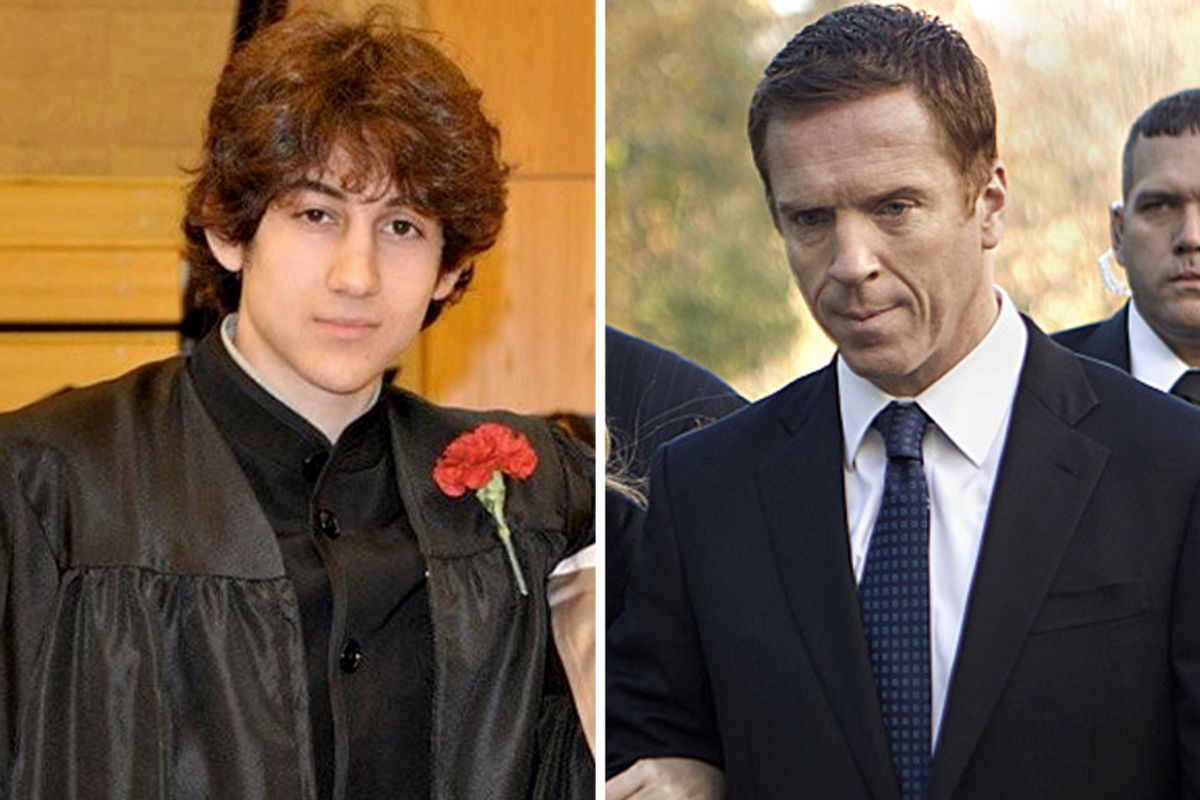

The most sustained -- if sometimes hyperbolic -- depiction of terror in recent years has been on a show where the terrorist sits on many borderlines. He's both a radicalized Muslim and a member of what's constantly framed as the standard white American family; he aspires both toward a better life for his family and for revenge against the United States. Nicholas Brody, of "Homeland," which returns Sept. 29 on Showtime, is an entirely new sort of potential terrorist on-screen -- one who's humanized, and one who exists outside the sort of enemy-state narratives American viewers had grown so comfortable with. And "Homeland" is hardly niche: The show and Damian Lewis as Brody won the best drama series and best drama actor trophies at last year's Emmys and are nominated again at Sunday's ceremony.

In past decades, Hollywood villains have often represented entire nations or peoples -- the Soviets in the original "Red Dawn," say, or the pan-Euro baddie in "Die Hard," or the Islamic terrorists in "The Siege." Such villains didn't necessarily convey that entire peoples were the enemies of the U.S.; they did, however, make clear that filmmakers had a certain overarching conception of what "the enemy" would look like. In recent big-budget films where the destruction is far more vast than past filmmakers could've imagined, though, the enemies are not humans but aliens. The death toll in recent films like "The Avengers" and "Man of Steel" is stratospheric -- but in both cases, the people responsible aren't even people.

