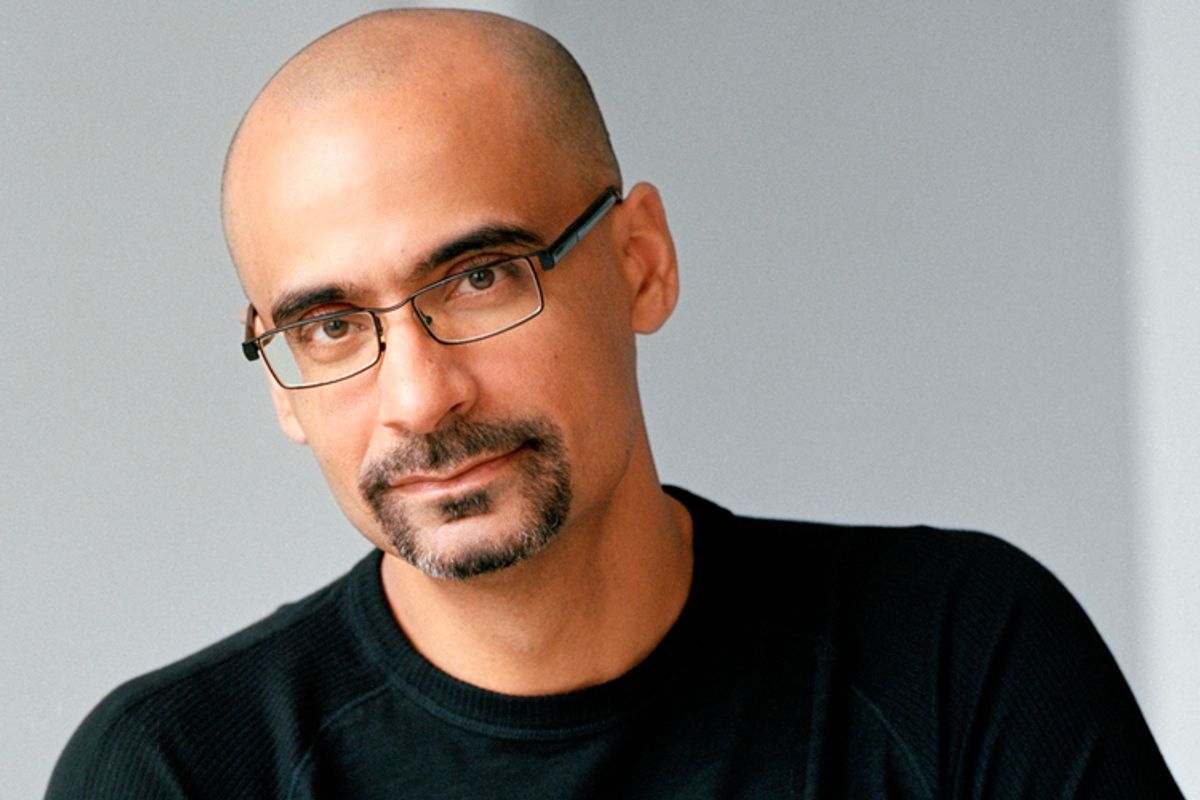

My first encounter with Junot Díaz was brief and wondrous. I was grabbing lunch with a few classmates at a hole in the wall in the East Village when I spotted him hunched over a plate of shawarma. Like the rest of the country, I had been dazzled by his Pulitzer-winning "Oscar Wao" -- its eponymous character but especially its narrator, Yunior, Díaz's literary döppelganger -- and so despite myself, I hazarded an "Excuse me, are you Junot?"

That was all it took.

"What's going on, young people!?" His exuberance was so infectious I came this close to answering "falafels, yo!" (I resisted, mercifully). Before my friends realized what was happening, he was peppering us with questions about where we were from, what we were studying, what we wanted to do. He was a dude, and he was cool -- far cooler than he had any reason to be with a group of strangers in a Middle Eastern dive on a dreary winter afternoon. Mostly he sounded exactly like the effervescent narrator of his fiction, Yunior made flesh.

I was reminded of this run-in when I found him trembling very slightly beside a sculpture of a golden sea urchin in the lobby of the SoHo Trump hotel earlier this month. Díaz blamed his inability to sit down on severe back problems. Yunior, the protagonist of his latest short story collection about a "scumbag cheater," suffers from stenosis and a numbing sensation in his arms and legs. And yet despite these many parallels, Díaz would be the first to admit that he both is and is not the hero of his short stories. "The same way you're a complex person when you read," he says, "I'm a complex person when I write."

It's this tension in part that makes "This is How You Lose Her," like "Drown" and "The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao" before it, so readable. You're never entirely sure if you're being conned by Yunior or Junot, neither or both. His fiction also explains why the debate over "likable characters" is not only absurd but destructive; it demeans the author's creation and insults the reader's intelligence.

