Should criminal punishments be reduced if a perpetrator (of, say, a murder) claims he was simply reacting to being hit on by someone of the same sex? It might sound crazy, but it's a decades-old defense known as “gay panic.”

This legal concept includes defenses rooted in the traditional criminal law principles of “adequate provocation” (basically, something so egregious and recent that it would reasonably inspire rage) or “diminished capacity” (basically, something that at least temporarily would hamper self-control). It’s a contentious concept.

Following the alleged murder of 69-year-old Ever Orozco in Queens, New York City activists and a City Council member are urging an end to the so-called gay panic defense.

“Sometimes even the juries are infected with this idea that gay panic defense is OK,” council member Daniel Dromm told Salon, and “that a heterosexual man in particular needs to protect himself from the advances of a gay male.”

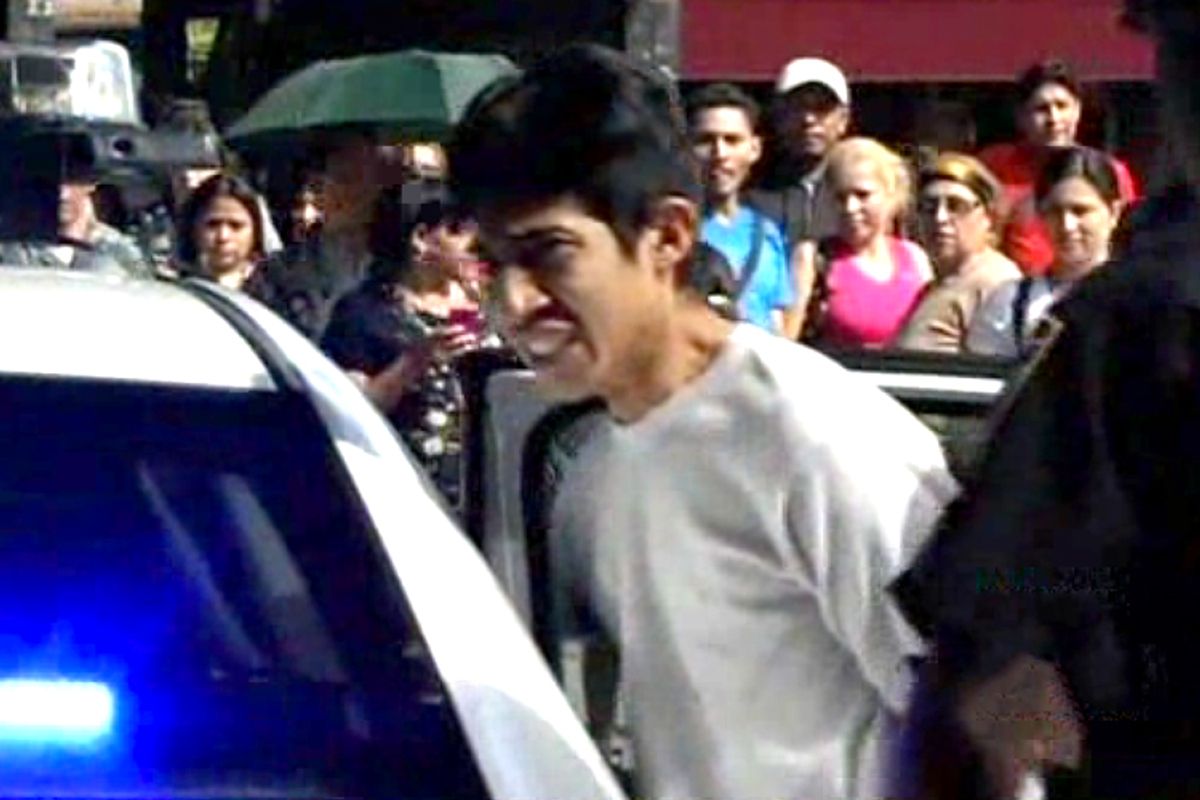

Dromm told Salon that 22-year-old defendant Steven Torres had told police Orozco “blew kisses at him.” Local media also reported that Torres claimed Orozco, and another man he allegedly attacked previously, had blown him kisses. Echoing other accounts of Orozco’s killing, one man told NBC, “There was a lot of screaming, and all I could see was the guy was stabbing him – stabbing him and stabbing him.”

“Even though this man is not gay … homophobia still killed him,” Karina Claudio, an organizer with the community group Make the Road New York, told Salon. Torres was reportedly arrested for second-degree murder and sent for a psychiatric evaluation. Following Orozco’s killing, MRNY held a press conference with Dromm and other allies to condemn the alleged hate crime and denounce any potential “gay panic” defense.

