To the fog of war, add the fog of breaking news, that period in the aftermath of a disaster when mistake, rumor and other forms of misinformation cloud our understanding of what’s happened. Accounts of John F. Kennedy’s assassination on the 50th anniversary of that event have reminded us that this form of confusion predated the Internet and cable news. But today the news cycle has sped up, ravenously seeking new fodder in a matter of days rather than weeks. By the time more responsible investigators have nailed down the facts, the public is often no longer paying attention.

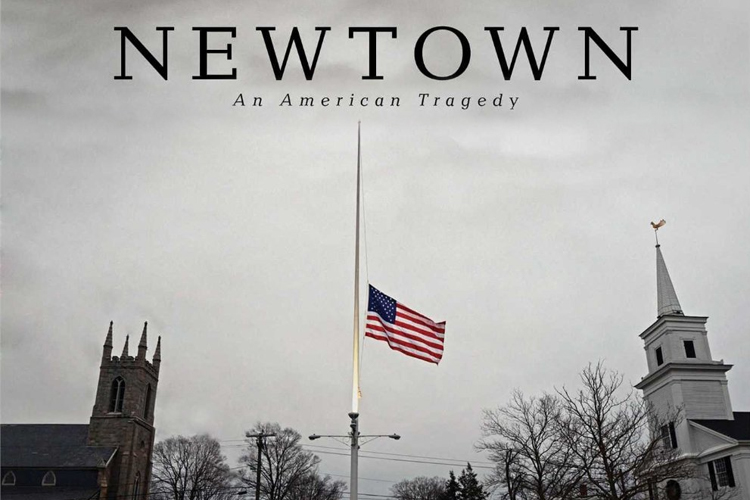

For this reason, there’s more call than ever for books like Matthew Lysiak’s “Newtown: An American Tragedy.” Lysiak, a reporter for the New York Daily News, covered the story of the mass shooting that took place at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Conn., a year ago on Saturday. At the time, the press misidentified the murderer, 20-year-old Adam Lanza, as his older brother, Ryan. (Adam was carrying Ryan’s ID when he shot himself at the end of his rampage.) There were reports that Lanza’s mother, Nancy, worked at the school and was killed during the shooting. (Her son shot her three times in the head that morning as she lay in bed, then left the house for Sandy Hook.) And there was talk of a second shooter — actually a parent, apprehended then cleared by law enforcement officials when they arrived at the scene. Depending on when you checked out of the coverage, you might be harboring all sorts of erroneous ideas about the tragedy.

“Newtown” is a just-the-facts narrative, and Lysiak is no prose stylist; he has an unfortunate propensity for clichés and dangling participles. But this book shows a deeper grasp of how to assemble those facts into a meaningful picture of events, and it is tremendously moving in the simplicity of its presentation. Lysiak balances perfectly the ordinarily wondrous lives of the 20 children and six women who were murdered against their killer’s depravity. Lysiak is a master of texture, at selecting precise, individualizing details: the first-grader who asked her mother for extra tissue paper to wrap the gingerbread house she planned to make at school that day, the way Sandy Hook principal Dawn Hochsprung sometimes snuck her paperwork with her into the stands when attending school athletic events, the “plush blue shark” slipped into one small coffin.

Lysiak’s account of the shooting itself, which lasted about five minutes, and the events leading up to and following it are tersely horrific. The slaughter of so many innocents makes Sandy Hook one of the darkest nightmares in the ever-growing list of America’s lone-gunman sprees, but it does have a heartening counterpoint in the selfless courage of the women who died that December morning trying to protect their charges. Hochsprung gave her life to warn her colleagues of the danger, first-grade teacher Victoria Soto stepped between Lanza and her students, and when teacher’s aide Anne Marie Murphy could not hide 6-year-old Dylan Hockley from the murderer, she wrapped her body around his in an attempt to shield him.

Within a day or two of this atrocity, everyone was arguing about its cause and significance, and these debates become part of Lysiak’s narrative as well, though not to the point of overwhelming the story of Newtown and its citizens. The loudest rhetorical clashes occurred between gun control advocates and Second Amendment absolutists like the firearms-industry-funded NRA, but other debates raged as well: over the import of Lanza’s diagnosis of Asperger’s syndrome and whether reporting this was prejudicial to people with autism, as well as Lanza’s obsession with video games. Interest groups fearing stigma or regulatory crackdowns sought to deflect fault elsewhere: The gun nuts blamed the video games and a lack of adequate mental health care, the gamers blamed Lanza’s parents, and advocates for people with autism blamed the gun industry. If there was a paucity of information, there was certainly no shortage of opinion and argument.

For the most part, Lysiak avoids interpretation of his own. Through a judicious use of expert quotes he conveys that people with autism are not mentally ill and are no more prone to violence than the neurotypical. No causal relationship between video games and violent behavior has been shown. Finally, all of the guns Lanza owned were acquired legally, by his mother, although it seems obvious that whatever reason one might have to own a weapon capable of firing scores of rounds and mowing down 26 human beings in five minutes is probably a really, really bad reason.

Nancy Lanza was the one person in a position to see how far off the rails Adam had gone. She was a tireless advocate and caregiver for her son, who had multiple neurological conditions that made it difficult for him to lead a normal life, and who had become totally isolated. He had no friends and seldom left his room (although a report released last month suggested that he might have visited a local theater to play Dance Dance Revolution). He could not bear to be touched, eventually communicating with her primarily by email, and was distressed at the slightest variation in his environment and routine. In the past, a major tailspin had been triggered when he started high school and was expected to change classrooms several times per day. His mother eventually pulled him out of school and educated him at home until he got his GED, and the Lanzas, it should be noted, were well-off enough to get him proper care.

For Nancy — described by a friend as a “live free or die” New Hampshire native who “came from a culture of guns” — target practice was a wholesome family activity and one of the few ways she felt able to bond with her son. Yet Lysiak also establishes that in 2012 Nancy Lanza was both very concerned about Adam’s mental state and had more or less given up on drawing him out of his shell, although she did hope that a planned move out of state might change that. Furthermore, Nancy was worried enough to venture into the forbidden sanctum of her son’s room, where she discovered many disturbing drawings, “gruesome depictions of death, images of mutilated corpses,” including a “grassy field lined with the corpses of young children.” Was she also aware of the “massive spreadsheet, seven feet long and four feet wide,” ranking “the top five hundred mass murderers in world history”? That would seem like a hard thing either to miss or to shrug off.

According to a friend in whom Nancy Lanza confided after finding the pictures, she hesitated to confront her son because “she feared he might further shut her out” and “he would be lost forever.” Adam Lanza was also, by that point, heavily armed, and if his mother worried that any disturbance might provoke a violent reaction, she was probably right. Yet a resistance to seeking help — or, perhaps, a contentious temperament that caused her to find fault with much of the help offered — had left this self-reliant Yankee with the perception that she had few options.

The contrast here with the abundantly interconnected community of Sandy Hook is obvious, although Lysiak never underlines that point. Other people, for all their meddling and aggravation, can be, among other things, an excellent source of reality checks. One of the pieces of evidence found in the Lanza house after the shooting was a bank draft that Nancy Lanza had written for Adam’s forthcoming Christmas present — yet another gun.