I used to think Lou Reed was a professional wrestler.

I caught one of my first glimpses of him when I was a teenager, on the cover of his 1989 album “New York.” Five versions of the man stand against a stark brick wall, each a different character from a song or iteration of his persona: one wears a long duster like an urban cowboy, another a muscle shirt and leather pants. Several of these Lou Reeds sport mullets, one lights a cigarette, another hides behind shades stolen from the set of “They Live.” Each Lou looks supremely pissed off and antagonistic. Maybe it’s the size of his name in all caps, but they all look like they’re ready to body-slam anyone who’s not a Yankees fan. For a kid who didn’t know what a Velvet Underground was, the imagery struck my adolescent eye as more WWF than “120 Minutes.”

Today “New York” is not the obvious point of entry into Reed’s large catalog, but “Dirty Blvd.” ushered me into this intriguing world. The video, a staple of late-night MTV, drew me in with its black-and-white shots of a kid (in the song his name is Pedro) wandering the streets of a bleak and unfriendly city, interspersed with Reed playing guitar and lip-syncing. The song itself assembles its tense momentum by wiring guitars together and adding a car-alarm drumbeat; it’s rock 'n' roll stripped bare of parts and left to rust in the gutter. Reed’s singing, if it can be called that, isn't pretty at all — and even as a teenager I understood that that was the whole point. Dirty Boulevard was not a pretty place to be, and life was so extreme that its inhabitants had little time for artifice or prettiness. Despite the narrative nature of its video, “Dirty Blvd.” was not a story-song so much as it was a setting-song: Reed wanders up and down that seedy thoroughfare like a tour guide pointing out the worst sites in the city. “This room costs $2,000 a month, you can believe it, man, it’s true,” he says, matter of factly. “Somewhere a landlord’s laughing till he wets his pants.”

There is something about those lines — not merely what they describe but the way Reed delivers them, with no regard for melody or rhyme or any other niceties of songwriting — that struck my small-town self as being markedly different from everything else I was hearing on the radio and MTV at the time. Reed didn’t flinch from describing hookers offering blow jobs to cops or from calling out the hollow symbolism of the “Statue of Bigotry.” Here was a song with real stakes rather than a catchy hook, with a sense of lived experience and a need to depict this world accurately, even if that meant dwelling on its ugliness. It’s precisely that determination that gives the final verse of “Dirty Blvd.” its almost triumphal sense of yearning, as Pedro finds a book on magic in a garbage can. “‘At the count of three,’” he says,"‘I hope I can disappear and fly fly away, from this dirty boulevard.’”

Just as I suspected Reed might be a fighter, I also assumed that every street in New York was a dirty boulevard. Naive yet bookish, I was growing up in a small town in West Tennessee, and while I had done some traveling and some reading, the city still seemed as foreign to me as the moon itself. It wasn’t until I actually moved to Queens that I understood New York as a place with an infinite variety of circumstances and experiences. But Reed had depicted the setting so vividly that I began to understand that the picture he paints is true enough.

