As a reader, I always approach the end of a novel, a good novel, with dread and expectation -- dread of a world coming to an end, expectation of submerging myself immediately into a new one. I often read the first page of the next book before I read the last of the one I’m reading. But with some novels, and you know the novels I’m talking about, it’s agony to finish because you know that you will never again read this book for the first time.

Time stops. A long-gone late summer. I’m 22, I’m drunk, I’m in a canoe.

Two old friends of mine, Matt and Alex, and I, were on six-day trip in the Boundary Waters of northeastern Minnesota. The place is my idea of heaven, mosquitoes the size of St. Bernards be damned, and it was up there – on Upper Moose Lake – that I found myself transfixed by another watery place, Virginia Woolf’s rocky coast of Scotland.

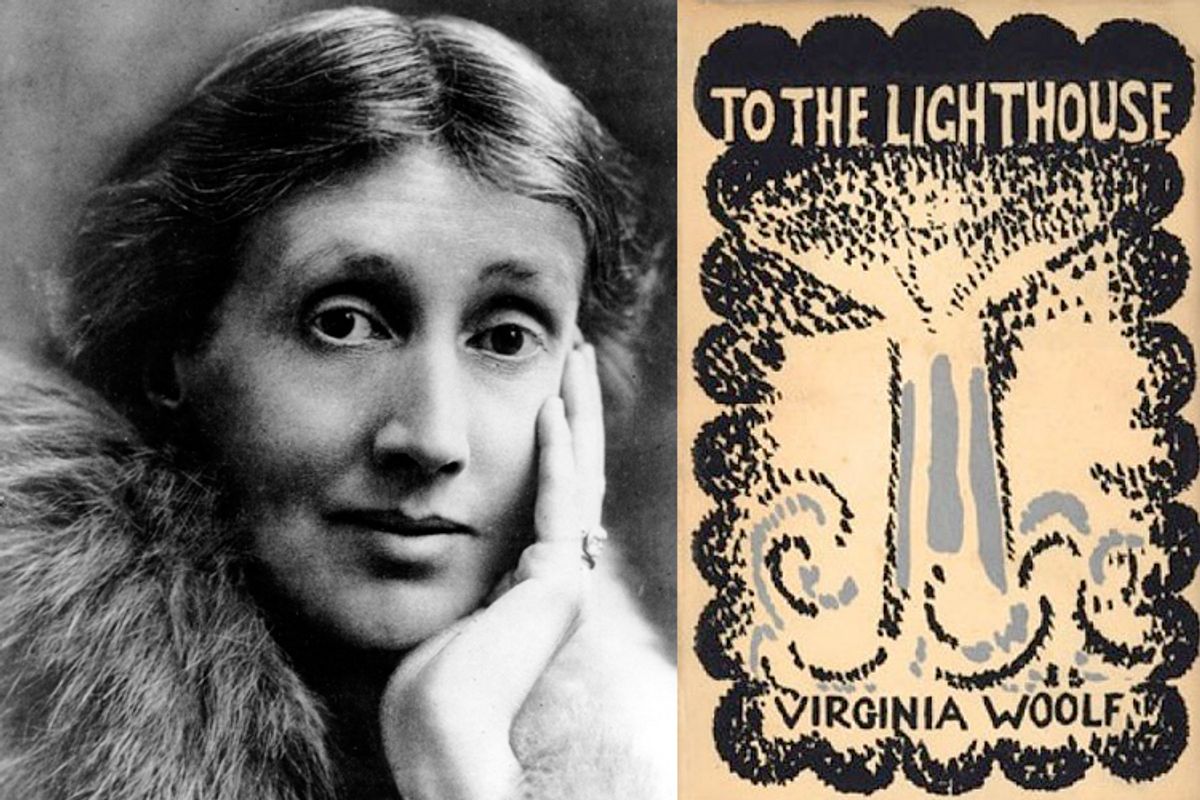

A blazing day, upper 80s, and we were base camping. Our boundary waters trips were always an excuse to base camp; Matt and Alex were in a boat on one side of the lake fishing and drinking, and I was on the other side, in another boat, reading and drinking. (I’m not much of a fisherman, never been able to master holding the rod and turning pages at the same time.) I’d propped myself up on the stern, a life jacket as my pillow. And with both hands I held "To the Lighthouse" up against the sun like some kind of geeky offering.

