In a move foreseen for months, even years, the New York City Opera filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy on October 1. The company Mayor LaGuardia famously dubbed the “people’s opera”—from the New York Mets to the Met Opera’s Yankees—was dead after 70 years of dramatic service. Gifted with a predictable demise, the best a host of death-watching reporters could devise was a “Fat Lady Sings” riff. Not even NPR was immune from this deficiency of wit and wisdom. The City Opera ended not with a whimper but a guffaw: a shrug of the shoulders to an institution many of us knew little of and few cared much about.

It’s that easy to lose a cultural institution; the mourning period was short lived at any rate. Because did we really need another major opera company when we already have the Met? It’s a question about vitality, richness, diversity—you could just as well ask: Did we need the dodo? And aren’t they similar questions? In fact, aren’t they asking the same questions: What do we need? What are we willing to lose?

Because we can lose a river dolphin species, we’re losing hundreds of frog species—and now we’ve lost the City Opera. Life will move on and so will we, no worse for the wear (at least so it seems). The end of the opera and the extinction of a species are oddly related. It’s a question, ultimately, about disposability and conservation. Save the whales! Save the opera?

The sad truth is that much of the City Opera’s fall was self-inflicted. Years of fatal mismanagement, bad decisions—cancelling the 2008-9 season among the worst—and diminishing sales—down 87 percent in 2011-12 from 2005-06—impoverished the company.

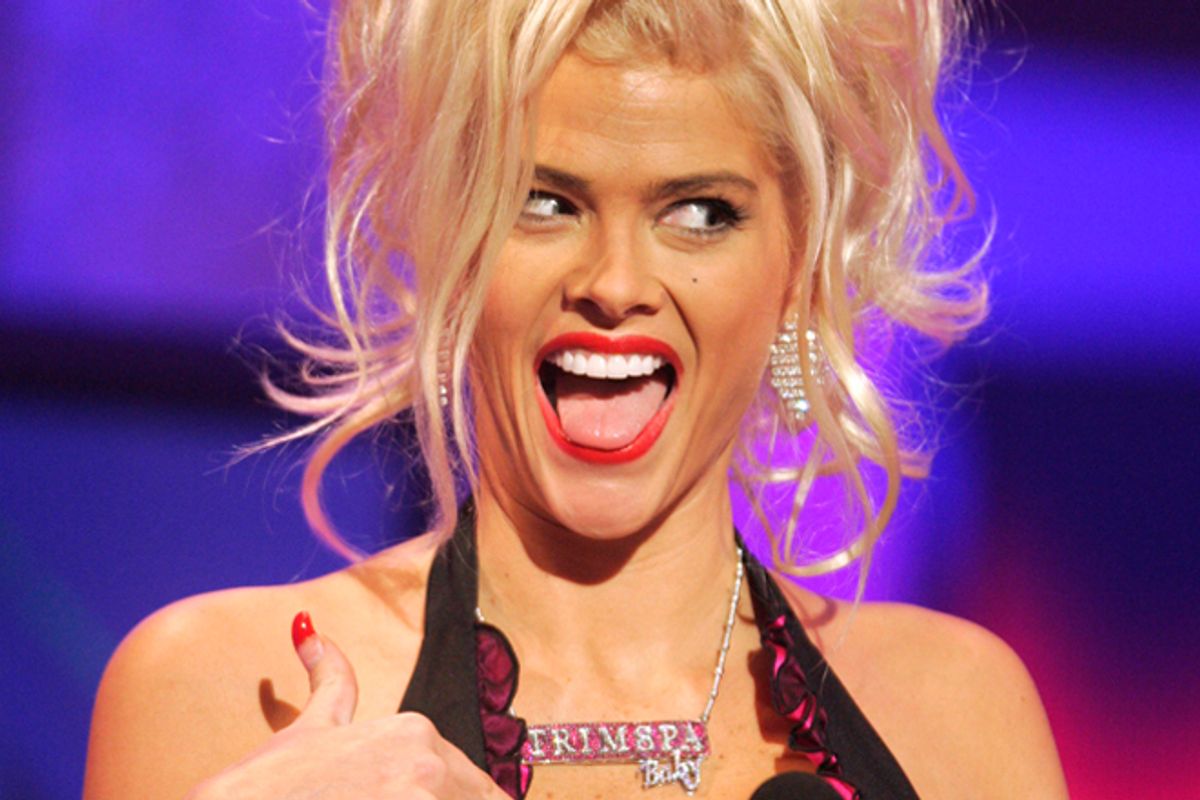

It was a slow death, made all the more worse by the fact that no rescue seemed to be coming—or even felt deserved. And if there was a recovery effort, it was the equivalent of dispatching a single lifeboat to save all aboard the Titanic. In this case, that feeble lifeboat was a flop Kickstarter campaign that only managed to raise a third of its one million dollar goal—just a fragment of the City Opera’s larger shortfall of $7 million! Moreover, no generous-hearted philanthropist swooped in with a big check. In fact, according to the New York Times, the exact opposite occurred. In a September meeting following the opening of Anna Nicole, a well-reviewed opera on the dramatic life of the late human train wreck, the City Opera sat down with David Koch, a longstanding benefactor with exceptionally deep pockets, and talked donations. But when asked “if he could make further gifts to save the company, Mr. Koch demurred, telling [the City Opera] that the Marshall family might be less than pleased” were he to do so. The Marshalls are the heirs of the late oil magnate, J. Howard Marshall II, once a close business partner of Koch’s—though you probably know him better as Anna Nicole Smith’s geriatric lover. The Marshall family never quite warmed to Anna Nicole, however, and it seems this dislike extended to her operatic likeness as well.