Despite his obvious discomfort, Díaz gamely spoke to Salon at length about how his fiction is as indebted to the Wu Tang Clan as it is to writers like William Gibson and Toni Morrison, and why our favorite books tell us only so much about their authors.

Race is obviously one of the central themes of your fiction, whether it’s handled comically in a story like “The Cheater’s Guide to Love” or more often tragicomically in stories like “How to Date a Brown Girl.” I was wondering what you make of the debate about cultural appropriation Miley Cyrus has incited.

As a country, we’re addicted to our consumptions. Among our primary consumptions are images of black bodies as being hip, as being renegade, as being kinda fucking dangerous, even if they’re malign imaginaries. It’s something that’s been in circulation for a long time. What I think is incredibly fascinating is that this is occurring while the president is pushing a war. Nothing could be more perfect about where we’re at on an ethical level, nationally. Had I written this up in some sort of Dickensian attempt to lacerate American culture, people would be like, “Oh, this is too absurdly pat.”

The Onion really nailed it.

Oh, I didn’t see the Onion article!

It was a fake letter from the editor of CNN.com explaining why they chose to lead with the story.

I love the Onion. Seamus Heaney just died, and one of the great obituaries of him was a wonderful quote he had about being on the side of undeceiving. And I always thought that something like the Onion is the deceiver that undeceives, which is what fiction at its best attempts to do.

A few months back, Claire Messud lit into a Publishers Weekly interviewer for suggesting the protagonist of her latest novel wasn’t especially likable. She argued that we’d never question whether we like Raskolnikov or any of Jonathan Franzen’s characters or even Oscar Wao. Does she have a point?

I’m going from hearsay here, but I can imagine the sort of umbrage she took. There’s a profound trivialization of literature in the way that it is used and, yes, if you’re a woman or a person of color, there are certain biases that are built in. There’s no fucking question.

But I get people saying “I don’t like Yunior” or “I don’t like Oscar” all the time. When people say that to me, I always remind them that in the same way that I’m a more complex person when I write, you’re a more complex person when you read. The real question for me as the writer is why you’re friends with the people you’re friends with. Most of us are friends with people we don’t like, so what’s the big deal? We’re used to hanging out with people we don’t like, so this should be a familiar feeling.

Returning to Franzen, in an interview with Vice you said “a writer like Franzen, with each coming generation, is more and more absurd and more and more exactly what he is.” What did you mean by that?

My point was that in a country that has become so extraordinarily diverse, we still imagine a white writer as the universal writer – and that absurdity is becoming almost unsustainable. I visit high schools all the time. When I look at the kids that are coming up, they look nothing like the writers that we’re all running around calling the voice of this country. Despite what we would like to think, the lag time between what a culture recognizes as its country and what the country is, my brother, is quite extraordinary. Outside of a few strains, I feel like the literary apparatus still thinks of this country very much in the 1950s.

Do you see any parallels between publishing and academia?

Oh, yeah. We must understand that power and privilege tend to hew to each other. Just look at how long it took for MIT to start granting tenure to women – white women! But look, I emigrated to this country. If anything prepared me for a place like MIT or a place like publishing, it was being an immigrant from an illegal parent, trying to enter American society. Jersey prepped me real good.

In an interview with the Rumpus, you said you thought the linked story collection could capture certain aspects of the human experience better than a novel or an anthology. There’s a clear narrative arc from the first to the last stories of “This Is How You Lose Her.” Do you ever worry about readers consuming your fiction out of order?

There are many other easier ways to write books, but I am deeply attracted to the game of collaboration. When you write a collection like this, it permits your reader to create their own books in ways that I don’t think a novel necessarily can. So I don’t mind at all. I have readers that put together books that are wildly different than the ones that I imagined. And it’s that distance that makes me feel like I’ve done my work correctly. When I see that difference and disparity, that’s when I can say I’ve given enough material for readers not only to build their own cathedrals, but something entirely unique if they wish.

In that same interview, you also mentioned you used to be embarrassed about being a slow writer.

I wasn’t just a little embarrassed. I have to say I felt shame about it. Typical good immigrant kid – if you’re not doing the work, you should feel ashamed.

Has the recognition you’ve received helped you let go of that?

I don’t think it was the awards. I’m fucking 45, and I just don’t have the same energy to be as neurotic. You have to put triage on your injuries. I really wearied myself into acceptance -- I just kinda got tired of hating myself for it.

You’re conspicuously absent on Twitter. I actually find it refreshing, but I was wondering if there was a reason behind that.

I’m already fucking half nuts. I think anything that’s good about my writing comes from my resisting my desire for attention and approval. I can write shit that risks my readership, and the one thing that I know is that my readership is predominantly female. When I decided to finish this book about a real fucked-up scumbag cheater, I still remember the early notes I got back from my female friends when the book was done like, “Dude, you need to game it a little bit, make the female characters less from his selfish, narcissistic point of view.”