“These kinds of doctrines,” Yale law professor Dan Kahan told Salon, “they are measures of the kinds of attitudes that people have about what people should appropriately value, and who should be appropriately valued in light of how they’re behaving.”

Dromm told Salon that following their press conference, he was told the defense did not intend to advance a “gay panic” defense in Torres’ case. Nonetheless, Dromm said that the persistence of “gay panic” defenses in U.S. courts “absolutely” contributes to the prevalence of deaths like Orozco’s. “Somewhere along the way,” argued Dromm, the killer “had to have learned that it would be OK, that if a gay person made a pass at you … you could do whatever you wanted to them.”

“Gay panic” defenses are now under intensified scrutiny: The American Bar Association voted last month to urge legislators “to curtail the availability and effectiveness” of defenses “which seek to partially or completely excuse crimes such as murder and assault on the grounds that the victim’s sexual orientation or gender identity is to blame for the defendant’s violent reaction.” D'Arcy Kemnitz, who directs the National LGBT Bar Association, told Salon in an email that the resolution's unanimous passage "gives a voice to countless lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender victims of violence, a voice we never hear because they are no longer here to speak for themselves." Dromm said he’s exploring legal options to tackle the issue, including potential City Council resolutions urging a further strengthened ABA stance against “gay panic,” or urging the state Legislature to amend its criminal code to make clear it’s not a legitimate defense.

“Honestly, there’s a bit of obfuscation and confabulation going on,” in discussions of “gay panic,” said Yale’s Kahan. “If you are inclined to recognize a certain kind of emotional valuation of another person’s behavior as being appropriately condemnatory,” he told Salon, “well, then you find the resources in the law to make it receptive to that.”

Kahan noted that such defenses often “sound like they’re talking about psychology”: how, for example, being hit on by another man would affect a man’s capacity for self-control. But Kahan argued that such defenses are inherently premised on social norms – not just the probability of “people blowing up” in a certain situation, but whether “the provoking event was something that put at risk something that a reasonable person ought to value,” like a man’s masculinity, or his wife’s fidelity.

“What they’re talking about is whether they want their law to say that somebody who experiences that kind of outrage in public – you would regard me as if I were a woman – is appropriately valuing his honor,” said Kahan. “Or is that idea, that being regarded that way by another man entitles you to be enraged, something itself that’s ridiculous?”

Kahan noted that the credence accorded to various defenses has shifted over time: Over recent decades, Americans have become more sympathetic to the defense that a woman killed a man because he was abusing her, and less sympathetic to the once-commonplace defense that a man killed another man because he was having sex with his wife. “The stock of the cuckold has kind of been falling,” said Kahan.

As examples of how social norms shape the sense of what’s an acceptable defense, Kahan noted that common law gave greater weight to rage at a man who had sex with your wife than rage at a man who had sex with your mistress, and that a claim like “I kind of blow up when I see little girls on the street” would never receive the credence sometimes given to rage at gay people.

Make the Road’s Claudio told Salon that in the wake of Orozco’s killing, “we want to see a change in attitudes and a change in policy,” including workplace protections and public school curricula addressing LGBT discrimination. She noted that unlike some politicians who shared her opposition to “gay panic,” she did not support addressing anti-gay violence by increasing police presence. Rather, Claudio said that in the Queens neighborhoods where she’s organizing, “the cops themselves are the ones checking people’s genitals when they’re stopped and frisked or confiscating people’s condoms and accusing them of prostitution.”

Kahan described the spread of hate crimes laws that can increase punishments for assaulting people perceived to be gay, and the increased scrutiny on gay panic defenses that can mitigate punishments, as two signs of shifting norms: “People are battling to define what’s the appropriate way to manifest your maleness. And the idea that you shouldn’t be outraged by somebody treating you as if you were gay, that’s one of the focal points of that.”

“People are being told that our sexuality is evil,” council member Dromm told Salon. He said that while he hadn’t himself been assaulted for being gay, “you always walk down the street with one eye over the shoulder.”

“The true path to gay equality,” said Dromm, “means that, you know, we’re going to be integrated into the overall society.” He added that he “would never go into a heterosexual bar and make a pass at a guy … I’ve been conditioned already that that’s just, you know, unacceptable. But really, true liberation would mean that I could do that, or should be able to do that. So somewhere, I’ve gotten the message that, you know, be careful.”

Shares