I recently attended a lunch with a group of women to talk about food and health. I’d come to the conclusion that my health would be better served doing this than talking to my doctor. He was unable to answer questions about studies that included women participants and how the findings might differ from the research he was citing, all of which only studied men. I now have a new doctor and we get along just fine.

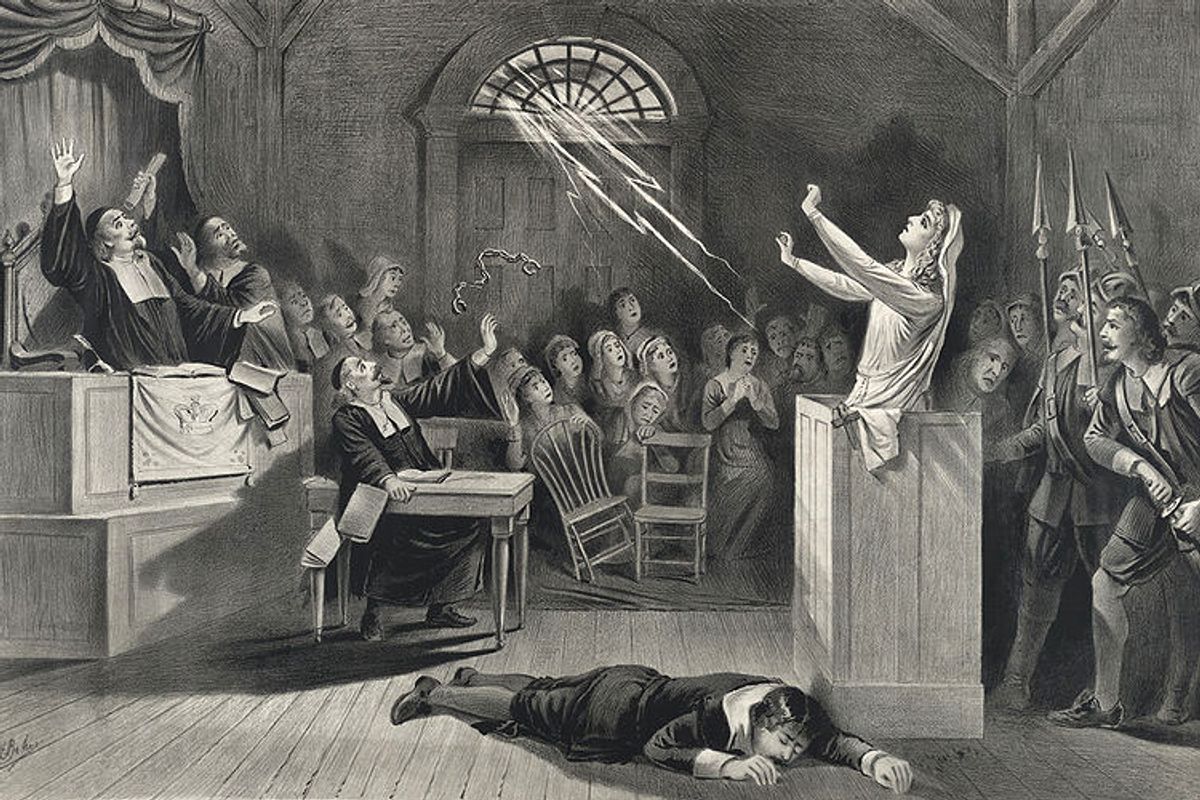

Less than 400 years ago, I, and every woman at that lunch with me, might very well have eaten our heart-healthy meal then been merrily immolated as a coven of witches. There we were, taking about herbs and using our senses to achieve healthy outcomes. Maybe salad dressing is a potion. Who knows.

As Barbara Ehrenreich and Deirdre English explain in the 2010 revision to their classic book “Witches, Midwives & Nurses,” between the 14th and the 17th centuries, tens of thousands of people were killed as witches. Estimates range, but the latest scholarship puts the number at roughly 100,000 people, 80-85 percent of them women. By the mid-16th century there were villages where all but one woman had been killed for practicing witchcraft.

The 400-year period of witch panic was rife not just with misogyny, but with political and class struggles that created a petri dish for people to act on it. It was a time of massive social upheaval, marked by the Reformation and the rise of capitalism. While the Catholic Church is sometimes blamed as the sole instigator of witch trials, Protestants and civic authorities were central to the elimination of women accused of “dark magic.” As Salon's Laura Miller put it in an essay on the topic, “It takes a village to burn a witch.” Or 100,000 of them.

What were these women burned (also strangled, hanged and beheaded) to death for? Well, first, charges often amounted to condemnations of being female and sexual, two qualities that even today, religious fundamentalists of all stripes tend to deplore. Elaborate fantasies about women engaging in intercourse with the devil were a regular feature of witch trials. Second, women were persecuted for associating with other women, accused of forming covens or holding parties with Satan. Women who came together to celebrate holidays or to share information, trade herbs, gossip or otherwise, you know, hang out together were considered dangerous. Third, women were punished for being poor and helping the poor. As Ehrenreich and English point out, the church was inclined to instruct the desperately impoverished, who made up the vast bulk of the population, to bypass the ministrations of women healers and look to the afterlife for solace while, at the same time, supporting medicine and medical help for the nobility. “Male, upper-class healing under the auspices of the medieval church was acceptable, female healing as part of a peasant subculture was not,” Ehrenreich and English explained. Fourth, they appear to have been particularly maligned for providing obstetric support and for using empirical reasoning. Lastly, women were charged as witches because they were successful. Take the case of Jacoba Felicie, who was tried in 1322. Her accusation read, “she would cure her patient of internal illness…visit the sick assiduously and continue to examine…in the manner of physicians.” No less than six witnesses described how she’d successfully treated the when “doctors” had failed. This was evidence against her, by the way.