Can you envision yourself ever leaving Yunior’s universe?

I think hopefully my next book won’t be about him. We’ll see. The dream – when I used to have a dream of productivity – would be that I’d write a few books about him, and write a few books about some other shit. But right now I don’t know. I’m like that dude who can’t even promise his kids breakfast right now.

“Monstro,” at least in part, is an apocalypse novel about the spread of an infectious disease that originates in Haiti. Why do you think sci-fi is enjoying such a renaissance right now? It seems like there’s an entire wave of literary authors resurrecting the genre, Jonathan Lethem and Colson Whitehead to name a few.

I’m sure the answer is very complex, but I’ll tell you one thing: A lot of artists are figuring out how to make fucking money. I’m not saying that’s what these cats are doing – Lethem’s been in the game from the beginning. He started out as a hardcore genre writer and became a literary writer. But ultimately, I think it’s a matter of privilege. Literary writers can attack new markets without ever losing their cachet as literary writers. I don’t think that tide has raised the boats of genre writers. A literary writer who writes a sci-fi novel will get a fucking Guggenheim. A genre writer who is classically genre, writing a genre book, will not get a fucking Guggenheim.

I’m less interested in a kind of artistic zeitgeist as much as I am in IPE, international political economy. If there were no money to be made from genre, would anyone be doing this? Part of my interest in doing a genre book was actually to put that question front and center. Because the funny thing about being a person of color is you’re already being considered a fucking genre, you know? Or better yet, you’re already being considered science fiction.

Have you been following any of the drama surrounding the adaptation of “Ender’s Game”?

This is the problem with thinking you know your artists. If you read more of Orson Scott Card’s work, it becomes clearer. But if you just read “Ender’s Game,” and you read Orson Scott Card’s comments -- you can’t square them, man.

It seems like he says something awful every few months.

He can’t stop. This is someone who’s clearly addicted to the negative attention. He’s like the opposite of the monster that always needs to be fed. But this is why we’re so fascinating. We’re far more complex than reading and writing. Orson Scott Card is a cretinous fool in his political life, and yet when he wrote this one book, something else came together. So wild.

You grew up in New Jersey and you’ve been outspoken about your progressivism. What do you think of Cory Booker’s candidacy?

I mean, the guy’s a superstar. On paper, he seems to be much more humane than our president is, certainly when you consider our president’s deportation policies. I wouldn’t think Cory Booker would endorse something like that, but you never know. The gap between what we need from our political leaderships and what one must be to be a politician has never been wider. If we don’t get a new political order, we’re going to keep finding ourselves in this same situation.

But let’s not front, Hillary Clinton and him as vice-president? It would be a fucking wrap. It’s not like Hillary needs to pump up her credentials. She could literally pick Miley Cyrus.

I knew we’d circle back to Miley eventually. Speaking of musical artists, I hear you do a mean RZA impersonation.

What!? No. I can’t do impersonations. My friends say I can’t even do a Spanish accent. They say, “Yo, you’ve got this ill block.”

A friend of mine, who used to be an editorial assistant at Riverhead (the publisher of “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao” and “This Is How You Lose Her”), told me you fooled her all the time.

She’s probably confusing me calling up my editor to fuck with him. But that’s great. If I’m getting credit for a brilliant RZA impression just from my crank calls, then I’ll take it.

You came of age as a writer during the golden age of hip-hop, and I’m curious if that had any influence on you.

It’s weird, I have this aching void in the years before hip-hop came into my life because I could never connect to what my friends were listening to. I was a Caribbean kid. The Who didn’t mean shit to me, and neither did the Doors, apologies to everyone. It wasn’t until about ’81 that music began to be a big part of my brain. So oh my God, hell yes, son. I mean I was fucking writing “Drown” when “36 Chambers” dropped.

I’ve always thought Yunior sounded a little like a storytelling MC.

As a writer, I’ve had an enormous range of privileges, from the privilege of being able to emigrate to the privilege of having a family who in the D.R. was actually able to feed us. But one thing I’ve never had is the privilege of being reviewed by anyone who’s able to talk about how much black American vernacular and music is my American baseline. I grew up in black America, and I didn’t discover white America until I went to college. I’ve always thought Yunior’s voice isn’t possible without hip-hop.

So as a Jersey kid, were you a big Redman fan?

Are you crazy? Huuuuge, man. I even like Mobb Deep’s disses on Redman. They hated him, man. They used to have ill punch lines. No shit. I’m glad I never was in hip-hop. I couldn’t have lasted one battle.

All right, give me three albums.

That’s easy. I would say Immortal Technique's "Revolutionary Vol. 2.” Because we’re talking about the Wu, I gotta say “Enter the 36 Chambers.” And of course, “Long Live the Kane.” I saw Big Daddy Kane in a show last month. Motherfucker looks good. And he never broke his line. Never broke his line, son. Never lost his breath. I couldn’t keep up.

Shares