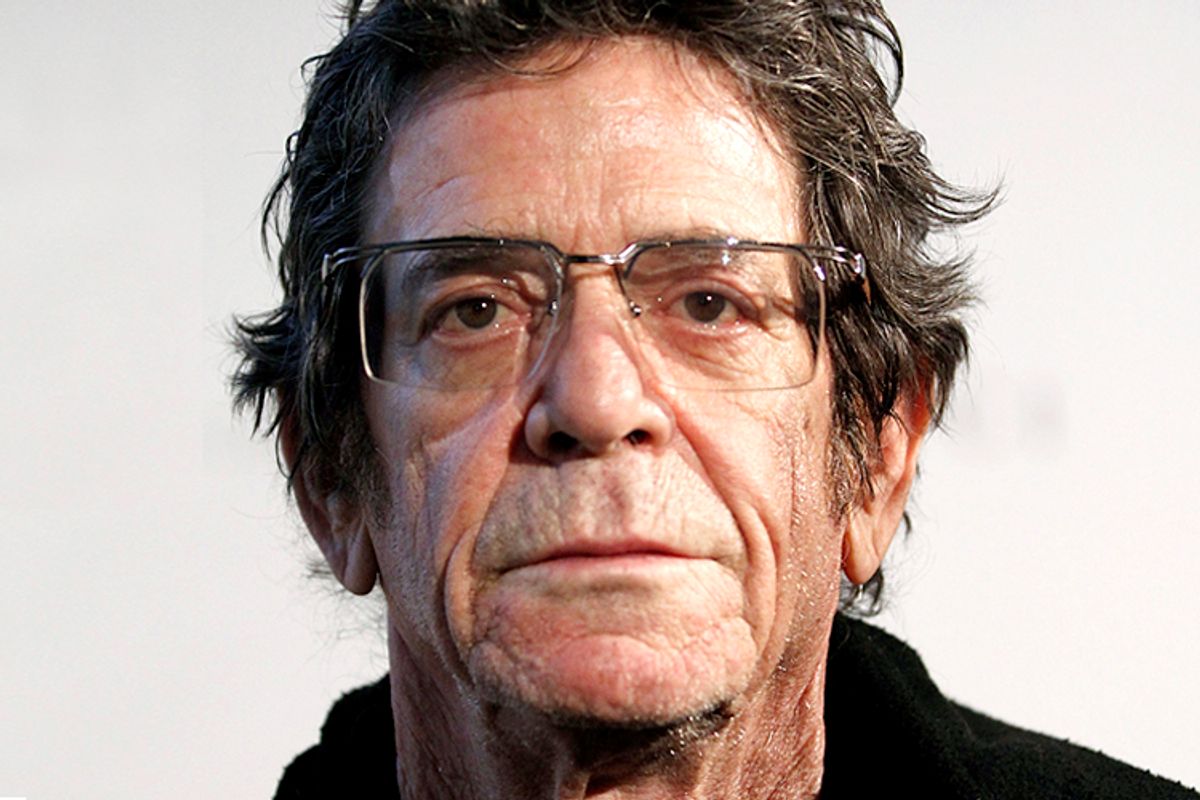

I find it difficult to calculate the impact Reed had on me at such an impressionable age. When I heard he died on Sunday, after complications from a liver transplant, my first thoughts were of my 15-year-old self listening to “Dirty Blvd.,” which I now understand is not a major entry in his catalog. In addition to prizing empathy and compassion for those whose experiences do not overlap with our own — a useful tool for any aspiring writer as well as for any citizen — the song introduced me to a very particular form of songwriting that prizes the specific, the local, the immediate, and conveys it all in concrete details and personal, if not strictly autobiographical, observation. Reed is not, of course, the only artist who could have taught me this lesson; had I discovered Randy Newman or Warren Zevon sooner, or had I heard Springsteen before “Brilliant Disguise,” I might have learned something similar from them. Nevertheless, today I tend to gravitate toward lyricists who eschew direct confession and instead depict their worlds with similar insight, exactitude and wonder: Patterson Hood in the New South, Kendrick Lamar in post-NWA Compton, Craig Finn in the Twin Cities, Dylan in mythic America. None of them sound much like Reed, but each sends detailed dispatches from their respective realms, acting as much like documentarians as musicians. In that regard, Reed was the first rock star I associated with a place.

Of course, it would take me years to fully appreciate Reed’s particular style or to understand what made “Dirty Blvd.” significant within his larger body of work — how it served as a natural extension of the subject matter he had been exploring since his first notes with the Velvet Underground in the late 1960s or how “New York” was his most conceptually cohesive album in a decade, a throwback to the records that had established him as New York’s gutter poet (he actually studied at Syracuse with Delmore Schwartz). When I got to college, the Velvet Underground were inescapable. It was impossible not to hear them, especially since pretty much every subsequent rock artist cited them as a defining influence. Andy Warhol may have been the conceptual mastermind and John Cale the musical one, but Reed’s lyrics usefully shifted rock’s subject matter toward the gritty urban verisimilitude of Hubert Selby Jr.: junkies, prostitutes, rent boys, transvestites, cross-dressers, and assorted perverts.

On 1967’s “The Velvet Underground & Nico,” as the band pound out an impatient, fidgety beat on “I’m Waiting for My Man,” Reed evokes the visceral agitation of a junkie venturing into a rough neighborhood to meet his seller, and he depicts a parade of locals to reinforce the alien nature of the first-person character: “Hey white boy, what you doin’ uptown / hey white boy you chasin’ my women around / Pardon me, sir, it’s furthest from my mind.” You could argue that Reed is exploiting non-whites to reinforce the dangers and degradations the narrator is willing to endure, and you wouldn’t be wrong. On the other hand, “I’m Waiting for My Man” subtly portrays him as an invading force, an interloper whose habit disrupts the patterns of this community.