"In Batman and Superman, these big-budget films, there's a post-9/11 idea of terrorism, in that they involve innocent people being killed, buildings being destroyed, and the bad guys are supervillains," said Boston Globe film critic Ty Burr. "This is how we express our anxieties. We pour it into the blockbuster, superhero container." In order to cope with the fact that enemies of the state actually exist and have made generation-defining contact, Hollywood has reframed threats to U.S. life and limb as extraterrestrial or otherwise inhuman (like "The Dark Knight's" almost supernatural Joker character). In the recent "Iron Man 3," the villain the Mandarin, who'd been portrayed as Chinese in comic books, was played by Ben Kingsley, a British actor, and ultimately revealed to be a British fellow putting on an act.

Framing villains as being of a particular nationality is the last thing skittish and war-weary Americans want; think of one element of the outcry over "Zero Dark Thirty" last year -- the visceral reaction against on-screen portrayal of U.S. torture practices.

Said film critic A. S. Hamrah, "Because of the moral crisis of the wars in the Bush and Obama eras, people don't know who's good or bad anymore. There was a brief period during which the enemy was aliens. The movie 'Battleship' made aliens the enemy." The same is true of "Pacific Rim," a would-be blockbuster framed around an international crew of heroes saving the world from undersea monsters -- it was practically designed to play all along, well, the Pacific Rim.

And in last year's remake of "Red Dawn," the villains taking over the U.S. were changed at the last minute from Chinese to North Korean. The idea of a North Korean military takeover -- laughable on its face -- wasn't really any more implausible than anything else in the big, broad Chris Hemsworth action film, and the film was salable in the Chinese market.

Why bother to think too hard about an element that would only end up alienating someone, somewhere? "The goal of each action scene is to top the prior action scene," said Lynda Obst, the author of "Sleepless in Hollywood" and the producer of many films, including "The Siege."

"So why would you want a realistic hero or villain? Nothing in the frame of the narrative is realistic."

Presented with the most uncertain world in generations, filmmakers have provided the safe scenario of our enemies coming from other galaxies -- and ultimately being vanquished. We purge our fears by representing them in ways that are literally impossible. Burr cited several small-budget films or foreign films, like "The East" and "Day Night Day Night," that have approached the question of the motivations of a terrorist from different angles. But "Homeland," a more widely seen and discussed work, has aired on TV -- it gets more time to explore its key questions.

As the film historian David Thomson pointed out, television may not deal often with terrorism as such, but does a better job than film of looking in depth at what makes a person bad or an enemy of society. "We're in a very odd situation now whereby if you look at long-form television, which arguably is the best work we're doing now, it's a series of portraits of families and individuals not just into crime but serious killing. These characters are not excused or forgiven, but neither are they brought to justice." Big-budget film can't draw out these ever-more-real-seeming tensions in American life -- or it chooses not to.

And so "Homeland's" Brody, despite some high-decadent turns the series took in its second season, seems more relevant than ever. As Burr, the Boston critic, said, "It's relevant to how Dzhokhar Tsarnaev is portrayed. There's sympathy because he's from this country and not another. The wires cross and he's an interesting case. [...] Some people look at him and see him strapped to a bomb in a plaza overseas -- and some people look at him and see just a kid who went to school and played sports. I don't think that's ever happened before -- at once a foreign fanatic and a homegrown terrorist for whom we feel a qualified sympathy." It's exactly these sorts of contradictions that have fueled Brody, and that give both "Homeland" and "Jahar" coverage a sickening frisson.

We're in an era during which an American-raised kid brought America its biggest day of terror since the one that spurred a decade and more of safe fantasies of alien attacks. But even representing him on the cover of a generally pop-culture-centric magazine (in the context of a reported news feature) was deeply controversial. It's hard to imagine many moviemakers taking the risks that "Homeland" does -- the risk of looking at an ever-more-confusing world scene and attempting to diagnose it, rather than looking to the stars and dreaming of safety.

Shares