It's a testament to Hannah Arendt's "Eichmann in Jerusalem" that "the banality of evil" remains one of our most enduring clichés, a convenient shorthand not only for bureaucrats but any "ordinary" person complicit in a state's war crimes. For readers of "Hitler's Furies," Wendy Lower's chronicle of German women's participation in the Holocaust, this trope is especially alluring. Like the subject of Arendt's book, many of these women were "desk murderers" -- secretaries and administrators whose weapon was not a Luger or a gas chamber but a typewriter used to execute Hitler's Final Solution.

And yet despite these similarities, the analogy ultimately proves imperfect. Unlike Arendt's portrait of Adolf Eichmann, itself challenged by academics like David Cesarani, Hitler's furies were not ideologically neutral. Neither were their crimes confined to an office or a classroom. As Lower reveals in chilling detail, they were also capable of the same savagery as their male counterparts -- a fact often overlooked by Holocaust scholars and historians.

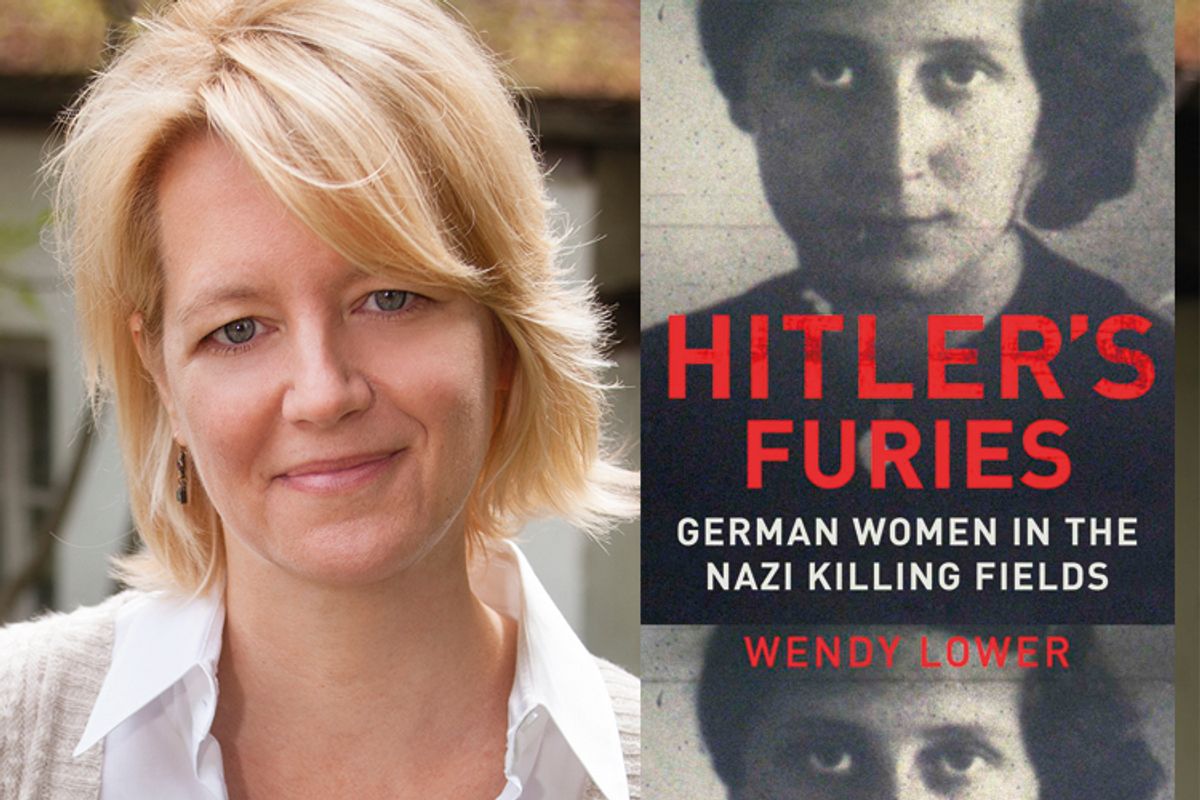

Lower, whose book is a finalist for the National Book Award, spoke with Salon over the phone about the parallels between Eastern Europe and the American Wild West, how Nazism offered its own form of sexual empowerment and what motivated these women to commit such atrocities. What follows is a transcript of that conversation, edited and compressed for clarity.

Some of the most arresting passages in your book are your descriptions of these women's lives as colonizers in Eastern Europe. It seems like you're very deliberately using the language of the Wild West and all the lawlessness associated with it. What kind of effect did this displacement have on their behaviors?

Heinrich Himmler saw the Eastern frontier as Germany’s manifest destiny, and in some of his monologues, Hitler actually refers to the Native Americans of North America and how they disappeared. They considered the loss of native populations as a normal part of empire building. In the Wild East there was a sense that anything was possible, and new kinds of roles and character types were tested out, occupied and inhabited. Secretaries like Johanna Altvater operated like cattle-herders in the ghetto. She's actually described as wearing short pants like a Western cowgirl -- a counter to the domesticated hausfrau with a skirt. The Nazis wanted to enforce a kind of femininity in dress, and yet the behaviors of these women defied preconceived notions of femininity.

