It is "one of the oldest and most sticky humanistic dilemmas," wrote George Kennan in 1940, referring to the choice between "a limited cooperation with evil in order to alleviate ultimately its consequences" and "an uncompromising, heroic but suicidal fight against it." Kennan, quoted in Bo Lidegaard's "Countrymen" (translated from the Danish by Robert Maas) was in Prague, contemplating the Czechs' response to the Munich agreement, but "his observation," writes Lidegaard, "is equally true for Denmark during the German occupation."

We all know that 6 million European Jews died in the Nazis' campaign of genocide during World War II, but the degree of slaughter was not consistent across borders. Ninety percent of the Jewish population in Germany, Austria, Poland and the Baltics was murdered. In Yugoslavia and Ukraine, it was closer to 60 percent, and in France it was 26 percent. In Denmark, a nation occupied by Germany from the spring of 1940, less than 1 percent of the nation's Jews were killed by the Nazis. (There's also a legend that the King of Denmark wore the yellow Star of David himself to protest the label the Nazis forced on Jews, but Denmark's Jews were never compelled to wear it.)

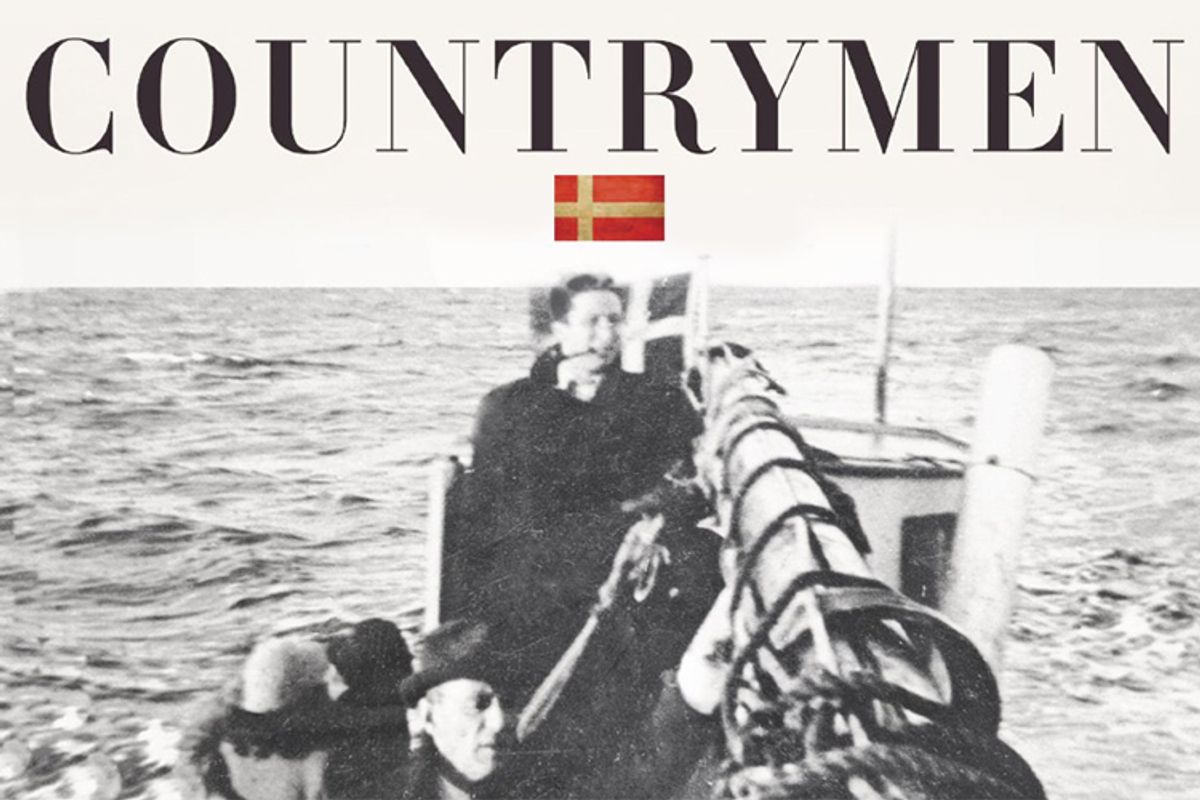

"Countrymen" is the story of how Denmark's Jews survived, and one of the more inspiring narratives of the war. Despite occasional rough spots and repetitions, Lidegaard, a diplomat turned newspaper editor, delivers a skillful braiding of two threads. The first is an account of intricate realpolitik among Danish officials, German administrators and the fanatical regime back in Berlin. The second centers on the diaries -- published for the first time -- of several members of an extended family forced to flee Denmark for Sweden in the autumn of 1943. Lidegaard fleshes out this closer-to-the-ground tale with other first-person stories by and about the many Danish citizens who helped their Jewish countrymen to safety.

