A click. Rzzzzzzzz! Line spools off the reel at breakneck speed.

A lusty bellow, ‘dolpheen!’ Seconds later, another downrigger pops, and more line starts paying out. Two dolphinfish hooked, and where there are two, there are probably more. (These are tuna-like fish, not the beloved mammal.) Eyes gleaming, Big Joe notes the location of the sargassum patch and leaves the helm to take one of the rods, while his friend Mac takes the other. This is commercial fishing, not sport, so the tackle is heavy and no time is wasted playing the fish. Soon a pair of twenty-pounders are aboard and the boat is circling back for more. Gorgeous fish while alive, a riot of gold, green, and blue, dolphin quickly lose their colour when caught. Occasionally Joe feels a twinge of regret at killing these lovely creatures. But not today. Today he is fully in the moment, locked in on his prey, and whoops with delight as they haul in another pair.

More ballyhoo on the downriggers, more dolphin on the line. ‘Gaw-damn! Reel’s gettin’ hotter ’n a [something unprintable].’ All told they bring in a couple of dozen, enough for a good profit. Satisfied with the day’s catch, Joe puts his twenty-three-foot Sea Ox on a heading for home. A spare, utilitarian boat with twin Mercury outboards and an open cockpit design, the Sea Ox is not for the faint of heart. Not, at least, if you plan to fish forty miles offshore, well into the Gulf Stream, with only a compass and your eyes for navigation. Getting home means hitting a target, an inlet, perhaps a mile across, after hours of meandering through a six-mile-an-hour cross-current. If you do find the inlet, you must thread the boat through some of the most treacherous waters on the seaboard, using throttle and wheel to avoid getting broadsided by a wave or pitch-poling the boat—nose-diving into a trough, flipping end over end. In which case your remains could well become a fine meal for the crabs.

Yet Big Joe Fletcher is in his element. On the long ride home, he is silent, unreflecting, attention fully engaged with the sea, the sky, the boat. Were you to ask him what he feels, he would tell you ‘nothing’. He is absorbed in the moment. Passing through the inlet brings a bit of tension, but this quickly fades once they reach the comparatively sheltered waters of the sound. Back at the dock the men share a couple of cans of beer while cleaning the fish, exchanging jokes and friendly gibes with other boaters and passers-by. Joe gives some of the steaks to Mac, keeps some for himself, while the remainder will end up as ‘mahi mahi’ on the plates of lucky tourists in local restaurants. (‘Dolphin’, the local name, doesn’t go over so well with some diners.)

In the evening, Big Joe and his wife Pam expect to stroll back down to the docks to join the sunset crowd. But some friends drop by and they pass the evening on their front porch, laughter punctuating a chorus of crickets, frogs, and cicadas. An hour later, a couple more wanderers join the fun. Out come a couple of guitars, and the small band of ruffians adds its own music to the nighttime choir.

Things have not always been easy for Joe. He’s had his share of romantic troubles and financial difficulties. But at this stage of his life, things are good. The fishing is solid, and between that and the odd carpentry job, the bills get paid. He doesn’t need much cash—the house he built himself, and just about any maintenance work on that, the boat, or his truck he can do himself. Many other things can be had by trading with his neighbors.

Joe himself is a big man, in just about every way. A tall, red-bearded man carrying a few more pounds than strictly necessary, and possessed of a booming voice, he carries his bulk with confidence and ease. He does not anger easily, nor is he prone to fret; problems are a part of life, and there’s no point worrying. He is big in spirit too: sharp-witted, quick to laugh, exuberant and vital, not given to guile or indirection, he is fully his own man. All the more so since leaving his job at a mainland boatyard. Spending his days at the beck and call of another man never sat well with him, made him feel unnaturally small. Better to be free than a wage slave, even if it means doing without a few things. Big Joe Fletcher is, and feels, free.

You probably won’t need much convincing that Big Joe is a happy man. But on what basis would you make this judgement? The description doesn’t include Joe’s opinion on the matter, and you could well imagine that he doesn’t really have one.

In Joe’s case, as in real life, we judge how happy someone is not by opinion polling but by observing the person: Do they have a spring in their step? Do they seem tense, tightly wound? Comfortable in their skin? Do they just seem ‘off ’? Do they laugh easily? Get angry at little things? Burst into tears over minor frustrations?

What we are doing, I think, is trying to assess the person’s general emotional condition. The term ‘emotional’ can mislead, since it suggests a narrow focus on feelings like joy or sadness, fear or anger. But being tense isn’t really an emotion at all. And what

your posture or stride reveals about your ‘emotional condition’ is something other than an emotion. It’s something deeper than that.

We sometimes try to get around the limits of emotion words by speaking of the psyche or soul. Think ‘she’s in good spirits’, or Bob Marley’s plea for a lover to ‘satisfy my soul.’ But I think these sorts of cases involve broadly emotional matters nonetheless, so I will stick with ‘emotional condition.’

If this suggestion is right, then much of our everyday thinking about happiness identifies it with a person’s emotional condition. Roughly: to be happy is to have a favorable emotional condition. Let’s call this sort of view an emotional state theory of happiness.