How much of their involvement in Nazism was a product of their youth? You note that they came from disparate socioeconomic backgrounds, but that most all of them were in their 20s and early 30s -- and they all came of age during Hitler's rise to power.

I mean, the entire Nazi movement -- and fascism more generally -- is about a call to youth. In the case of the Nazis, the racial element was especially strong, and there was a tremendous focus on reproduction, vitality and fertility. It was also about utility and who could be co-opted for some of these experiments. Single women between the ages of 17 and 25 had to complete compulsory labor service, so already the official policy was to draw on that demographic to work as secretaries, nurses and teachers in the East. And because these women weren't tied down with families, they had the flexibility to go. Coming out of grammar school, they saw this as an opportunity to make something of themselves before they settled down, or to find a mate in their workplace abroad.

For some of these women, it seems like the movement was simply an opportunity to advance themselves socially.

I think we tend to underestimate how important class was to how these women identified themselves. The regime of the Kaiser had been dismantled and discredited by the First World War. Suddenly women were allowed to vote, to participate, to escape the stifling atmospheres and villages where they were forced to work as sheep herders. The natural avenue for this kind of mobility were "female" professions like nursing, teaching and secretarial work, and so those are the main areas where we see women make their way through the state system.

And of course all of this is coinciding with the rise of the modern workplace.

Exactly. So much of the literature on this subject has addressed fascism as the rise of the modern state, and all the state-building that went along with it. And yet women’s history is often left out of that. One of the challenges of the book was to address this notion of female innocence. Women were very much a part of the inner workings of the state, and the state is an identified operation in terms of war-making and the Holocaust. So you can’t have them participating in the growth of the state and not have them involved in the history of these policies and crimes.

Why are women left out? How do you account for this gap in Holocaust studies?

I think what has happened is that Holocaust studies have developed along one track, and women's studies within the frame of Nazi Germany is developing along another. I don't want to overstate the role of women as killers because clearly the killing was primarily perpetrated by men. The male leadership organized it and decided upon the policy and so forth. That study of the Holocaust started with a focus on those who were most responsible, those whose actions were easily documented. So our history reflects that.

What I found really surprising is that much of the testimony I use in my book has been available to scholars for years. And it struck me when I went through the material that female testimony often wasn't questioned by prosecutors. Why were women so knowledgeable about the systems developed to implement mass murder and the killers themselves? How is that they are able to give this testimony to begin with? They're right there in the scene.

So setting aside the prosecutors of these trials, is it a failing on the part of historians that they haven't explored some of these questions further?

I don't want to point any fingers because there are so many questions you can compose. Everyone goes to the Holocaust archives with a different question. You could say a couple of years ago, "How come we didn’t notice the Polish presence?" How could we have missed the big story of local collaboration when we have so much testimony and visual evidence of that?

Access is another issue. For example, I would argue that my book could not have been written prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union. Regional archives gave me a better sense of the open air mass shootings, the way that the killing happened outside of the camps, how entire communities evolved and were witnesses to this, and how many people had the possibility of participating. These things emerge at certain times because we have access to new information. I could go back and look at the traditional evidence with new eyes.

Returning to the book, in one of your chapters you examine this idea of "Ostrausch," or Eastern rush. How did Nazism offer its own form of sexual liberation?

There was an exuberance that came with participating, a sense of adventure. All of the shame from the defeat in the First World War was being overturned, and the energy, idealism and utopianism that was part of this Eastern expansion was especially energizing for women. A sexual revolution had begun during the Weimar period, and this became one of the tensions of Nazi Germany: Women were treated as biological objects and pressured to reproduce, but of course reproduction involves sex and sex is pleasure. So there was a lot of promiscuity, and a lot of children born out of wedlock. Members of the SS were constantly swapping partners -- and this was all considered OK. And of course this release of sexual energy is intersecting with acts of incredible violence. Participating in a crime together offered its own form of intimacy.

My one lingering question is what distinguishes the women who worked as secretaries or teachers in the regime from those who were actually pulling the trigger? Was it simply a matter of opportunity?

Numerically there's a concentration of SS wives among the perpetrators. Being in such close proximity to power is something I think was important, especially for women who wouldn't have otherwise tasted what it was like to be a member of the elite. You have these farm girls who suddenly have a license to kill, many of whom are acting out in front of men in small German-only communities. We don't really see women committing violent crimes under the pressure of other women.

Ultimately, I don't have the evidence to ascertain just how assertive and aggressive one person might have been as opposed to another, but I imagine the violent behaviors of these women were a product of their individual characters. When asked about Johanna Altvater [who beat an infant to death with her bare hands, among other violent crimes], one of the prosecutors said she was "someone you would not want to encounter on a moonless night."

Shares