war, as had happened four years earlier, under the Bush administration. In October 2011 it was alleged on the basis of an FBI investigation that Iran had inspired a plot to murder the Saudi ambassador to the U.S. in Washington (the same ambassador who had, according to Wikileaks, earlier urged U.S. military action against Iran – to "cut the head off the snake"). Although some of those involved in the alleged plot seemed unlikely characters, and despite the fact that the director of the FBI commented at a press conference that the allegations sounded like a Hollywood film script, the Obama administration seemed to take the story as already proven, blamed the highest levels of the Iranian regime, and announced that new sanctions would be applied. A few weeks later, on November 8, the IAEA issued a new report on Iran’s nuclear program, which went into greater detail than ever before about suspicions that Iran was pursuing a nuclear weapon (drawing on information from Western intelligence agencies), but had little or no evidence to suggest that significant weapon development had gone forward since 2003 (seeming therefore to confirm the NIE of November 2007 on that point). But the report was much trumpeted before release, by Israeli and hawkish U.S. commentators, as conclusive proof of Iranian misdoings. It looked rather as though the timing of these events had been coordinated as a new initiative to increase pressure on the Iranian regime. Certainly, the U.S. and the West had the initiative in these months, where previously Ahmadinejad had been the one setting the agenda. There was renewed talk of military action against Iran, and of further rounds of sanctions. In mid-November the U.K. announced that (following the IAEA report) Iran would no longer be allowed access to British banking institutions, as part of what was hoped to be concerted international action. On November 29 police stood by while a mob of Basijis and alleged students broke into the British embassy compound in Tehran, ransacking staff accommodation and looting and destroying property. In the aftermath the U.K. withdrew her diplomats from Iran and expelled all the Iranian diplomats in London. Other Western countries also withdrew their ambassadors from Iran. In January 2012 the E.U. announced an oil embargo, to take effect from July. Over this period, there were several assassinations in Iran of people associated with the nuclear program; the assassinations were widely believed to have been instigated by Mossad. A U.S. unmanned aircraft crashed on Iranian territory in the east, near the border with Afghanistan; the Iranians refused to return it.

There was much discussion and comment at this time in the Western media about more sanctions and the threat of military action – but also a growing number of voices questioning Western policy and the apparent drift toward war. There was a sense that greater pressure was being applied to Iran partly because policy-makers no longer knew what else to do, and because the process of securing international agreement to new sanctions measures in the U.N. Security Council had acquired its own momentum. New sanctions measures had become a way to deflect pressure from Israel, as figures within the Israeli government spoke more insistently about the likelihood of Israel taking military action against the Iranian nuclear program. As the tension escalated, so too did the risk of miscalculation and war by accident.

Despite the new sanctions measures and increasing financial pressure, the Iranian regime remained defiant, resting on the conviction among the Iranian people, discussed in earlier chapters, hardened in the fires of the revolution and the Iran–Iraq War, that Iran would never again be bullied or humiliated by foreign powers. It would be a mistake to underestimate that determination to uphold national independence. Some doubted the wisdom of applying pressure to Iranian oil supplies. Whatever the other effects, an oil embargo would raise oil prices, at a time when the world economy, and especially the European economy, was vulnerable and weak. Two of the countries in Europe that were financially and economically most vulnerable, Italy and Greece, were also among those most dependent on Iranian oil, with refining infrastructure least capable of switching to other suppliers.

In this developing crisis, some of the essential elements of the problem remained somewhat vague and unfocused in the debates that went on. In Israel, the government of Benjamin Netanyahu maintained its account of the situation at a high pitch, accusing the Iranian regime of being aggressive, expansionist and irrational. It claimed that the possibility of an Iranian nuclear weapon was an existential threat to the state of Israel. Notwithstanding that some irresponsible voices from within Iran had made statements that played into this interpretation, this line was exaggerated and irresponsible in itself. Most knowledgeable observers accepted that, even if Iran acquired a nuclear weapon, it would never be used against Israel in a first strike, or at all unless Iran itself were attacked, because the retaliation from the US and Israel would be so overwhelming. This view was reinforced by statements from within Israel – from Meir Dagan, former Mossad chief, and from Yuval Diskin, a former head of the Israeli Shin Bet (internal intelligence – counterpart to MI5), in March and April 2012 respectively. The statements came shortly after a visit to Washington by Benjamin Netanyahu, in the course of which Netanyahu failed to persuade President Obama to accept a position on Iran that said that an Iranian threshold capability was in itself an unacceptable red line (Diskin accused Netanyahu of having misled the Israeli public with his dramatization of the threat from Iran). The threat to Israeli security interests was real and genuine, but what was threatened was the loss of the Israeli nuclear monopoly in the Middle East and the weakening of the Israelis’ own (undeclared) nuclear deterrent – a serious matter, but not immediately apocalyptic. The supposed and oft-mentioned threat of an arms race in the Middle East was something of a chimera – Israel’s possession of a nuclear weapon had not prompted Saudi Arabia, for example, to acquire one. Another peculiarity was that the sanctions were all primarily directed at getting the Iranians to suspend their uranium enrichment activity – but that activity had by 2012 been running long enough and had developed to a point at which continuing enrichment seemed rather immaterial. More important than the actual uranium was the understanding of the enrichment process and the confident know-how the Iranians had acquired. Essentially, what the U.S. and the E.U. were trying to do was to reverse the Iranian intention to develop a nuclear weapon. But the Iranians themselves continued to deny any such intention, and the evidence seemed still to indicate that substantial progress toward their nuclear weapon had halted in 2003. How would we know, beyond what we already knew, if we were to succeed in reversing this Iranian intention?

