She was sitting atop a pedestal when I saw her. With a silver coat, striped legs and spots along her back, she looked exotic. Maybe a Bengal. Except she was tiny. With one blue eye. When I poked my finger through the mesh encasement, she raised her nose to meet it.

Her name was Angelika, and she was a stray from a local shelter. But on the day that I met her she and a handful of other rescue cats had been brought to the White Columns Gallery, in Chelsea, to lounge inside a giant kitty play space that a pair of architects had designed for them using rubber, rope, and wood. Instead of rows of dreary cages, they were surrounded by paintings, video art, photography, collage and sculpture by artists like Elizabeth Peyton, Matthew Barney, Richard Prince and Andy Warhol, forming a collection of contemporary, cat-inspired art that was almost as engaging as they were. They even had a shrine. On a wall opposite from where they played, miniature cats made of china and plastic, with painted whiskers and round glassy eyes, crowded along a series of shelves. The way the lengths of the shelves tapered inwards towards the top made them look like a flattened pyramid, a winking monument to the art of collecting kitties.

I spent the better part of an hour exploring these works and returned to the play space uplifted by their lack of pretension (none of the works were labeled), their lively colors and the spirit of it all--how together they had transformed something as potentially creepy as cat love into a joyful, sophisticated moment. I watched a coffee-colored kitten bat a dangling feather, and a calico as it lounged along a rubbery, rope-covered branch, while visitors stepped inside one at a time to meet them--and hopefully take one home. That hadn’t been my intention in coming to the show. I already had two cats. Three would mean more litter, more shredded sofas, more dander and cans of food and a husband who felt duped because I hadn’t been a crazy cat lady when he married me. I hooked my fingers through the mesh. I knew I was high on the art, but Angelika seemed special, and when I couldn't find her amongst the others I felt my heart drop. Somebody else had taken her home. I turned to go and that was when I saw her, crouched inside a blue translucent cube that jutted beyond the play space atop a stack of more cubes, all in different colors. I tapped on the plastic. She looked at me and winked. Then she slinked down through the cubes, turning from blue to yellow to pink as she went.

“The Cat Show” opened in June, but had been conceived ten years earlier by Rhonda Lieberman, a curator, writer and artist, in a vacant lot in Long Island City. Every evening she and a group of neighbors would meet there to feed a group of strays. It was the 1990s; relational art was all the rage, but Lieberman says that watching those cats in that junk lot--their graceful, Zen-like movements--had been more compelling than any of the installations she was seeing at the time. She adopted one of those cats and her litter of kittens, and imagined replicating the lot as art, creating an atmosphere in which cats were celebrated and revered, not treated as throwaways.

It worked. Two weeks later, I swallowed my doubts and brought Angelika home as a “surprise.” As expected, my cats hissed. My husband did, too. A third cat? "Grey Gardens" alert! I tried using her looks to rationalize my decision: “But look how tiny! Look how striped! Look at her one blue eye!” My husband crossed his arms, and even though I knew I would not give her up, I also knew he was right to be upset. I was embarrassed for myself. I hadn’t gone to a shelter. I had gone to a Chelsea gallery, and come home with a one-eyed cat. In a way, it seemed as unlikely as “The Cat Show” itself. In ten years of trying to get the show made, Lieberman had given up the idea at least once. That it happened at all, she believes, was due to the success of the Walker Museum’s Internet Cat Video Festival, whose inaugural show in Minneapolis in 2012 (this year it spread to multiple cities) drew a crowd of 10,000 people, sparked a viral sensation and likely made the idea of inviting strays into a white pristine space more palatable to gallerists.

Since then, two more cat-inspired exhibits have opened in New York City. "Divine Felines," at The Brooklyn Museum, explores the role of the cat in Ancient Egyptian life; "Cats and Girls," at The Met, features portraits of cats and girls by the French painter Balthus--which has made me wonder if my rash decision to bring home a cat was not so rash at all. I wondered if art could help me diagnose my cat-collecting obsession. Was there something about cats--the way they looked, the way they moved--that we were hard-wired to appreciate? Even if they couldn’t explain why I had gone behind my husband’s back and adopted another cat, could these shows help explain why we find cats and their memes so compelling?

I went to see “Divine Felines” in August, shortly after it opened. Since the Ancient Egyptians were the first to domesticate the cat around 4000 B.C., at about the same time they began using granaries, I hoped their art might shed some light on the origins of cat worship. I wasn’t disappointed.

