He threw off his provincial upbringing to study acting in New York City, and went on the road with a professional touring company. In the years after World War I, he married a divorced "countess" and bummed around Europe, running a traveling exhibition about Lawrence of Arabia, living on an island in Budapest and doing that classic Lost Generation thing: writing a novel about how stultifying things were back home. When that marriage broke up, he returned to the States where, in time, he entered into an affair with a brilliant Jewish woman -- married, but with a husband willing to look the other way, a man he eventually befriended. He always believed he had fathered her daughter.

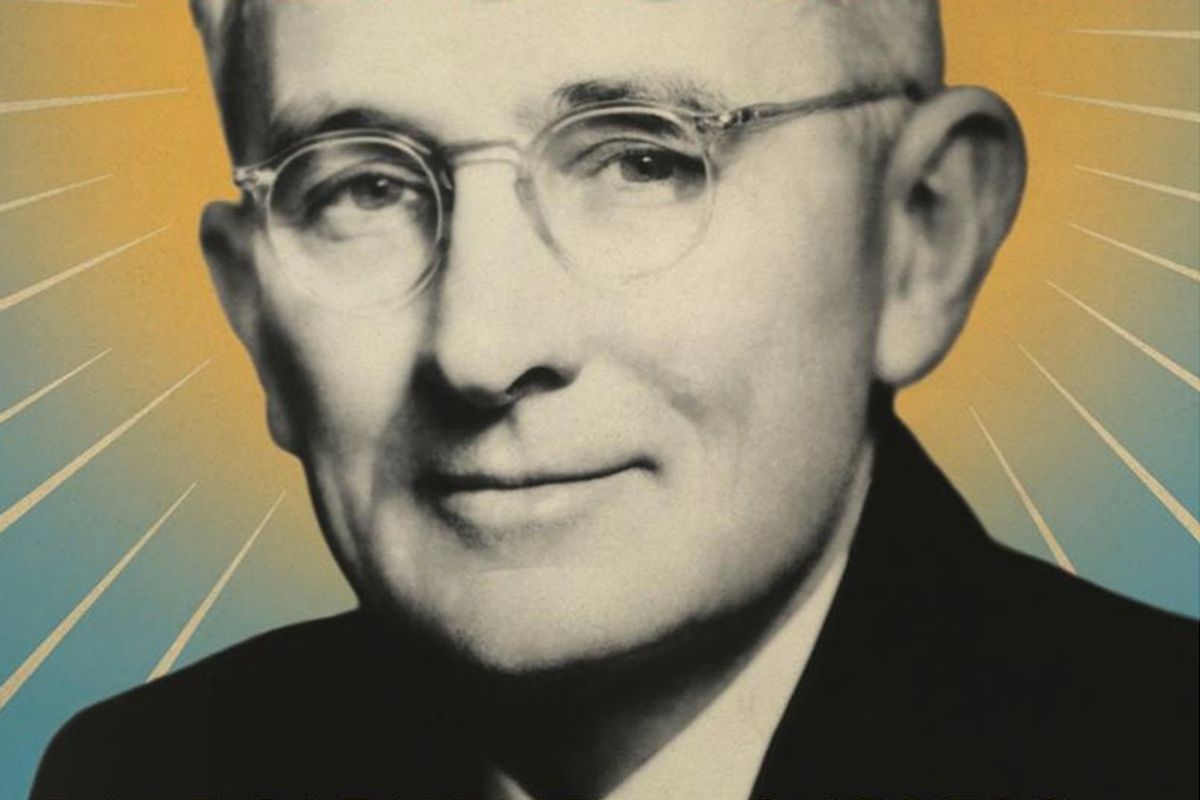

This bohemian-sounding résumé belongs to a man who, in many eyes, personifies the blandest, most anodyne face of American culture: Dale Carnegie, author of "How to Win Friends and Influence People," one of the best-selling and most influential books of the 20th century, and the father of the modern self-help movement. Born into a struggling Missouri farm family, Carnegie became the head of a thriving company that mounted courses in public speaking across the nation. Contemporary figures as diverse as Lyndon B. Johnson and Jerry Rubin, the founder of the Yippies, as well as such business-world icons as Warren Buffett and Lee Iacocca, credited Dale Carnegie Training courses with launching their careers.

