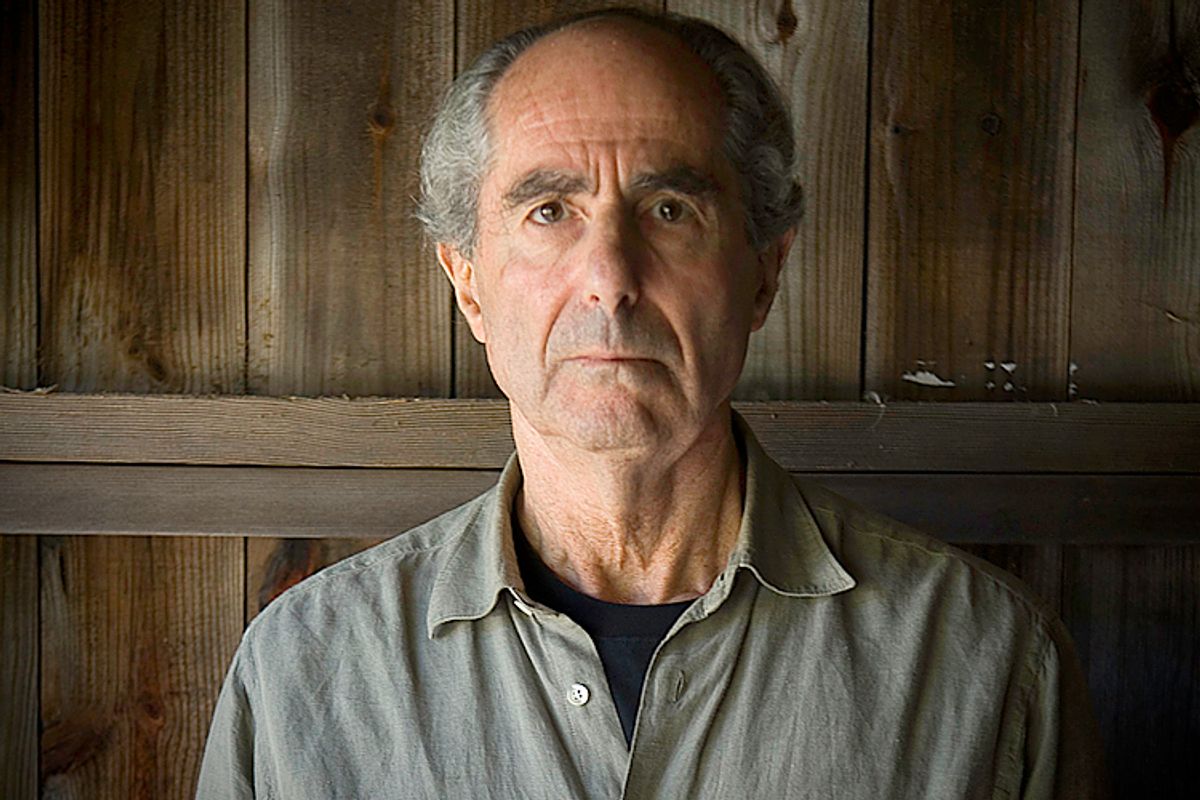

Reflecting on his own feelings at sixty-six, and performing one of his grand sweeps across older men’s writing, the once celebrated literary critic Leslie Fiedler suggested that men’s feelings of impotence, whether metaphorical or literal, can easily trigger devastating phallic narcissistic injuries. My own explorations confirm his, at least when looking at those male writers who have most assiduously focused on old age. One obvious place to start is with the writing of Philip Roth, winner of the Man Booker International Prize for fiction in 2011 and, though a controversial figure – especially with some female readers – often hailed as America’s greatest living novelist. Roth has been expressing his fears about and preoccupations with the effects of time from quite a young age, and his reappearing protagonists mostly age along with their creator.

Indeed, Roth sees himself as speaking on behalf of all his fellow men when he depicts the fears and yearnings that trouble and endanger them as they journey from youth into middle and old age. Thus in his twenty-seventh book, "Everyman," he characteristically sets out once more to tell the story of the ageing male psyche. It is one in which the often painful, inappropriate and rash desires of youth last the whole life through, but become increasingly unrealizable. In Roth’s view, the precise aim or object of such desire changes very little, if at all, as men age. This remains the case even when, as he depicts in abject or hubristic detail in every recent book, the men who continue to be importuned by lust for young women possess no more than a useless ‘spigot of wrinkled flesh’ between their legs. That spigot, emblematic of masculinity, marker of sexual difference, and hence the thing valued above all else, Roth sees as always on men’s minds. Its presence is felt, even when entirely out of action, ‘like the end of a pipe you see sticking out of a field somewhere, a meaningless piece of pipe that spurts and gushes intermittently, spitting forth water to no end, until a day arrives when somebody remembers to give the valve the extra turn that shuts the damn sluice down.’