It's a canny literary strategy, because while "Countrymen" is in significant part a defense of Erik Scavenius -- Denmark's foreign minister during the German occupation and the nation's chief liaison with the Nazis -- what Scavenius did, while controversial, is not especially thrilling to read about. In counterpoint we have the Danish pediatrician, Adolph Meyer, his two married daughters and their families as they endure the stages of an all-too-familiar catastrophe: The false sense of security in their status as bourgeois, assimilated Jews; the growing sense of uneasiness; the alarming newspaper stories; the friends arriving on bicycles with terrifying rumors; bags hurriedly packed; children and older relatives frantically loaded onto dubious transport; nights spent in deserted buildings or the woods; the boats that never materialize until one suddenly does; little groups huddling silent and out of sight of German police inspectors; and, in the case of Meyer's family, a harrowing passage to Sweden on a fishing boat beset by storms through a channel roamed by German patrols.

Then back to the big picture: "What ultimately stopped the extermination of Jews on Danish soil was the expressed and entrenched Danish opposition to the project," Lidegaard declares. True, the Germans didn't seriously attempt to confront Denmark's "Jewish problem" until relatively late in the war, at a time when many saw the writing on the wall and were maneuvering for survival in a post-Nazi world. But, Lidegaard argues, Germany delayed its action against Denmark's Jews until Oct. 1, 1943, precisely because Scavenius and others had persuaded them that any such attack would so outrage the Danish populace as to jeopardize the "policy of cooperation" that had made the occupation relatively peaceful. In fact, it was only after a series of strikes, protests and other forms of unrest provided the occupiers with an excuse to declare martial law that the Germans saw their chance.

And even then, many were ambivalent. Hitler viewed Denmark as a valuable political example that demonstrated the benefits of capitulating to German might. In 1940, Danish leaders reluctantly conceded to the occupation, believing that their border with Germany was impossible to defend. Not every Dane agreed with this decision, but most preferred it to "Norwegian conditions," in which an active, armed resistance was met with brutal reprisals (as happened in Norway). The Nazi war effort also came to depend in some part on Denmark's agricultural produce. As a result, Germany's leadership had its own vested interest in maintaining the "policy of cooperation." Danish officials strove to maximize the advantage of this interest in a series of moves and countermoves leading up to and following the arrest and deportation of 450 Danish Jews in 1943. Through their efforts and vigilance, most of these deported citizens survived the war and returned to Denmark.

Lidegaard attributes this miracle to "politics" -- not just the politics of international and wartime diplomacy but the ideology of nationalism. Specifically, it was the ability of Denmark's Social Democratic leaders "to link 'the Danish' with 'the democratic' -- using the two synonymously. Hence, to be a good, patriotic Dane was tantamount to resisting totalitarian ideas and defending representative government, democracy and humanism." This is the sort of wholesome, right-thinking mentality that often leads outsiders to call Scandinavians boring, but in 1943 it achieved a transcendent beauty, as ordinary Danes in great numbers responded to the German action against their fellow citizens with indignation and reflexive efforts to help. Lidegaard offers countless examples of farmers, white-collar workers, laborers -- people from every walk of life, including the Danish police -- opening their homes, offering rides, misdirecting German soldiers, carrying messages, protecting personal property, concealing fugitives in hospitals and so on, to help the Danish Jews escape to Sweden, where they were welcomed without reserve.

As Hannah Arendt wrote in "Eichmann in Jerusalem," Denmark "is the only case we know of in which the Nazis met with open, native resistance, and the result seemed to be that those exposed to it changed their minds." Even the Germans charged with executing the order to arrest Denmark's Jews pursued it halfheartedly, because, both Arendt and Lidegaard believe, they were confronted by a unified people who, though "defenseless and occupied" refused to accept or participate in their twisted version of reality. "They had met resistance based on principle," Arendt explained, "and their 'toughness' melted like butter." While Lidegaard cautions against assuming that the same formula might have worked for other European nations, he does see the story of Denmark's Jews as proof that "hatred of the different is not some primordial force," waiting to be unleashed in every group. Instead, it's a "political tool" that the unscrupulous are all too willing to use for their own advantage. But only if we let them.

Shares