The relationship between cats and humans began for pragmatic reasons. By killing vermin, cats protected the granaries, and by extension, families' livelihoods. They came to be admired for other qualities, too: for being prolific, vigilant mothers; for loving the sun but hunting at night; for their curious habit of lying in open doorways; for the way their heads were capped by a pattern of stripes that resembled the shape of a scarab, the beetle that in Ancient Egyptian cosmology symbolized the heavenly cycle of the sun. These earthly aspects became iconographic, and by 1000 B.C., the Egyptian pantheon was populated with gods and goddesses that had been fashioned in the image of the cat. Cults had sprung up around them. Relics and sculpture were fashioned.

In a small red room that linked the Egyptian wing to a mezzanine filled with European paintings, about 30 objects from the permanent collection had been arranged into three different groups: domestic cats, fearsome lions and magical relics. Together, they told a creation story of sorts--the rise of the cat in ancient Egyptian life. There was a statuette of a mother cat nursing her kittens, ears pricked and alert; a large wooden cat whose head had been anointed with a glistening rock crystal scarab; an amulet of Bes, the lovable dwarf god who chased away demons. But most compelling of all were the sphinxes: part human, part cat, made of bronze or stone. Shown slaying serpents, unleashing chaos on the world, or accompanying souls in moments of dangerous transition, like childbirth or death, they were fearsome-looking objects, fusions of humans and cats, the ultimate symbol of just how close we’d become.

That these cats were revered for their contradictory aspects--fertility goddess and demon-slayer, underworld travelers, borne of the sun--was no coincidence. In a dualistic cosmology (the scarab, after all, was just a bug that rolled dung into balls), the cat helped make sense of an uncertain world. In "Sexual Personae," her book about the aesthetic principles of decadence, desire and art in Western culture, Camille Paglia argues that cats became “the model for Egypt’s unique synthesis of principles.” She describes them as “chthonian...amoral...androgynous...narcissistic…” and as having “a natural sense of pictorial composition: they station themselves symmetrically on chairs, rugs, even a sheet of paper on the floor.” She calls them “arbiters of elegance--that principle I find natively Egyptian,” and compares them to Baudelaire: “The cat...is a dandy, cold, elegant, narcissistic, importing hierarchic Egyptian style into modern life.”

