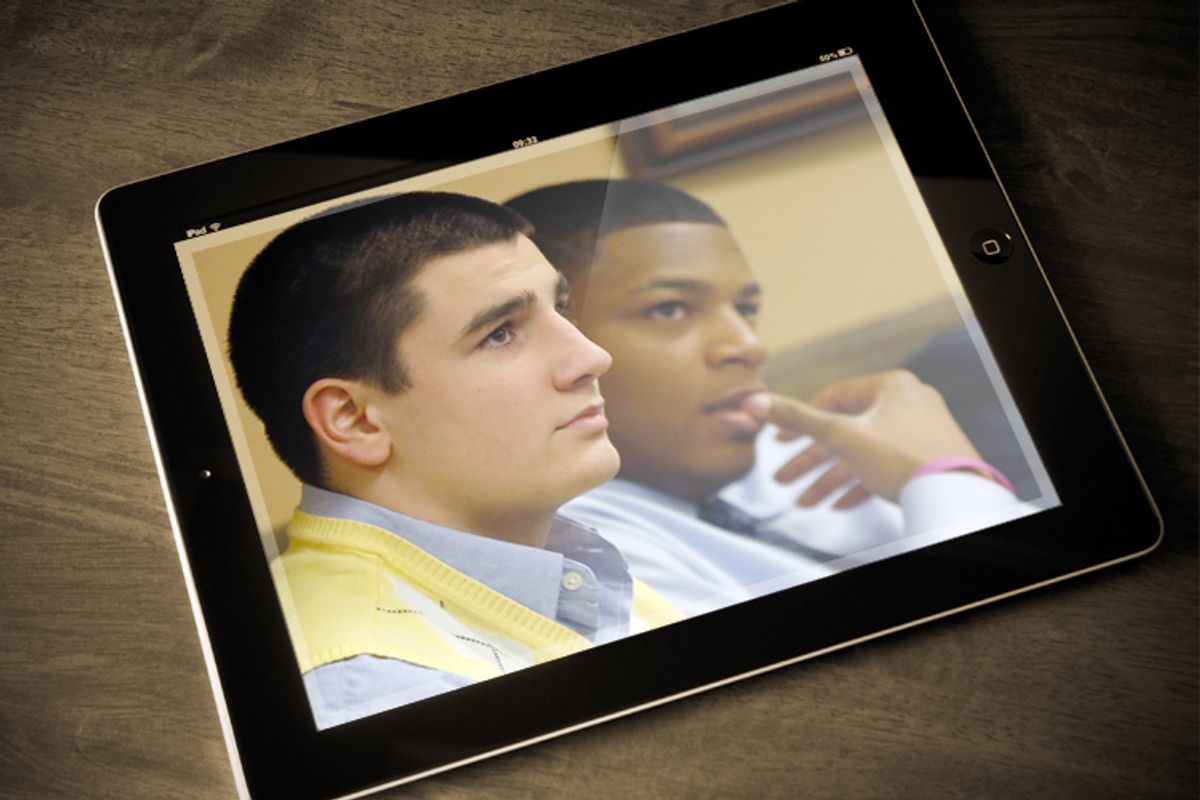

This week, the terrible news comes from Maryville, Mo. In a well-reported story for the Kansas City Star, Dugan Arnett details a situation as appalling as it is familiar. The comparisons to what took place in Steubenville are inevitable. Young men and women, popular athletes and the girls who want to enter their orbit, alcohol, allegations of rape, video evidence, a town that has, for the most part, rallied around the young men and blamed the victims, and charges eventually dropped.

Or the terrible news comes from Athens, Ohio, where onlookers took pictures and video, and gleefully turned to social networks to comment on an alleged sexual assault taking place on a public street.

Or the terrible news comes from Annapolis, Md., the U.S. Naval Academy, and two Naval football players facing a court-martial for sexually assaulting a young woman at a party. She learned the extent of what happened to her via social media.

There is a strange intersection lately between young men and women, the consumption of alcohol, sexual assault and social media — downward spirals where the horror only compounds as new details are revealed. Whenever such cases come to light, vigorous discussion is inevitable and probably necessary. We have to talk about these cases, right? We have to point out each new sign that rape culture thrives in our country. We have to try to come up with solutions that keep people safe.

As I’ve considered what happened in Maryville, or Steubenville, what happens all over this country, day after day and year after year, I wonder about the line between having necessary conversations about sexual violence and losing sight of what prompted these conversations. Are we fighting for these victims? Are we fighting for ourselves? Or are we just fighting?

We have to talk about young women exercising better judgment to reduce their risk because it’s such a seductive fantasy: If we’re good enough girls, maybe we won’t get raped. Slate’s Emily Yoffe offers the latest iteration of this fantasy in a piece that purports to advocate common sense. Young women should avoid binge drinking; they should avoid making themselves unnecessarily vulnerable. Yoffe essentially suggests that an excess of alcohol in a woman’s bloodstream turns otherwise normal men into rapists, so we best avoid that. Yoffe also works through her own anxieties as a parent. She has a daughter heading off to college next year, you see. And of course, there is this incontrovertible evidence: “I have never been so drunk that I browned out, blacked out, passed out, or puked from alcohol ingestion.” If she can maintain her self-control, so should we all.

It’s natural to dismiss Yoffe’s piece and others of its ilk as click bait, but these pieces continue to get published because they satisfy the cultural narrative that victims are ultimately responsible for their own violation. It’s well and good to suggest that predators should avoid predation, that rapists should just stop raping, but no one wants to hear this brand of genuine common sense that places the culpability for sexual violence where it actually belongs. We don’t dare imagine such a perfect world.

Instead, we surrender to our cynicism. We continue to remind young women that they should make better decisions, drink less, wear modest clothing, remain chaste, avoid walking alone at night, as if there is some ideal combination of respectable behaviors that will definitively protect women from sexual violence. Why don’t we just tell women to avoid going to college while we’re at it? The most absurd part of Yoffe’s piece is the suggestion that we’re “reluctant” to tell young women to stop getting drunk, as if tactics for rape avoidance have not been a constant refrain for young women throughout their lives.

As with many contentious issues, there seems to be little room for nuance when talking about sexual violence. It’s not that Yoffe is wrong, but she isn’t right, and it’s hard to express that because sexual violence is so fraught and intimate an issue for so many people. Some will no doubt dismiss the many and inevitable responses to Yoffe. Already, writers at Jezebel, the Atlantic Wire, Huffington Post and the Frisky have weighed in. These pieces have offered more effective ways of talking to young women about risk, accused Yoffe of victim blaming, and pointed out the myriad of ways Yoffe is wrong. They’ve repeatedly suggested that maybe we talk to young men about not binge drinking and not taking advantage of drunken young women. No matter where we stand, we all ardently believe we’re making the most sense. This cycle of click bait and response is frustrating because we cannot seem to break it. This cycle forces everyone into positions where they have to take an all-or-nothing stance, simply to be heard. But what's the alternative? To say nothing? To ignore the click bait that perpetuates a toxic culture of sexual violence?

Writers like Emily Yoffe want to be realistic. They believe they see the world as it is — unchangeable and rather grim. Men aren’t going to stop raping so we must protect ourselves as best we can. Those of us who disagree with this stance, we also believe we see the world as it is. We’re fighting so hard for that world to change, to become at least a somewhat more perfect world, because it’s so hard to accept a reality where women won’t ever have the same freedoms as men.

Shares