It is easy, just a little too easy, perhaps, to apply Freud to Roth’s unflinching examination of masculinity and the degradations of male ageing. The young boy’s early ‘castration anxiety’ is once again intensified in Roth’s depictions of the life of the ageing man. Here, it is the anchoring of masculinity in sexual performance, real and fantasized, that underlies the unravelling of men’s ageing identities. If turning to Freud, however, we need to realize that Roth has already got there before us. His novels read, knowingly, like Freudian case studies, and analysts feature prominently in many of his books, beginning with his early runaway success, "Portnoy’s Complaint." In all of them, manhood must be affirmed in ‘sexual conquest’, which somewhere before the end must lead every man into perpetual mourning for the loss of a former imagined phallic prowess: ‘Nothing any longer kindled his curiosity or answered his needs ... nothing except the young women who jogged by him on the boardwalk in the morning. My God he thought, the man I once was! ... The force that was mine! ... Once upon a time I was a full human being.’

In Roth’s writing, a man’s ageing desire is never able for long to eroticize the comforting familiarity of a lifetime companion. However bereft and lonely, it would seem that Roth’s men have little choice but to die as they have lived, as lecherous mavericks. Or rather, since we are discussing Roth’s depictions of phallic bravado, which is inevitably, and as he keeps telling us, fundamentally illusory, Roth is determined to portray men who will die as they would like us to believe they have lived, as sexual predators, if only in fantasy. Nor is Roth, at least in old age, unaware of the price he pays for what he summed up in one interview as ‘the circus of being a man ... [where] the ring leader is the phallus.’ Ever the dutiful scholar, he can also sense something of the artificial or performative nature of the gender enactments he so obsessively describes.

But any real transgression of these conventions, at whatever age, seems beyond Roth’s imaginative purview. Nor can he find anything to admire in the ageing body, male or female. It is this visceral dismay that makes his fictionalized projections of the situation of the elderly so disconcerting. Yet he remains for me an excellent writer to think with, to think through, and to think against, given his pellucid prose and his constant testing of what he sees as the shifting boundaries between art and life, between what can be said, and what remains hidden in life’s journeys.

Moreover, the phallic longings that loom so stubbornly in Roth’s depictions of the lives of men, whatever their age, echo sentiments that have certainly been just as fiercely communicated by other ageing men with the gifts to depict their own dreams, fears and frustrations, not least in the words of the Irish poet W. B. Yeats, who mourned, at sixty-one, that he lived with the soul of a man ‘sick with desire / And fastened to a dying animal.’ Roth borrowed Yeats’ words for the title of a novel in 2001, about the lust of an ageing professor for his young student, around four decades younger than him, though here it is she who is dying, his phallic prowess apparently still intact. Roth’s late writing also resonates with the ‘total disillusion’ and ‘inner ice age’ of Freud’s lunar landscape, when he tells us in "Everyman": ‘Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre.’ I do not actually accept that Roth (or Freud or Yeats, before him) is Everyman, although I think he does capture something about the distinctive fears of many men. Not least because very similar imagery can be found in Roth’s most admired and popular fellow male writers.

Also from the USA, the novelist John Updike was seen by many as Roth’s equal or superior, precisely in his own life-long scrutiny of the inner working of men’s hearts and minds. He was, moreover, quite as concerned as Roth with depicting men’s masturbatory and adulterous fantasies and the ‘power and mobility of the penis’ in men’s prime, soon to be followed by the inevitable frailties and fears men face when ageing. The novel "Toward the End of Time," for instance, was one of Updike’s most ambitious meditations on temporality, mortality and ageing, written in his mid-sixties in order, as he later said, to cope with his own ageing: ‘Sex dies hard; even when the apparatus of sex fails.’ In that novel, the protagonist’s declining physical powers are accompanied by a frantic eroticism, fantasizing lubricious encounters with ever-younger women, even as the effects of prostate cancer leave him, like Roth’s older protagonists, mortified by ‘the pathetic shrunken wreck’ his beloved penis has become.

In the UK, Martin Amis, described by one male reviewer as ‘his generation’s most astute documentarist of ageing,’ delivers the same message. Like Roth and Updike, Amis is early on achingly troubled by the passage of time. Indeed, few people have expressed a more visceral and consistent horror of ageing than Amis, or offended more people in the process. Like Roth too, Amis not only sees masculinity as his special subject, but also writes to encompass what he understands as the universal male predicament. As Joseph Brooker notes, his books survey what happens when ‘the swaggering lad’ all too quickly morphs into ‘the crumpled bloke. ’ The theme of imperiled masculinity is center-stage in the book Amis wrote in his mid-forties, "The Information" (1996), which depicts the trauma of men, just like him at the time, reaching middle age: ‘the whole thing is a crisis’. Here, his main protagonist is a blocked, unsuccessful novelist, weighed down by envy, humiliation and a sense of failure, leaving him chronically depressed, self-destructive and, of course, impotent.