Lily Briscoe is painting a picture. The picture is not going well and Lily’s frustrated. One wanted fifty pairs of eyes to see with, she reflected. Strange to me now that reading about someone not paint well was so riveting. I remember slowing down, almost to a standstill, counting the pages I had left – the paragraphs – when a dragonfly dive-bombed and drilled into my left eye.

I fell out of the boat. When I broke the surface, I could hear Matt and Alex howling across the water. But all that mattered was Lily: floating, a few feet away, open, face down – drowned. I must have flung the novel during the attack. I let the canoe drift away, rescued the book, and swam it into shore. Then I laid that waterlogged novel on a rock in the sun. And I waited. I sat down beside the book, and I waited, waited for the book to dry so I could turn the pages again without them sticking together.

I’m not an especially patient person, and in my twenties was less so, and yet I didn’t do anything else. I just waited. True, I was a little drunk, and I’ve always been convinced that I concentrate better after a few beers. In the boundary waters we start drinking at 9 a.m. But I know that something else beyond the three or four Leinenkugels had taken hold of me. It took me at least an hour before I could start reading again, and even then the words bled through the wet pages.

I re-read "To the Lighthouse" recently, thinking I might gain insight into a younger self. Who the hell was this guy who could have been so completely entranced by a Sunday painter having trouble with a picture?

I found that it wasn’t the plot. In Part III, the final part of "To the Lighthouse," nothing much happens. We lose Mrs. Ramsay, the beating heart of the book, in Part II. She actually dies, if you remember, in brackets, the saddest afterthought in English fiction:

[Mr Ramsay, stumbling along a passage one dark morning, stretched his arms out, but Mrs Ramsay having died rather suddenly the night before, his arms, though stretched out, remained empty.]

But by the end of the novel, this astonishing, soul-wrenching sentence has since receded. Part III is all about characters who have returned to the scene of what they believe was their greatest happiness. They can’t let go of that past, of their memories of Mrs. Ramsay who, of course, when all is said and done, was a fairly ordinary, if beloved, human being. In death she has become, to her husband, her children, and to her friend, Lily Briscoe, a radiant myth they can’t shake.

Lily tries, through her painting, to replicate the feeling that being back at the Ramsays' summer house gives her. She fails. She can’t translate her visions on canvas. And can’t I relate? How many hours a day do I now spend trying to trap my own elusive visions onto the page? And I am always, always failing. At one point Lily even laments that words – like brush strokes – never seem to be able to do justice to the meaning we want to give them. Words, like paint, will always be static, while the life we work so hard to animate is, one way or another, in motion. To sink the knife in further for anybody who tries to make anything, Woolf, through Lily, spells it out: “There is all the difference in the world between planning airily away from the canvas and actually taking the brush and making the first mark.”

Say it isn’t so, Virginia! I’ve been writing a novel in my head for more months than I can count.

Yet, mercifully, the book doesn’t land on this brutal, inescapable truth. Ultimately, Woolf embraces failure itself as the only possible way forward. In the final pages, Lily accepts the fact that her mediocre paintings will likely end up either rolled up under someone’s bed, in an attic somewhere or, more likely, destroyed. Even so, she’ll paint. She’ll paint. What choice? The only way to honor her visions of the Ramsays is to try and get them down – come what may. The failure to capture the vision is the vision.

And what about my younger self out there on my rock, desperate for a book not to end? Thoughts about the nature of artistic creation couldn’t have had me so mesmerized. I was 22 and pretty much all hormones. Was I hot for Lily Briscoe? For sure. And she was available. She and Charles Tansley never did get together as Mrs. Ramsay had once schemed, so long ago.

I re-read the novel this past summer with solemn admiration, and awe, but for some reason I couldn’t love it, not like I did back then when I was dumb punk kid. What did I know? More than I know now, I think. I was a better reader. I knew how to just exist, without any writerly la-de-da crap, deep inside a book. And I believe what I wanted, even then, alongside running down the beach with lonely Lily Briscoe into the golden Hebridean sunset, was to hold on to what the book tries so doggedly to bring back: irretrievable time.

How else to say it? It was the only wasted youth I’ll ever have. Matt and Alex and I talk, we still talk, about going back to Upper Moose. We haven’t made it back there together in an almost a quarter century now. No tragedy, just something that’s never happened. Still, can’t I grieve for what’s been lost, however small it seems? Once, in late summer, I sat drunk on a rock and waited for a book to dry. Two old friends, their quiet murmurs, reach me across the water.

Shares