In the spring of 2005, Georgia-Pacific Corp. found itself facing nearly $1 billion in liability from a product it hadn’t made in nearly three decades: a putty-like building material, known as joint compound, containing the cancer-causing mineral asbestos.

In the spring of 2005, Georgia-Pacific Corp. found itself facing nearly $1 billion in liability from a product it hadn’t made in nearly three decades: a putty-like building material, known as joint compound, containing the cancer-causing mineral asbestos.

Named in more than 60,000 legal claims, Atlanta-based Georgia-Pacificsought salvation in a secret research program it launched in hopes of exonerating its product as a carcinogen, court records obtained by the Center for Public Integrity show. It hired consultants known for their defense work to conduct studies and publish the results, with input from the company’s legal department — and is attempting to keep key information hidden from plaintiffs.

The Consumer Product Safety Commission had banned all asbestos-containing joint compound as of 1978, and Georgia-Pacific, maker of a widely used version called Ready-Mix, had raised no objection. But in 2005, as asbestos-related diseases with long latency periods mounted, the company revisited the issue with one aim: to defend lawsuits filed by people like Daniel Stupino, a part-time renovation worker who died last year of mesothelioma, a form of cancer virtually always caused by asbestos exposure.

Under its research program, Georgia-Pacific paid 18 scientists a collective $6 million, documents show. These experts were directed by Georgia-Pacific’s longtime head of toxicology, who was “specially employed” by the company’s in-house counsel to work on asbestos litigation and was under orders to hold “in the strictest confidence” all information generated.

This framework, taking a page from the tobacco industry playbook hatched years earlier, allowed Georgia-Pacific to control the science and claim all communications as privileged — not subject to discovery in litigation. A New York appeals court held recently that the communications “could have been in furtherance of a fraud,” an allegation the company has denied.