Like Roth also, Amis courts publicity through provocation. Yet once again, in his terror of ageing, and chagrin about mortality, Amis does seem to capture something about fears other men have expressed. In "Experience" (2002), the memoir in which he returns once more to his own crisis on reaching forty, he writes: ‘Youth has finally evaporated, and with it all sense of your own impregnability.’ Of course, however powerful the fantasy, men have never possessed any authentic inviolability any more than women have. Nevertheless, in their youth it is perhaps easier for some of them to imagine themselves invulnerable, or at the very least, easier for them to perform in the world as though this were the case. It is this performance that is likely to falter as men age, hence the devastation. Amis sees no way to recover from the shock. In the opening pages of another of his highly autobiographically resonant recent books, "The Pregnant Widow" (2009), published as its author turned sixty, old age is likened to ‘starring in a horror film.’ He returns to this metaphor in its closing pages, with the narrator, the fifty-six-year-old Keith Nearing, suggesting ‘the horror film, was set to become a snuff movie, but long before that he would be its trailer. He would be an ad for death.’

It is instructive to compare these authors with a recent work by the ageing American gay writer, Edmund White, offering his own witty account of the disruptions and continuities of male ageing. At sixty-six, writing another of his prolific texts, which are almost always at least semi-autobiographical, White evokes his doppelganger protagonist, Jack, a gay writer of identical age, inclinations and attributes as his creator. He describes him slowing down, dozing off, forgetting names, and mourning that ‘his [own] name was now more celebrated than his books, his blurbs more solicited than his stories.’ Yet this Jack, though HIV positive for over twenty years, and fearing that ‘maybe his wits were slowing down in the same way as his vision was dimming and his hearing becoming less acute,’ also reflects that one thing had never changed: ‘His sex ambitions were still the same – to have sex with every man in the world. He would have been a perfect whore, since he found every man do-able.’ Unlike the straight men I have mentioned, however, it seems he can find ways of actually ‘doing’ them, or perhaps, to the sheer terror of men fashioned in the normative mould of Freud, Yeats, Roth, Updike or Amis, being ‘done by them’. Oh no: ‘Just like a woman!’

One thing that no male writer ever seems to suggest, however, is that men lose their longing for sexual encounters as they age, even as their erectile capacities falter. Quite the opposite! This information is in agreement with all the empirical studies of sex in old age, in which older men are twice as likely as women to say that they are still extremely interested in sex. Although, as the British health reporter, Jeremy Laurance, suggests: ‘It is hard to be sure whether the gender imbalance shows the resilience of male interest in sex or the resilience of their propensity to boast about it.’ Either way, disappointment shadows putative phallic vigor.

There is one Swedish study that does attempt to highlight an alternative to the dominant vision of phallic sexuality imperilled by ageing. However, this comes not from any well-known male author, with his fictional or autobiographical representations of ageing masculinity, but from an altogether different source. It is the data collected by a young feminist scholar Linn Sandberg, discussing masculinity, sexuality and embodiment in older men. Sandberg interviewed twenty-two heterosexual men of around seventy and older, and supplemented her interviews with diaries she asked the men to write about their bodily experiences and physical encounters. In both the interviews and diaries the men stressed the significance of intimacy and touch in their experiences with wives or partners. They did not report any waning of sexual desire, but they did often describe a certain shift away from the phallic preoccupations of youth to describe instead far more diverse possibilities for shared physical pleasure and satisfactions.

In Sandberg’s analysis, these old men’s emphasis on their pleasure in the mutuality of touch and intimacy in their relationships – perhaps in bathing or stroking one another – present a clear alternative to ‘phallic sexualities.’ Indeed she sees older men’s affirmation of such pleasures as suggesting a possible way of rethinking masculinity and its pleasures more generally, as something ‘less clearly defined and more fluid’: ‘The case of old men may in fact be illustrative of how to think of male sexual morphologies more broadly. Touch and intimacy could then be understood as a potential for the becoming of masculinity altogether; the non-phallic body is not a characteristic of some men but a potential in all men.’

However, if the rush for Viagra is anything to go by, I fear much more will need to change in the still obdurate symbolic and social hierarchies of gender and ageing before such accounts of the ‘softening’ of older men’s activities can begin to undermine the phallus as the privileged marker of masculinity. Meanwhile, if it is still sexual (con)quest and the comforts that a woman’s (or occasionally another man’s) body can provide that reinforces a man’s sense of self, and then threatens to undermine it as he ages, how different is the situation of the older woman?

Excerpted from "Out of Time: The pleasures and the perils of aging," by Lynne Segal. Copyright © 2013. Verso Books. All rights reserved.

Shares