When Reed left the Velvet Underground in 1970, he decamped to London, yet he didn’t abandon New York City as his primary subject. Musically, however, he began to move away from the drone and dissonance of the Velvets. His second solo album, 1972’s “Transformer,” displays a newfound diversity, tweaking some of the melodic and stage conventions of glam rock. It’s arguably his most commercially successful album, and several songs ended up on soundtracks, most famously “Perfect Day” on “Trainspotting.” (To show just how far Reed’s influence extends, “Mystery Science Theater 3000” named its spaceship the Satellite of Love, after a song on “Transformer.”) The album also included an honest-to-God radio hit, a bleak tableau vivant that includes a cross-dresser named Holly and a prostitute named Candy, among others. “Walk on the Wild Side” may be the least likely hit of the 1970s, and not just because of its subject matter. It’s built on a shuffling jazzbo rhythm anchored by a brooding pendulum bass line and interrupted by a sax solo that sounds like you’re hearing it from two alleys over. U.K. censors were not familiar with some of Reed’s references, so for a while the lines “But she never lost her head even when she was giving head” went unbleeped on the radio.

During the 1970s, grimy, bankrupt New York City was a popular subject in cinema, inspiring interpretations that ranged from the innocuously exploitative “The Out of Towners” in 1970 to the dire, overrated “Taxi Driver” in 1976. Reed wasn’t exactly celebrating the dangers of the city, yet he rarely exploited them for cheap sensationalism. Rather, he sounded like he was speaking from some grubby street corner, at home among the freaks and weirdos even as he normalized what made them freaks and weirdos. In this regard, his stoical sing-speak was crucial to portraying his fringe characters as human and humane, if only because he presented himself like such a character. His delivery sounded like a response not to the city, but to people like the narrator of “I’m Waiting for My Man” — people who come to the city as outsiders, whether for nefarious reasons or simply to judge its inhabitants. Rather than acting defensive, he simply sounded matter-of-fact, like someone who did not suffer fools or tourists. In interviews, he was notoriously curmudgeonly and caustic, often resorting to one-word answers or outright antagonism.

Most artists can’t survive such a breakneck shift from the underground to the mainstream, but Reed knew he was just visiting the pop charts. Perhaps because he never attained the same level of celebrity as, say, David Bowie or even Patti Smith, he never lost his grasp of the seedier side of New York, even as he moved on to more personal statements on 1992’s “Magic and Loss” or to more literary projects like his notoriously panned 2011 Metallica collaboration “Lulu,” adapted from a play by German writer Frank Wedekind. In the meantime, his city got cleaned up. The denizens of “I’m Waiting for My Man” and “Walk on the Wild Side” were priced out of Manhattan and gentrified Brooklyn. The grindhouses of Time Square were replaced with Disney Stores and TGI Fridays. That dramatic civic transformation today lends Reed’s early albums a sense of street-level reportage and his later ones a dire solemnity, as though he’s delivering a eulogy.

As he aged, Reed’s wizened stoicism continued to intensify, almost to the point of self-parody, but he never sounded disengaged or remote. Even as his contemporaries mellowed into late-career standards-bearers or rote recitalists, Reed came across as unusually guarded and careful, as though measuring out exactly how much of himself he wanted to give over to the world. His health problems complicated that equation considerably, although he combated illness with tai chi, yoga, bodywork and most recently a full liver transplant. “Hudson River Wind Meditations,” his 2007 album of ambient “ordered” music, sounded like his most revealing album in years.

Reed made what is perhaps his most personal statement about the precariousness of life on “What’s Good,” a standout from his 1992 album “Magic & Loss.” Following a heraldic guitar fanfare, the lyrics sound almost playful in their surrealness: “Life’s like a mayonnaise soda, and life’s like space without room / life’s like bacon and ice cream / that’s what life’s like without you.” Yet, Reed sneaks in small clues that sound all the more devastating for the scrambled imagery around them: “You loved a life others throw away nightly / it’s not fair, not fair at all.” “What’s Good” never comes to any settled conclusion about anything in particular; instead, it’s hauntingly open-ended. If “Dirty Blvd.” was the first song I thought of when I heard of Lou’s death, “What’s Good” is what I’ll be listening to for several days to come.

Shares