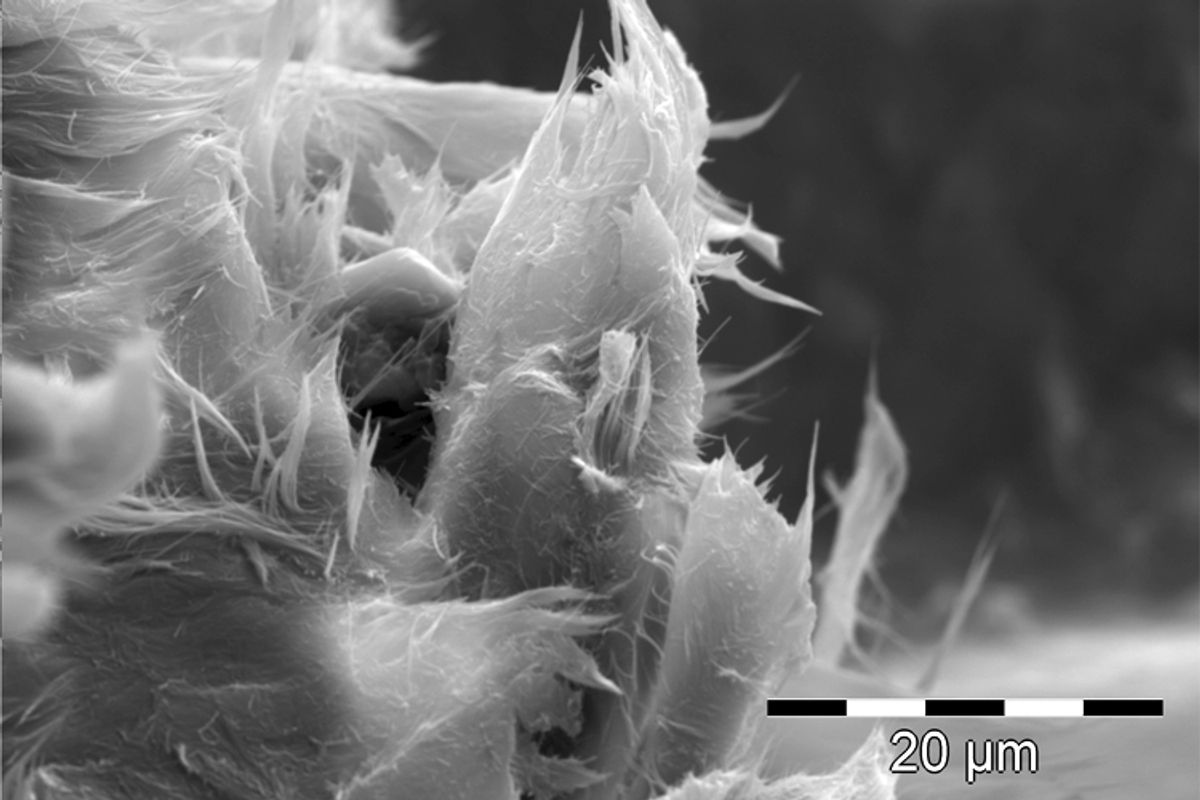

Some of the researchers hired by Georgia-Pacific sought to re-create versions of Ready-Mix and a dry joint compound that contained asbestos in the 1970s. Others tried to estimate historical worker exposures to dust from sanded compound. Still others exposed laboratory rats to the reformulated materials, employing suspect protocols; they reported that asbestos fibers were cleared quickly from the rodents’ lungs and posed no cancer threat, a theory many experts reject.

Thirteen company-funded articles were published in scientific journals. A Georgia-Pacific lawyer offered pre-publication comments, casting doubt on the objectivity of the science.

The Atlanta-based company’s research program fits into a broader pattern chronicled this year in the Center for Public Integrity series Toxic Clout: Industry’s use of well-paid experts to minimize the hazards of toxic chemicals and fend off liability, regulation, or both.

A spokesman for Georgia-Pacific, Greg Guest, declined to answer questions about the project, referring a reporter to court pleadings. In one document, the company says it “properly commissioned studies to explore scientific issues that repeatedly arise in joint compound litigation, disclosed its role in the studies themselves, and submitted them to the technical rigors of scientific peer review by qualified scientists who were neither affiliated with nor selected by Georgia-Pacific.”

Now owned by Koch Industries Inc., Georgia-Pacific has refused to turn over certain study-related documents to plaintiffs in thousands of asbestos cases from the five boroughs of New York City, which have been consolidated in a Manhattan court. The company contends the materials are protected under attorney-client privilege and as attorney work product. These protections can be forfeited, however, amid evidence that a client engaged in a “fraudulent scheme.”

In a unanimous decision in June, a New York appeals court found reason to believe Georgia-Pacific had perpetrated such a scheme and ordered the company to hand over the documents to a judge for in camera inspection. Guest said Georgia-Pacific had not decided whether to appeal.

“There’s something extremely smelly about claiming attorney-client privilege for something that is being claimed at the same time as good science,” said Sheila Jasanoff, a professor at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government who has written extensively about litigation-driven research. “Legal confidentiality protections should not be placed around good science.”

The company is trying to “rewrite history,” said Linda Reinstein, co-founder of the Asbestos Disease Awareness Organization, a victims’ advocacy group. “Georgia-Pacific funded junk science in an attempt to contest the known facts about asbestos and negate its culpability in this man-made disaster,” said Reinstein, whose husband, Alan, died of mesothelioma.

Decades later, a deadly killer

The dangers of asbestos were first noted more than a century ago by British factory inspectors. In the 1920s, writes Barry Castleman, an asbestos historian and environmental consultant, “The lung-scarring disease asbestosis was named and described in detail in reports of totally disabling and fatal cases.” Reports of lung cancer among asbestos workers surfaced in the 1930s and mesotheliomas — incurable malignancies usually found in the membrane surrounding the lungs — began to appear in the 1940s.

