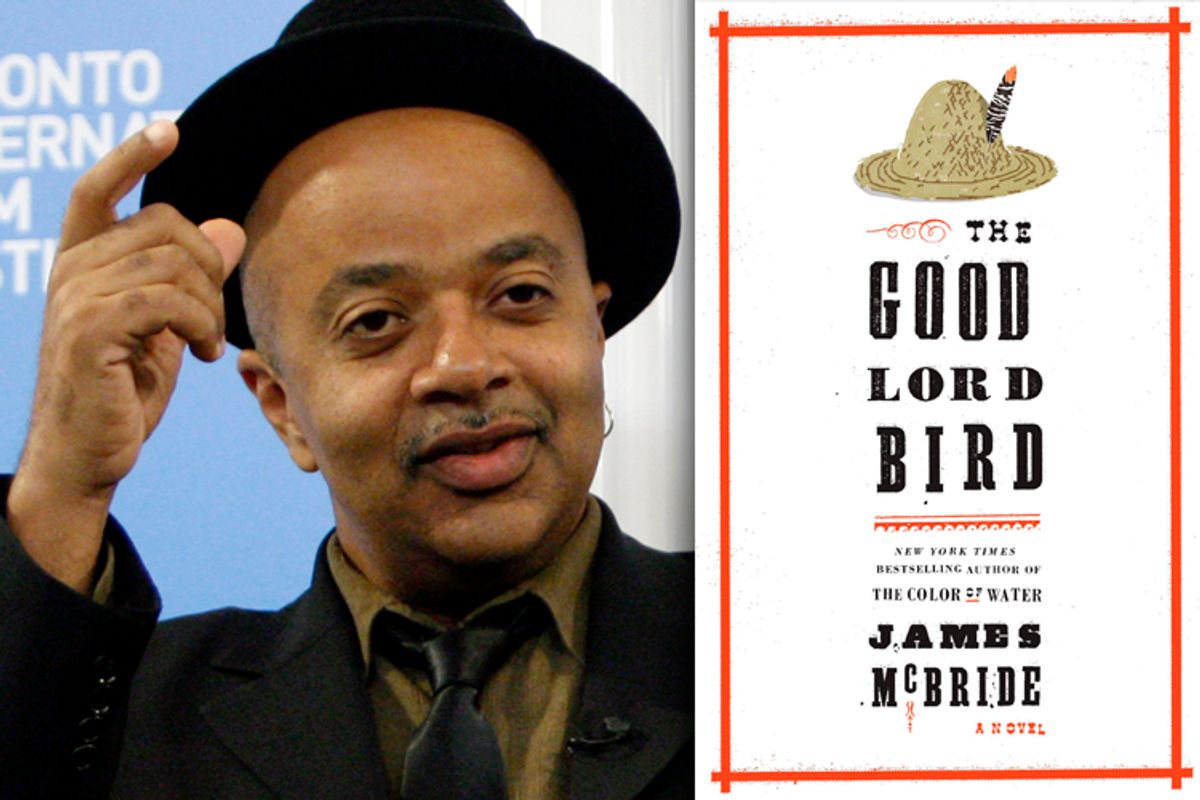

I was surprised to learn that James McBride's "The Good Lord Bird" was the "surprise" winner of the National Book Award for fiction last night. Then again, it's hard to begrudge working journalists a decent angle on the prize during any year in which neither Jonathan Franzen nor Philip Roth has published a book that can be "snubbed" by the panel. Nevertheless, it's interesting to learn that a novel can be characterized as "little-mentioned" even after it's made the cover of the New York Times Book Review.

"The Good Lord Bird" is in fact an ideal NBA winner in the best sense of the term: accessible, smart, ambitious and besotted with Americans' freewheeling use of our language. The novel is so entertaining, it's easy to miss the audacity of its premise: A comic picaresque narrated by a slave, when 1) slavery isn't funny and 2) the roving, carefree life of the typical picaresque hero is pretty much the antithesis of the slave's lot.

McBride makes it work by tossing his child narrator, Henry Shackleford (disguised as a girl throughout most of the novel) into the hands of Bible-thumping abolitionist John Brown, who despite his devotion to winning "her" freedom, is so caught up in his cause that he barely registers the individual identities and desires of the "negro slaves" he aims to rescue. Meanwhile, "Henrietta" complains that the meals in bondage were much better than the ones he gets living rough in the woods with Brown's militia, and spends the early chapters of the book trying to get back to his master.

Beneath its bawdy, vernacular humor and rowdy satire, "The Good Lord Bird" asks painful questions about how much most of us are willing to sacrifice to do what we know is right -- Brown, the novel's only morally rigorous character, is viewed by the other characters, especially Henry, as crazy. And he is crazy, if only because everyone around him, including most of the people he feels called to liberate, have accommodated a social institution that is itself delusional. In the land of the mad, the sane man is an outlaw.

If the novel's comically adventuresome mode needles the high rhetoric and melodrama usually applied to this historical material, the legitimacy of Brown's position undermines the complacency in that strain of American humor that presents itself as "common sense." Some everyday realities simply should not be allowed to stand. These complexities make for a savory novel that does more than just emulate Mark Twain, its most evident influence; they bring the Twainian novel into the 21st century.

The NBA's nonfiction winner, George Packer's "The Unwinding," is similarly remarkable, a collection of profiles reflecting the social and economic history of American over the past 35 years that pointedly refrains from making sweeping polemical arguments about "what's gone wrong." The lives of a factory worker-turned-activist, a disillusioned lawyer, a Silicon Valley venture capitalist and a North Carolina tobacco farmer, among others, are allowed to speak for themselves. In a culture in which everyone is perpetually shrieking their political opinions, it's hard to convey just how refreshing this is. Hell, you might even learn something.

What's the place of the book in a world of digital communication? In these two choices, at least, the National Book Awards suggest that books are where grown-ups go when they want to use all of their minds and hearts.

Shares