Why did the time-of-great-transition panic manifest itself with such unrelenting misogyny? The period of witch hunting coincided with several simultaneous challenges to the “natural” world order – religious, social and political, including, very importantly, traditionally prescribed gender roles.

The rise of Protestantism represented a revolutionary challenge to the church in many ways, not the least of which was in its redefinition of women’s roles. While Protestantism confirmed women’s individuality and autonomy in matters of faith, it also rapidly renewed focus on women’s domesticity and provoked debate about and rejection of the notion of women as leaders (during a time when Elizabeth I was Queen). In 1558, John Knox wrote “The First Blast of the Trumpet Against the Monstrous Regiment of Women” to explain why the Bible made it clear women could not and should not lead. Fifty years later William Gouge’s popular “Of Domesticall Duties” detailed why wives should be subservient to their husbands and the father figure should be "a king in his owne household.”

At the same time, the rise of commerce and a commercial class led to a greater focus on gender differentiation and hierarchical sex-based work. Women, unpaid and paid, fueled the agricultural labor market while being restricted in commercial endeavors.

In addition, as Ehrenreich and English explain, a newly developing male medical profession benefited economically from the demonization of female healers and midwives, many of whom were poor and derived their only income from healing. Not only was the division between “witches magic” and “men’s medicine” gendered, but also it was classed. Newly minted male-only university doctors in the employ of the nobility were happy enough to eliminate illiterate female competition for their services. Professional doctors could not, however, act alone in violence against women who presented challenges and obstacles. Widespread witch hunting required that the church, the state and the medical profession come together in agreement and lend institutional support and leadership to the petty squabbling and vendettas of neighbors that often fueled witch hunts. Similar themes can be seen in the Salem witch trials.

The church, first Catholic, and then also Protestant, came up with elaborate reasons for suppressing the influence of wise women and female leaders. Central to witch hunts of the time was the oft-cited “Malleus Maleficarum,” without a doubt, one of the more misogynistic and influentially destructive texts ever written about women. Its purpose was to educate people about women’s inherently base, craven and evil natures. Heinrich Kramer, a German prelate, published it in 1486 and it became the inspirational text for centuries of witch hunts. The Malleus Maleficarum made connections between midwives, wise women and witches, and these appear, in turn, in trial records from the period. The text took pains to distinguish between the medical “profession” from which women were barred (they could not attend university, study, train or otherwise receive qualifications) and the “demonic” healing work and knowledge of laywomen and midwives. “No one,” it explained, “does more harm to the Catholic Church than midwives.” This might go a long way to explaining why today, in Sweden, one of the most secular countries in the world, midwives thrive and the gender gap between men and women is among the smallest in the world. It is rated the second best country in which to give birth and become a mother.

It’s also important to note that the peak period of witch hunting was the 17thcentury, when both the Enlightenment and the Scientific Revolution posed great challenges to religion's dominance. Women healers whose powers and successes were based on empirical study presented many layers of threat. Instead of faith, “witches” derived conclusions from their study and applied their knowledge accordingly (often to far greater success than university-trained doctors). The church was not interested in women who were effectively practicing observation-based science and providing alternatives to faith-based “medicine.”

Older, assertive, knowledgeable, authoritative and respected women were not welcomed in a fast-changing world in which many forces were aligned against them. They were a constant challenge to men’s power. This appears, still, to be a problem for some.

The effect of all of this was to cull women from medicine and care, except as handmaidens. The long-term result was male-dominated medical profession that, while changing, is still with us. In the United States a mid-19th-century American Popular Heath Movement was driven largely by women, especially working-class women, trying to find ways to develop preventative care so that they would not be subject to loopy medical “cures.” During that time the medical profession was increasingly monopolized by upper-class, educated white men, a situation only now changing. The first medical school in the United States waited 80 years before admitting a woman in 1874. In 1910, an evaluation of medical schools resulted in the closing of six out of eight schools for African-American students and most schools that allowed women. Midwifery in particular was targeted as dangerous and unprofessional, a particularly damaging effect considering that poor women, and especially African-American women in the South, relied on midwives almost entirely for medical care. As recently as 1970 women made up only 7 percent of U.S. doctors. It was not until 1989 that the AMA named a woman to its board. Today, women make up 30 percent of doctors, primarily white women, but still more than 91 percent of all nurses. The percentage of men who are nurses has tripled between 1970 and 2011. In the past two decades women have made monumental strides in the medical profession, despite which they face obstacles in pay, tenure and leadership.

However, one of the real lasting and harmful legacies of this history is that, in 2013, women’s health and reproductive rights remain stubbornly under the influence of conservative, religious men, from Todd “women’s bodies have a way of shutting that down” Akin to Sheikh “driving hurts women’s ovaries” Saleh Al-Loheidan, with zero understanding of science, medicine, biology or, really, modernity.

Amazingly, this week, I could not easily find a doctor costume for women. Not even a sexy one. Lots of nurses and witches, however. The truth is, witches loom large in our imaginations and remain a source of fear for too many people. Anyone who doubts that this is the case should consider that Erica Jong’s most banned book is not the "Fear of Flying" of “zipless fuck” fame, but her 1999 illustrated compendium "Witches."

My former doctor is a living example of a problem with deep cultural and historical roots. During our conversations it became evident that he had never taken the time to consider why men’s bodies might not be the standard by which to gauge women’s or why basing prescriptive decisions for women on male norms was a problem. How this can still be the case is astounding. Indeed, he argued with me, because how could I, a non-doctor, presume to have greater insight into my own health or feel that expressing curiosity about bodies like mine was a legitimate route. As I left his office for the last time, I thought to myself, “Women like me are the daughters of the ones you didn’t burn.”

Shares