It was around this time that drywall — and, by extension, joint compound — became exceedingly popular among builders trying to meet the demands of the post-war boom in America. “Low cost housing went into mass production in 1947-1948,” researchers with New York’s Mt. Sinai School of Medicine wrote in a 1979 article. “Wallboard sections were soon manufactured to fit standard room dimensions, enabling a worker to construct living quarters within a few hours. Drywall construction was also considered superior [to lathing and plastering] because of its adaptation to soundproofing and fire codes.”

Manufacturers began adding fire- and heat-resistant asbestos to joint compound as a reinforcing agent. The practice continued well into the 1970s, even as evidence of the mineral’s carcinogenicity mounted.

Georgia-Pacific got into the joint compound business relatively late, acquiring Bestwall Gypsum Co. in 1965. It sold Ready-Mix, a paste that could be applied directly to walls, as well as a dry mix, to which water had to be added. The products contained between 2 and 7 percent chrysotile — white — asbestos, mined in Canada. Both products were asbestos-free by 1977.

By the mid-1960s, investigators like Mt. Sinai’s Irving Selikoff had proved conclusively that asbestos was a cruelly efficient, though slow-acting, killer. Having already found high rates of lung cancer, asbestosis and mesothelioma among asbestos insulation workers, Selikoff and his colleagues began looking at drywall installers.

In a series of papers published from 1975 to 1979, they reported that sanding, sweeping or mixing joint compound could yield fiber counts up to 12 times higher than what was allowed under federal law. “Fiber concentrations generated by sanding were similar to those measured in the work environment of asbestos insulation workers,” they wrote.

In July 1977, having found “an unreasonable risk of injury of certain types of cancer, such as mesothelioma and lung cancer,” the Consumer Product Safety Commission said it intended to ban asbestos-containing joint compound. In a letter to the commission’s chairman, a Georgia-Pacific vice president said the company supported the ban, noting that “we ceased using asbestos in our product and switched to a substitute.”

The ban became effective in January 1978. The damage inflicted by asbestos, however, can take decades to appear. Microscopic fibers sent airborne by activities such as sanding dried joint compound can trigger lung cancer, asbestosis and mesothelioma. “There is no safe level of exposure known,” says the Environmental Protection Agency.

-------------------------

Don’t miss a single Center for Public Integrity investigation on the environment.

Sign up now to receive special newsletters relevant to your interest.

-------------------------

The government crackdown came too late for Daniel Stupino, a transplanted Uruguayan who began renovating New York apartments part time in 1974 and earned extra cash that way for nine years.

In a 2011 trial, Stupino testified that he regularly used Georgia-Pacific joint compound, among other brands, to seal joints between sheets of drywall. When he sanded it, he said, it was “like a snow … that penetrate[d] all over … in my body, my head, you know, my clothes.”

“What would you have done if you had seen a warning back then that breathing the dust from the joint compound is dangerous?” asked Stupino’s lawyer, Jerry Kristal.

“Not use it,” Stupino replied.

In the spring of 2010 Stupino began feeling “weak, tired,” he testified. “I didn’t know what [it] was, no idea. I thought it was stress.”

A CT scan revealed fluid in his lungs. “He make a hole between two ribs and he put [in] a drain,” Stupino said of his pulmonologist. What came out looked “almost like blood.”

The spirit-breaking news came shortly thereafter. The doctor told Stupino, “You have cancer, and it’s malignant. And I say, ‘My God.’ And [the doctor said], ‘Remember what you did 20, 30 years ago. Remember what you did.’”

Stupino had a lung removed in January 2011, then endured chemotherapy and radiation treatments that were “like hell,” he testified. “I have almost permanent pain.”

He said he’d once dreamed of retiring at 65 and traveling with his wife, Anna.

“Can you tell us what your dreams are now?” Kristal asked.

“I don’t have them,” Stupino said.

Stupino’s case against Georgia-Pacific settled mid-trial. He died of mesothelioma on Dec. 14, 2012, just shy of his 64th birthday.

Shares