This year was a far more annoying year on the Internet than was 2012. For all that major, pre-planned events like the Olympics or the presidential election gave rise to misbehavior online in 2012, at least everyone was in possession of a unitary set of facts. 2013 was a year in which everyone who plugged his or her brain into the Internet each morning burrowed yet deeper into their own discrete corners; occasions for shared experience, large or small, were jarring for their mere existence as well as for their character. It took the worst to draw Internet users together.

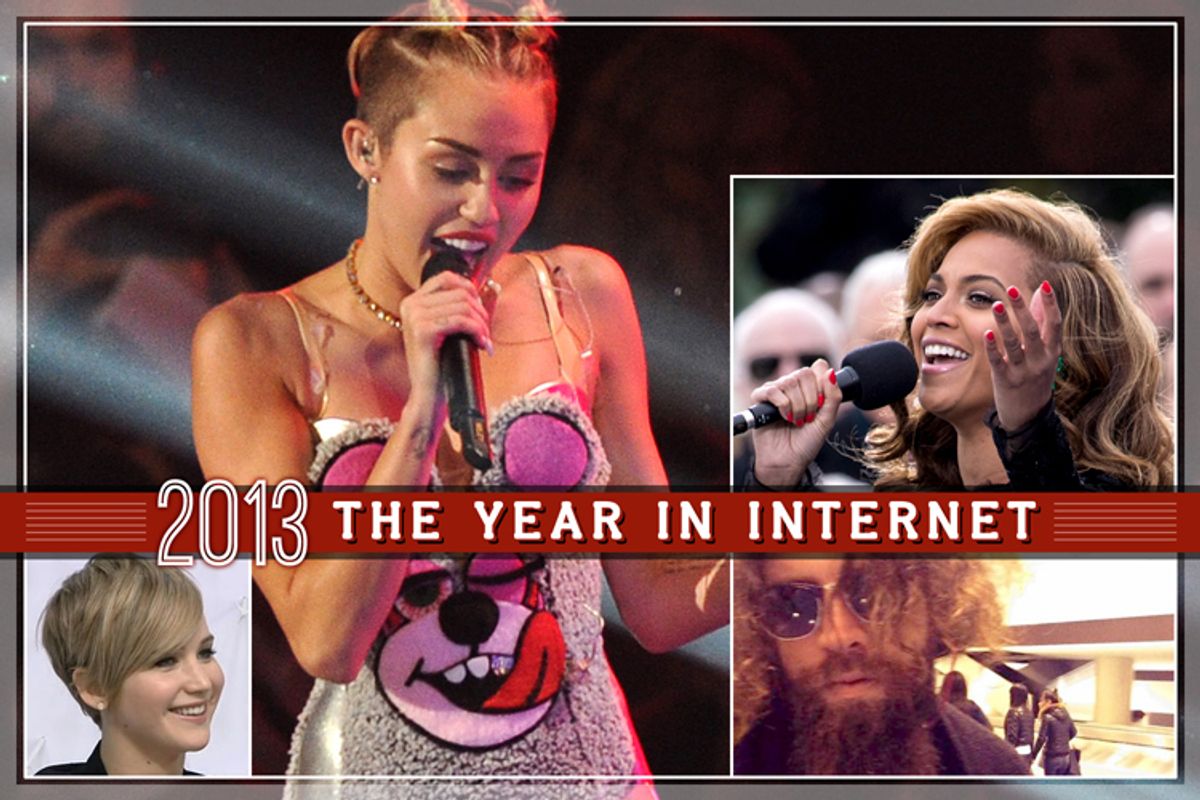

Take, for instance, January’s big news event: the inauguration of President Barack Obama for his second term. The address, entirely anodyne but for a glancing mention of “Stonewall” signaling further “evolution” on gay rights on the president’s part, would not have had a long online shelf-life were it not for Beyoncé’s evident lip-synching of the national anthem. Beyoncé is presumed, online, to be beyond debate: She organizes her fans through her “BeyHive” site, and is an argument-ender in message-board conversations about the greatest current pop star. Beyoncé’s answer to all the critiques was to perform the national anthem a cappella at a press conference streaming online and to declare brazenly “Any questions?” after hitting the high note on the “free.”

This was the way of things in 2013 online: The few things that the culture industry could presume everyone would see were neither good nor bad, but framed perpetually as “epic” or “fail.” Beyoncé’s lip-synching was the utmost betrayal. Her slaying the national anthem shortly after was an utter win, though it answered nothing; no one had been questioning whether or not she could sing. Anyone who’d critiqued her in the first place was just a “hater.”