“The [City Opera] company could sell out 500-seat theaters and get raves in every paper and still not convince people to give it the kind of support that could ensure its future,” Zachary Woolfe presciently wrote in 2011 in the Observer. “In that case, New York, like Minneapolis, will be a one-opera town.” And so it has become.

Are we to share in the blame for the opera’s decline, then? Maybe, but we’re certainly not the Brutus of the City Opera’s death. If anything we’re more like that other Brutus—the one who delivered the third blow. Caesar was already dying: we just sped up the process.

At the same time, there is something about our culture, especially my generation—us manifold millennials—that is existentially opposed to opera, and uncomfortable with what it says and does with emotions. Certainly the opera can appear haughty, supremely theatrical, perhaps even boring. It is a social space heaving with heavy breasts, shrill sopranos, bellowing altos, and nearly everyone exceedingly well dressed and behaved. But let’s put the opera into perspective—how is Broadway, a terrifically popular pastime, any more affordable, laid back, or inviting? Tickets to the opera can be found for $25 or $30 a head, and many companies offer student discounts and rush tickets. A velvet, formal rope prevails in opera, but it’s one that can easily be crossed—and yet, once on the other side, it can be disorienting and grand.

The real problem is our phobia of unblunted emotion. We seldom admit to being moved, stirred, or crushed by art. Rather, we’re more apt to ridicule something for being overly emotional or mock someone who is. We tightly seal off our feelings—insulated by a thick coat of irony—and avoid bearing big, overt desires and reactions. Opera is our opposite, a sentimental, exaggerated doppelganger. Characters in opera don’t share their feelings so much as disgorge them. Performances teem with huge, unburdened emotions. To an audience ironically allergic to such unalloyed sentiment, opera can seem a most strange, outlandish thing. We’re turning away from opera because we don’t always understand it.

And in the process, we’re turning away from ourselves. Reflecting on the death of his wife in his book, Levels of Life, Julian Barnes painfully observed how his friends and associates avoided talking about her. The opera, by contrast, was an emotional torrent. Going to the opera affirmed his enormous loss and redeemed its intensity. “[Q]uite unexpectedly,” he writes:

I fell into a love of opera. For most of my life it had seemed one of the least comprehensible art forms. I didn’t really understand what was going on…but most of all, I couldn’t make the necessary imaginative leap. Operas felt like deeply implausible and badly constructed plays, with characters yelling in one another’s faces simultaneously… Now it seemed quite natural for people to stand onstage and sing at one another, because song was a more primal means of communication than the spoken word – both higher and deeper… an art in which violent, overwhelming, hysterical and destructive emotion was the norm; an art which seeks, more obviously than any other form, to break your heart. Here was my new social realism.

And then there is Klaus Kinski’s opera-mad Irishman from Herzog’s fanatical 1982 film Fitzcarraldo. So powerful was his love of the opera that it drove him to hauling a steamship over land.

But what about us good, hinged, practical Americans? What would we do for the opera?

Well known as a champion of new and contemporary works—from Anna Nicole toMines of Sulphur—and a stalwart of innovative interpretations (take, for example, Maurice Sendak’s production design for 1981′s The Cunning Little Vixen), the City Opera’s demise was a grievous loss. (It was also the first in the country to incorporate subtitles in its shows, something James Levine once said would happen “over my dead body” at the Met.) For every company and its audiences that are lost, as audiences grow older and smaller, the fewer ambitious and creative opera companies there will be. As audiences grow older and smaller, as the case will be if the young do not join their ranks, would anyone be surprised if opera stuck with what works, the old but reliable cannon? And who’s interested in another revival ofTosca or The Magic Flute? In an arts culture that favors old standards, any loss of diversity and energy is a threat to innovation and new audiences.

The ultimate question, then, is not can we come to lose opera to obscurity or moribundity; it’s can we stand to lose a bit of ourselves, a capacity for enormous expression and resounding feelings. Do we want to live without opera’s ability to overwhelm us in the way that only it can? Should future generations not have that chance?

Maybe we ought to see the opera like the Californian condor or the egret—a species so essential to our lives and nature that it’s worth an expensive, long-running conservation program after years of human indifference. After all, we don’t need the Californian condor to live: We don’t depend on it for food or for clothing, and it’s quite ugly with its bald, fleshy vulture head. We probably need it no more than we need the dodo.

But do I need it? Will I benefit from it being around? Now and in the future? Will you? Will the wider community? I could be talking about the opera or the condor.

Of course, we actually don’t need either. If our world is a sinking ship, then perhaps you’d consider tossing the opera. But that’s all wrong. Like real life, real culture has curves. Opera is one of many species in our culture that’s worth saving, don’t you think?

Perhaps a night at the opera is in order. Then you can make up your mind.

Shares