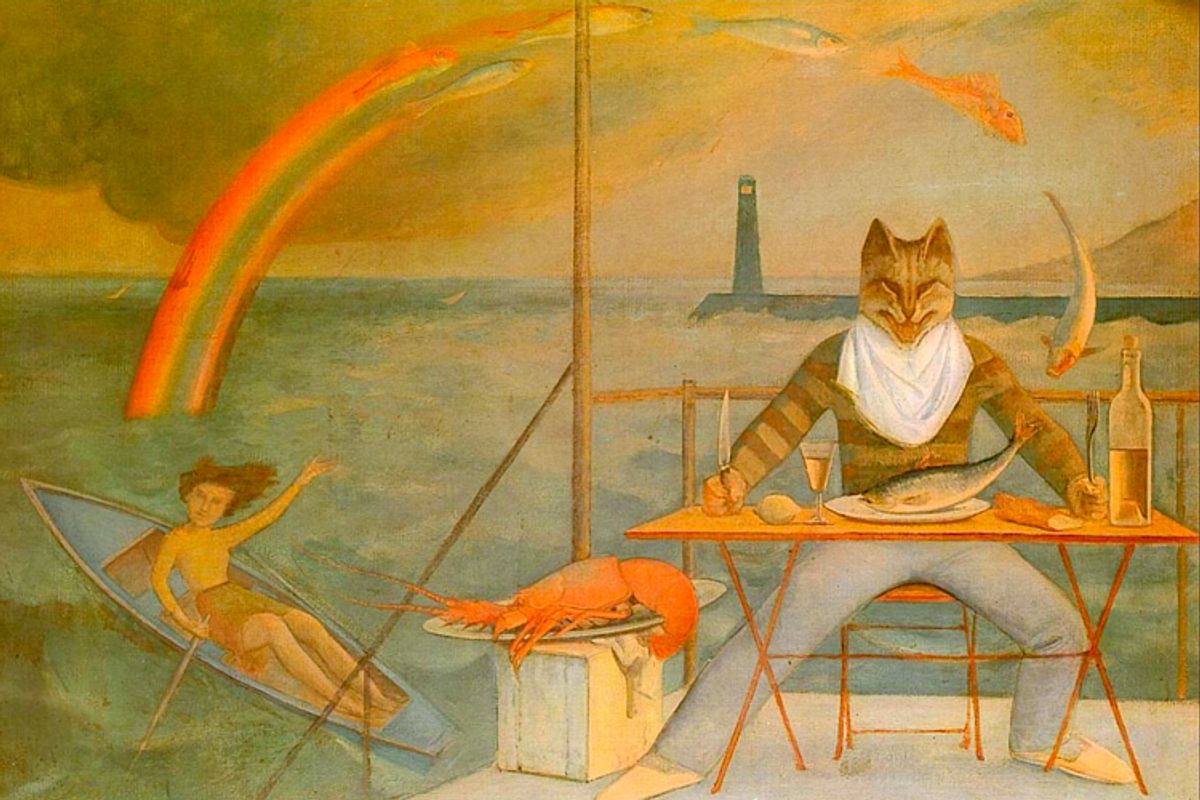

I had read Paglia’s book in advance of visiting “Cats and Girls,” which opened a couple of weeks ago, and as I looked at the paintings by Balthus, I thought I could see what she meant. His cats, painted in oil on canvas, were cool and detached. They possessed as much elegance as any of the sculptures in “Divine Felines,” only now, instead of hunting mice or slaying demons in an ancient, pantheistic world, they posed in fashionable rooms, where they lapped milk from bowls, chased balls of twine or stared into space while young girls struck up erotic positions around them. The connection between the girls and the cats seemed formal as well as spiritual. They gave the paintings their symmetry, and like mirror images, one appeared as insouciant and self-absorbed as the other. Together, they were, in Paglia’s words, “the least Christian members of the household.” Yet despite this connection, they also seem worlds away. Disinterested. Alone. In some frames, the cats weren’t there at all, although the girls still reached out to caress or play with them.

Paglia had made the connection between ancient and modern aesthetics, via cats. And Balthus had split the sphinx, sundering cat from girl. I wondered if I could go further. If cat memes had made it this far, what had stopped them from replicating and mutating themselves right into the post-modern world? It amused me to think that if Balthus’s cats were dandies, then Lieberman’s strays were like avant-garde performance artists, upending the grip of formalism, that “hierarchic style.” Had their performance created a virtual space in which I had become as connected with the cat, and let’s face it, as narcissistic, as the girls in Balthus’s paintings? I imagined Maru, part cat, part box, as a modern-day sphinx, and Grumpy Cat as a dwarf god who chases away the modern-day demon of office ennui. Could they be the latest iterations of a visual meme that has been evolving and thriving for 6,000 years?

I stopped myself. This was all conjecture, the fluffy musings of a cat-meme-soaked mind. According to evolutionary psychologist Richard Dawkins, in his book the "Selfish Gene," for a unit of culture to thrive it needs more than just “fecundity” and “longevity”. It needs copying-fidelity. Forms and styles may mutate, but it has to have that something that makes it stick in our brains and matter. If their hierarchic style had been subverted, what of those ancient cats still remained?

This question weighed heavy on my mind when I walked into the exhibition’s final room and saw them. Forty ink drawings Balthus had made as a child. Displayed in a glass case, they told the story of Mitsou, a cat that Balthus had rescued from the streets. In the drawings, he and the cat go everywhere together. They paint, chase mice, have adventures. When Balthus falls sick, Mitsou stays by his side, but eventually grows impatient and runs away. Balthus never finds him. The final drawing in the series shows the artist crying alone in his room.

These drawings so impressed the poet Rainer Maria Rilke with their composition and drama that he got them published in 1921 and wrote the foreword for the book (he was a friend of Balthus’s mother). They also cast the show in a different light.

As I walked back through the show, I saw the paintings anew. The cats seemed less an amoral, devious, voyeuristic presence--less chthonian--than a symbol of something lost that could never be recaptured. If, in the paintings where they didn’t appear, cats had seemed like a formal device to manipulate the girls into erotic positions, they now registered only as absence, the ghostly place where a cat used to be.

I thought of my cats at home: Angelika, Dot, and Fermina. If to lose a pet is to suffer a particular kind of heartbreak, Balthus had captured the sorrow of never knowing what happened, of never saying goodbye.

The obvious thing struck me then. As working animals, pets, or strays, cats were companions before there was God. That their memes have been successful is less because of how they look, than because they take our everyday interactions with these animals and transform them into something that endures -- a relic, a story, a performance, a virtual experience that makes us feel pleasure or pain. And that in the continuum of cats in art through time, these forms and experiences had evolved in conversation with each other. By creating a space where people like me could interact with cats, and see them afresh, “The Cat Show” had provided more than an aesthetic solution to the social problem of strays in New York City. It gave resolution to Balthus’s sorrow. A silvery stray, with a scarab of stripes on her head, had finally found her way home.

Shares