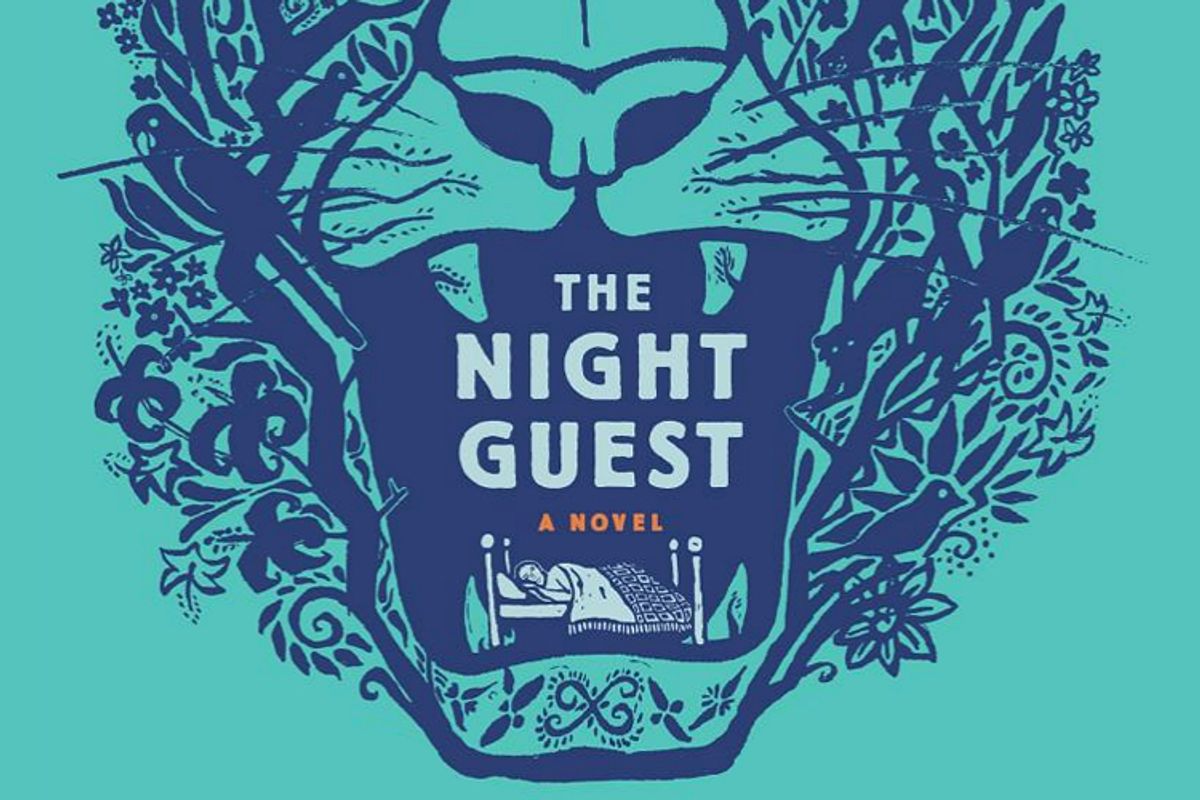

Fiona McFarlane's first novel, "The Night Guest," is a little bit ghost story, a little bit crime fiction and a whole lot unsettling. It begins with the main character, Ruth -- a widow in her 70s, living alone -- convinced that she hears a tiger moving stealthily through her house at night. Her grown son doesn't appreciate being rung up in the wee hours of the morning with this news, and figures the dream is a holdover from his mother's childhood as the daughter of missionaries in Fiji. Fortunately for everyone, a strapping young woman named Frida materializes at Ruth's door the next day, announcing "the government sent me" and commencing to scrub the floors, cook the meals and do the shopping. To Ruth's gratification, Frida doesn't dismiss her tiger theory out of hand.

So begins an extraordinary and sometimes disturbing relationship. "The Night Guest" is a novel of uncanny emotional penetration; it had me flipping to the back cover more than once to scrutinize the author photo. How could anyone so young portray so persuasively what it feels like to look back on a lot more life that you can see in front of you? However, Ruth isn't entirely out of the game, despite having been stranded in a seaside house on the outskirts of a small Australian town by a husband who keeled over while taking his morning constitutional. Much of the novel concerns her endearingly quizzical memories of her youth in Fiji and of Richard, a slightly older doctor she met there and with whom she fell in love. Richard turned out to be already engaged, but now he, too, has been widowed, and in a moment of bravado, Ruth, who hasn't seen him in 50 years, invites her old flame for a visit. (Ruth's son, to her annoyance, wants her to invite "a sensible woman he's known forever who'll ring him up and tell him everything.")

Frida becomes Ruth's great conspirator in this tryst, playing as deft and tactful a retainer as Bruce Wayne's Alfred. Ruth and Richard's reunion results in one of the more remarkable sex scenes I've ever read, a depiction of what physical intimacy must be like after lust has mostly burned off and left the field to an infinite tenderness. Yet Frida is really the person with whom Ruth forms the most intense bond. The older woman marvels over her caregiver's fantastical and ever-changing hairstyles, her "maritime stride" and "Valkyric majesty" -- her overwhelming and occasionally intimidating vitality and competence and fearlessness: "Frida was the one who wanted," Ruth muses. (She does a lot of musing.) "She wanted clean floors, a smaller waist and differently colored hair. Frida filled the world with her desires. And Ruth admired it. Why not be like that?" Plus Frida is willing to tackle the tiger, even if she does retain a certain skepticism. "What would a tiger want with you?" she asks the first time Ruth tells her about it.

Frida, however, turns out not to be quite what she seems. Then again, Ruth isn't really herself either. Their relationship is funny, antagonistic, affectionate, mutually dependent, but ultimately unstable. A low thrum of terror builds ever so gradually as "The Night Guest" proceeds, and its source is the slippery connection between the mind and the world. Is there a tiger, or not? Is Frida a friend or a foe? (Or a Fijian, as Ruth intermittently insists, without any evidence for that belief.) When you can't always trust your own perceptions or orientation, how is it possible to judge whether or not you've been betrayed?

What makes "The Night Guest" especially unnerving is the way it immerses the reader in a mind that is slowly slipping its moorings. As McFarlane depicts it, in clean, sinuous prose, you begin to lose your self by burrowing deeper inside it; Ruth wanders the byways of her own psyche, preoccupied with the past and with the ripples sent through her imagination by the most mundane triggers. Waking up to a somehow "disheveled" living room the morning after one of the tiger's visitations, she thinks "each piece of furniture seemed unmoored in the flat, insipid light, as if it had been stranded in its insistence on the ordinary. Ruth had the feeling that her whole house was lying to her."

It's a premise that sounds "small," but one that blossoms from within. Ruth's associations have a wide-ranging acuteness that belies their dotty surface. When a sulking Frida leaves her stranded in the yard with a spasming back, Ruth feels "the way she did on plane rides: empty, suspended and consumed by the inconvenience of urination." You're in her head, and that head gets less and less sound as the novel progresses, but it's a strangely delightful place to be, for all the darkness surrounding it.

Shares