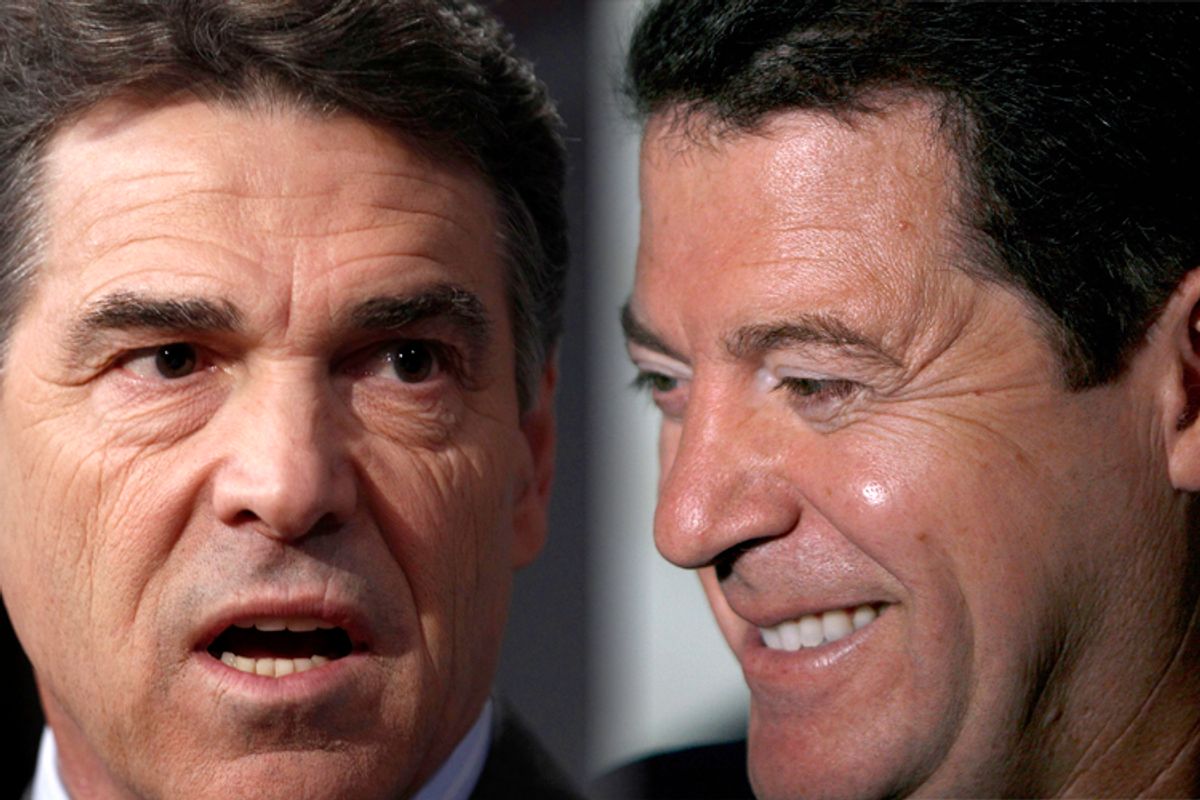

As terrible as the last few years have been for reproductive rights in the United States, growing extremism among antiabortion politicians has resulted in unprecedented awareness of these issues and a groundswell of public support for abortion rights. Wendy Davis' marathon filibuster, bolstered by her Democratic colleagues and the thousands of Texans who showed up at the Capitol day after day, turned the state's sweeping new abortion law and Gov. Rick Perry into national symbols for the right's fixation on policing women's bodies. The same could be said of Mississippi, Arkansas, North Dakota and elsewhere in the country. As a result of these battles, we now know the names, faces and strategies behind the American antiabortion movement, and that knowledge is a powerful thing.

But there is another threat to women's access to abortion happening right now, and it is largely missing from how we talk about the war on reproductive rights: The number of doctors who perform abortions in this country has been steadily declining for decades, and medical schools aren't training enough students to replace them.

"There are a lot of reasons why reproductive healthcare is not well covered in medical school curricula," Lois Backus, executive director of Medical Students for Choice, tells Salon. "But among the most serious causes is the fact that reproductive health topics are still a source of controversy. Even though abortion is the second most common procedure experienced by women of childbearing age, it is routinely ignored in medical education."

According to data from the National Abortion Federation, nearly 70 percent of medical students in the United States have received less than 30 minutes of class training about abortion by the time they finish medical school. This disregard for reproductive health education is an experience Dr. Nancy Stanwood, associate professor and section chief of Family Planning at the Yale School of Medicine and board chair of Physicians for Reproductive Health, remembers well. "We spent literally an hour and a half learning about birth control in two years of lectures," she says. "We spent more time on cochlear implants -- an important, but far less common, procedure."

The problem with this kind of uneven training is that a lack of early exposure to reproductive health issues not only hurts a student's ability to become, as Stanwood notes, "informed physician citizens," it also shapes their career choices. It's far less likely for students to choose a specialization in reproductive health care if it's not something they're hearing about during their training.

Social stigma around abortion may drive the marginalization of this training in medical school curricula, but the scarcity of students being trained to perform the procedure is also directly connected to the proliferation of GOP-backed state-level restrictions -- on funding, on clinics and on physicians themselves.

New regulations mandated under Texas' omnibus antiabortion law threaten to shutter all but five of the remaining abortion service providers in the second most populous state in the country. Mississippi is still engaged in a legal battle to keep its last remaining abortion clinic open; the same goes for North Dakota. Nationwide, close to 90 percent of American counties lack an abortion provider, leaving millions of women without meaningful access to reproductive healthcare.

But for a medical student, the absence of providers can also mean the absence of teachers.

In Ohio earlier this year, the University of Toledo Medical Center, bowing to pressure from state Republicans and Ohio Right to Life, refused to renew its transfer agreement with two area clinics, the Center for Choice and Capital Care Network. Both clinics closed only months later, leaving women like Carolyn Payne, a medical student at the University of Toledo, and 15 of her colleagues, without anyone to teach them how to perform abortions. As Payne told the Chronicle of Higher Education, she now has to travel an hour outside the city to learn this basic medical procedure.

In Kansas, after a measure attempting to ban public hospitals from providing any and all abortion training failed, the Republican-controlled Legislature passed a slightly modified, though similarly restrictive, version of the bill requiring public hospitals to use private dollars to fund medical residents' abortion training. Gov. Sam Brownback signed it, along with dozens of other sweeping abortion restrictions, in April. These kinds of barriers leave training available in the most limited of terms, but make it far from accessible.

It's a national trend with long-term consequences. After all, what does the right to an abortion mean if there are increasingly fewer doctors left to perform the procedure?

But, faced with growing barriers to comprehensive training, medical students across the country have started to fight back. "Students are hungry for this training," Stanwood says. "We're witnessing a really important generational shift. More and more medical students want to be equipped to meet these needs, and reform is beginning to happen because students are demanding it. Change is coming from the bottom up rather than the top down."

Progress has been particularly strong at the residency level. Training opportunities have proliferated in obstetrics-gynecology residency programs and family practice residency programs in large part because of funding from organizations like the Kenneth J. Ryan Residency Program, the continued advocacy of groups Medical Students for Choice and medical students themselves.

But there is still a long way to go. And the stakes couldn't be higher. "This is a very long-term fight that we're in," Backus says. "The medical world is very conservative and resistant to change." She estimates that with the proliferation of antiabortion legislation, this could be as much as a 50-year fight. "But," she adds, "we plan to stay in there."

Shares