Also Charles Manson, according to Jeff Guinn's biography of the mass-murder mastermind published earlier this year. The notorious sociopath took classes based on "How to Win Friends and Influence People" while serving time in a federal penitentiary for grand theft auto. Manson's particular area of expertise was a key Carnegie precept: Get people to do what you want by convincing them it's their own idea. That was how he persuaded his followers to do what they didn't even realize was his bidding.

Carnegie -- who, to judge from Steven Watts' new biography, "Self-Help Messiah: Dale Carnegie and Success in Modern America," was a perfectly lovely man -- would no doubt have been horrified to learn of this fact, but I confess that it is precisely this revelation that prompted me to pick up Watts' book (and download a copy of "How to Win Friends and Influence People"). What sort of program lends itself equally well to would-be Rotary Club presidents and leaders of homicidal doomsday cults? What sort of man could have devised it?

Given the centrality of Carnegie's place in American culture -- he both embodied and professed the self-made, rags-to-riches story at the core of our identity -- it's surprising that this is the first independent biography of the man. While Carnegie wasn't conflicted or complex enough to make for a fascinating character, a Library of Congress survey did name "How to Win Friends and Influence People" the seventh most influential book in American history, and American Heritage magazine included it among the 10 books that have most shaped the American character. To this day, you can find thriving Carnegie-branded courses across the globe.

Watts -- a professor of history at the University of Missouri-Columbia and author of similar books on Hugh Hefner, Henry Ford and Walt Disney -- wisely opts to link Carnegie's life story to the "massive reorientation of American life in the early decades of the 20th century." Industrialization and urbanization transformed the nation from a society with a rural, traditional ethos of "stern morality and studied self-control" to one of "consumer abundance, leisure and entertainment" in which individuals pursued both worldly success and the nirvana of self-fulfillment.

Granted, Watts is not the most scintillating writer himself, and he annoyingly insists on referring to the pious, agrarian Protestant values of Carnegie's background as "Victorian" (anyone who thinks the Victorians were stoic and self-restraining has never seen the Albert Memorial), but once you realize that he's talking about the residual ethos of America's Puritan origins, you can ignore that. He's better at teasing out the ways Carnegie played Virgil to a generation of lower-middle- and working-class people determined to collect on America's promise of social mobility. Hard work and clean living were indeed what the Victorian-era elites -- and, in fact, all elites throughout history -- dictated to such underlings, but Carnegie showed them the real way to navigate the corporations, government agencies and other large bureaucratic organizations where the real opportunities for material advancement awaited. As he stated again and again, the essential skill in this new world is an ability to work well with other people.

Carnegie's directives were not sophisticated, or at least they no longer seem so today, when they reappear over and over again in each new self-help craze, from "The Secret" to "In Search of Excellence." Think positive, guide with praise rather than criticism, make the other person feel important, be yourself, and so on. While Carnegie could sound cynical -- "Remember that a man's name is to him the sweetest and most important sound in any language" -- he was also good-natured enough himself not to anticipate that the techniques he advocated could be adapted to destructive ends. Charles Manson would have been unfathomable to him -- his great criticism of Hitler was that the man clearly never listened to anyone but himself, and there's a certain sneaky wisdom in that -- so he was relatively untroubled by the darker side of his program, the aspects that caused critics to label it insincere and manipulative.

As a character, Carnegie is likable; he treated his staff well, entered into genuine and respectful partnerships with women and was devoted to their children, including the girl who knew him as "Uncle Dale" and always wondered why he insisted on being so involved with her life. He was considerate and generous to friends and strangers, even when the demands of being the America's foremost authority on getting along with people began to wear on him. He had just enough originality to try kicking off the traces of Middle America and just enough common sense to realize that Middle America was where he belonged.

Yet Carnegie, like America itself, remained almost willfully innocent, and he often had difficulty defending his program from those who pointed out how it contradicted itself or could be misused, the way, for example, that fixating on self-fulfillment might lead to a society of solipsistic narcissists. Carnegie died, of Alzheimer's Disease, in 1955 -- before the Vietnam War, the counterculture, the Me Generation and the dissemination of psychotherapy into every nook and crevice of American society. (Watts, who sees Oprah Winfrey as Carnegie's rightful heir, feels he played a major role in the rise of the latter two.) And before Charles Manson earned his bloody claim to fame. Sometimes, it turns out, thinking positive just isn't good enough.

Shares