Some suggested that these and other ambiguities in the Western position indicated that the real Western objective was not resolution of the nuclear problem, but regime change in Iran – a situation reminiscent of a similar dangerous ambiguity before the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003. An ambiguity that went some way to legitimate the resistance of the Iranian regime, and which objectively might be regarded – for example in the context of the clause in the NPT permitting a state to withdraw from the treaty if it considered itself to be under a serious security threat – as just cause for the Iranian regime to want a nuclear weapon after all.

It became apparent over the first half of 2012, as new negotiations on the nuclear problem unfolded in successive rounds in Istanbul, Baghdad and Moscow, that the Iranian side was negotiating with a greater degree of seriousness and application than in previous talks. In particular, the Iranian negotiators had a clearer and more direct mandate to speak with the full backing of the supreme leader than had been the case previously. Spoiling statements by Ahmadinejad, a feature of earlier talks, were conspicuous by their absence. The greater seriousness from the Iranian side may have reflected a perception on their part that these talks, with a more prominent and more serious level of U.S. participation than ever before, in turn merited more concentrated attention from them too. Alternatively, they may have judged that they had secured most if not all of what they had intended in the way of progress with enrichment, and it was time to make a settlement and bank those achievements. Or (as many assumed) it may be that they were keen to see the new, tougher sanctions measures removed. Insistence that this should happen was certainly a prominent feature of the Iranian negotiating position in Istanbul, Baghdad and Moscow. In fact, it was most likely a combination of all these factors.

Strangely however, the U.S. side at the Moscow talks seemed at one point to say that whatever concessions the Iranian side made in the talks, the sanctions could not be lifted (reflecting the institutional inertia of the sanctions process in the U.S. Congress, the U.N. and the E.U.). It appeared that the U.S. and the West expected not to negotiate, to make concessions in exchange for concessions (as is normal in diplomacy and negotiations of any kind), but to deliver an ultimatum and dictate a settlement. It is hard to imagine any government, except under the most extreme duress, capitulating to such a demand, and it was no surprise that the talks did not prosper. But they did continue – neither side wanted to break off. In fact, however Western governments presented the state of the talks, the real question was when and how the U.S. (with Israel muttering dark threats in the background) would be prepared to come off their previous position of no enrichment, and accept the fait accompli of the Iranian enrichment capability – albeit at a low level (3–5 percent) and with tougher inspection safeguards. The parameters of the deal that was in the offing were fairly plain – but it was plain too that the Obama administration, in the run-up to a presidential election in November 2012, was not in a position to seal that deal.

In the meantime, the assassinations of Iranian scientists, assumed to have been perpetrated by the Israelis, appeared to receive a response in incidents in Georgia and Delhi. In the latter case a car belonging to the Israeli embassy was targeted on February 13, 2012 with a magnetic bomb delivered by an assailant on a motorbike (the method resembling that used in the attacks in Iran), and four people were injured. The Delhi police said they believed there was a connection with the Sepah, though doubts were raised about this later. Then on July 18, a bomb exploded next to a tourist bus carrying an Israeli tour group at Burgas airport in Bulgaria, killing five Israelis, a Bulgarian bus driver and the man carrying the bomb. Initially the local authorities assumed it had been a suicide attack, but later it emerged that the bomb had probably been detonated remotely. There appeared to be a connection with Lebanese Hezbollah. Responsibility for all these incidents remained unclear, but they contributed to the general air of tension, and together threatened to escalate, and to displace what fragile grounds for optimism remained in the continuing talks.

Amid this uncertainty and complexity, some firm realities stand out. The question of an Iranian nuclear weapon is an unwelcome extra problem in the Middle East, and potentially a dangerous one. But it is inextricably tied in with the long-running hostility between the U.S. and Iran, and between Iran and Israel. The nuclear weapon’s only purpose is deterrence – in this case as an instrument to bolster Iran’s hard-won independence and the survival of the Iranian regime. If there were no hostility, or if the level of hostility could be reduced and made safe, the threat and the need for deterrence would also be reduced. The fundamental problem is that hostility and the need to resolve it – easier said than done, of course. But it is perhaps relatively easy, notwithstanding the history, the harshness of the rhetoric, the intransigence, the failures of understanding and imagination on both sides, and the vested interests some have on both sides in the continuation of the hostility. Relatively easy because this dispute lacks many of the features that make other longstanding international crises and problems intractable. The three states most deeply involved, Iran, the U.S. and Israel, share no mutual borders. There are no border disputes or territorial claims. There are no refugees demanding the right to return. There is no intercommunal violence. Within quite recent memory the peoples involved have been allies, and even today there is no deep-seated hatred between them – for the most part, indeed, rather the reverse. When Obama made a serious attempt at reconciliation in the first six months of his administration, the response from ordinary Iranians was such that it helped to produce the Iranian regime’s most serious crisis since 1979. Far from failing, the reconciliation effort worked more dramatically than anyone could have imagined. But then it was abandoned. It needs to be resumed, reinforced, and maintained with determination until it succeeds.

Reprinted from "Revolutionary Iran" by Michael Axworthy with permission from Oxford University Press USA. Copyright 2013 Oxford University Press USA and published by Oxford University Press USA. (www.oup.com/us). All rights reserved.

Shares