So we have a definition of happiness. Is it a good one? Well, we probably can’t point to any single definition and say that’s the correct one. But I would suggest that it’s a pretty useful way to think about happiness. It makes sense of the weight people place on happiness, as when a parent says he wants his children to grow up to be ‘happy and healthy.’ While I will sketch some reasons for preferring this view to the main alternatives, I will not delve deeply into the debate here. Suffice it to say that, while many people find an emotional state account of happiness attractive, I am not describing a consensus view here. The alternatives remain popular as well.

The three faces of happiness

Let’s explore this view of happiness in further detail. What exactly does happiness involve? When people think about happiness in emotional terms, they tend to picture a specific emotion: feeling happy. So powerful is this association that happiness frequently gets reduced to nothing more than cheery feelings or ‘smiley-face’ feelings. This is a radically impoverished understanding of happiness: there’s much more to being happy than just feeling happy.

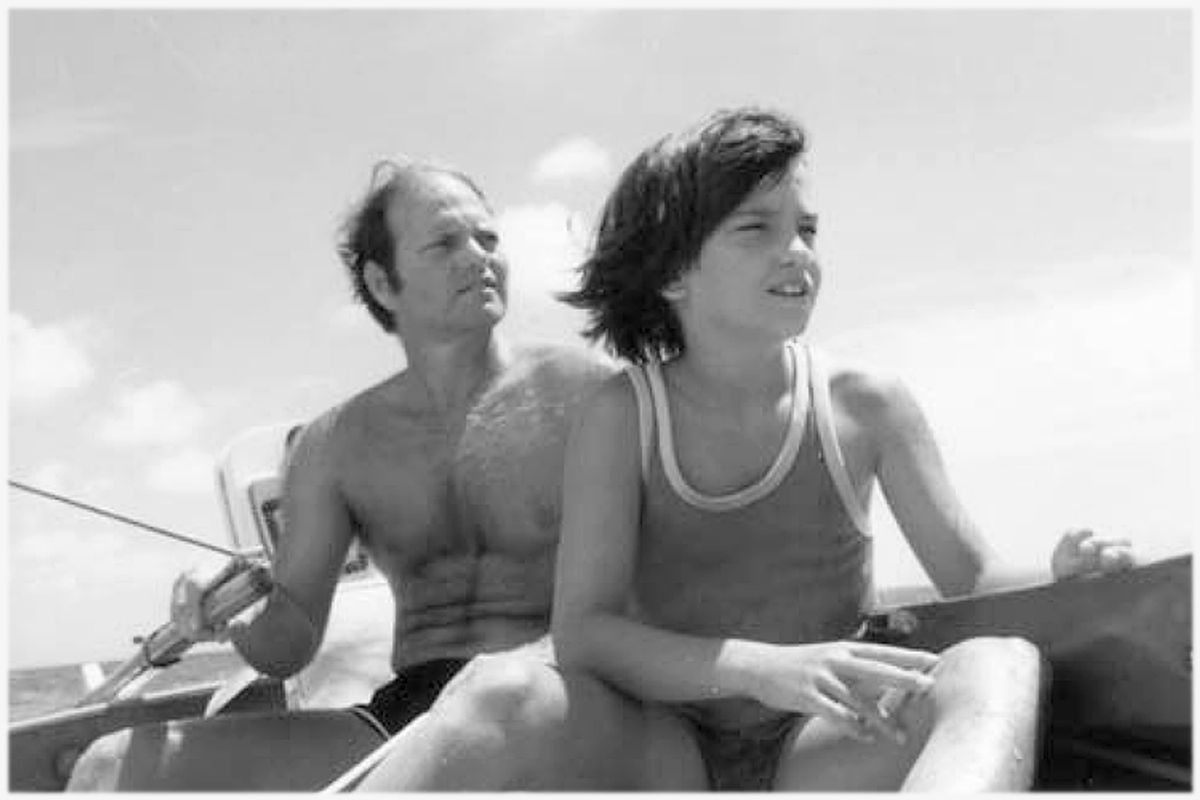

Think about those periods in your life when you were happiest. Not so much that day when you were elated over a special event, like the birth of a child. Rather, those times of relatively sustained happiness. Not everyone experiences such periods, but if you have, I suspect they looked something like our picture of Big Joe Fletcher, or the photograph of my father and me in [the picture above]: good stretches of time wholly absorbed in something you love doing, feeling fully yourself and in your element. Energized, alive, and yet also, deeply settled and at peace—no doubts, no fretting, no hesitation. And yes, feelings of joy here and there, perhaps a good dose of laughter. But those feelings are not the most important part of the story.

We can usefully break happiness down into three broad dimensions. Arguably, each dimension corresponds to a different function emotional states play in our lives. But in this book I will skip the argument and simply present the view.

We can think of happiness as a kind of emotional evaluation of your life. Some parts of this evaluation are more fundamental than others. At the most basic level will be responses concerning your safety and security: letting your defences down, making yourself fully at home in your life, as opposed to taking up a defensive stance. I will call this a state of attunement with your life. Next come responses relating to your engagement with your situation: is it worth investing much effort in your activities, or would it be wiser to withdraw or disengage from them? Finally, some emotional states serve as endorsements, signifying that your life is positively good. People often make the mistake of thinking all emotional states are like that.

Excerpted from "Happiness: A very short introduction" by Dan Haybron. Copyright © 2013, Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.

Shares