For all the talk of “think-pieces” this year, the thoughts catalogued were remarkably short-form. Millennials were going to save us all, unless they were, on the basis of a single piece of evidence, unable to cope with life to a degree verging on mental illness. “Breaking Bad” was going to have the best series finale ever, until it sort of didn’t, but never mind, Walter White is still a bad-ass. Going any further or any more particular consigned one to failure: the super-successful website Upworthy removed Jennifer Lawrence’s name from a headline because she might not be recognizable enough on name alone. Miley Cyrus was a human hashtag, one whose racially exploitative valences were closely explored in posts that were far harder to digest than ones merely remarking that she was being gross and weird! To distinguish oneself from the hum of a now-chokingly thick recap scene every Monday morning, one would have to respond to a complex and eerie "Girls" episode by saying that Lena Dunham wasn't hot enough to have sex with her onscreen partner. Transparently false information about the bombings of the Boston Marathon and the subsequent investigation was quickly transmitted simply by dint of its extremity. It felt as though individuals and news outlets were struggling to get the attention of a more-diffuse-than-ever Internet, and once they had it, unsure of exactly what to do.

The less reported content on the website BuzzFeed, which has room for both international scoops and GIF-heavy posts on 21 Signs You’re From Connecticut (ha ha, I am!), was presumed to be some sort of malign force, but its success was symptom, not cause; everyone’s Internet was so particular and so “curated” that a Weekly Reader-style digest of what was big online couldn’t help but succeed. Its lack of editorial voice was its greatest strength -- one could read into BuzzFeed whatever one wanted. It fit everyone’s Internet (something fundamentally misunderstood by those who expected the new book section to feature negative book reviews when it did not feature book reviews, full-stop). As of December 2013, the site hadn’t run out of states you know you’re from, colleges you know you went to or hobbies you know you have.

But a sort of reality hunger, to borrow a phrase, seemed to infest the Internet; the Web had already effectively cannibalized nightly TV viewing, and so any sort of experience that could be shared communally was, for a moment, exciting. Ten years ago, there is no way that “The Sound of Music” would have gotten the ratings it did; its success was self-sustaining on Twitter, as no user wanted to miss out on the opportunity to tweet about something all his or her followers would actually understand, even if the tweets were witless snark or mindless smarm, either way. The Elan Gale incident, framed by Gale as a true story of his shaming a fellow airline passenger, was passed around and presented as incontrovertible truth in spite of its obvious deviations from how air travel works. The Super Bowl and the Oscars resembled open-mic night at a comedy club on Twitter, with satirical site The Onion going too far in mocking child actress Quvenzhané Wallis with an ugly term. But it was only a millimeter farther than the evening's general tone; Oscar host Seth MacFarlane, with his nasty and crude opening number about nominated actresses’ “boobs,” had explicitly been chosen to connect with the Internet generation.

And anything one degree removed from whatever topic was up for discussion had the frisson of outright rebellion. The concept of “longreads,” fetishizing anything that ran to more than, say, four pages in a magazine, regardless of whether or not it was good, gained currency; metric tons of journalism that was not, strictly speaking, interesting, ran on the New York Times website retrofitted with cool visual effects so as to get across the idea that, unlike the rest of the Web, this was Important. The cover of The New Yorker became a place to witlessly observe that news was happening and it’d be a shame to miss out on likes from people who don’t actually read the magazine.

My specific Internet this year was terrific. The “Justice for Bionic” movement (whereby pop music fans sought to get back at Perez Hilton by buying a two-year-old Christina Aguilera album) or the fun I had being weird on Twitter were unlikely to make a huge dent on the viral Web. But the occasions on which The Internet intruded upon my refreshing all my feeds was consistently frustrating. I had mused earlier in the year about whether or not there was a future for the Internet beyond the hate-read, and I’ve concluded it can only be undertaken by the individual.

The most successful websites are too massive, and too interested in spinning out their own success, to change their ways -- and they also don’t think they’re soliciting hate-reads. The most successful Web posts simply put forward half of an idea (Rob Ford is weird!, #twerking) and allow you to impute love or hate as you will. Within 14 hours of the release of Beyoncé's fifth album, there was boundless enthusiasm as well as at least one self-consciously provocative piece responding to the album with bons mots like "BOO FUCKING HOO," "Make it stop," and "Meh." There was no idea here, but someone needed to plant a flag; some writer had to go respond to the one thing we all knew about, even if the response was just unreflective annoyance. Another piece "reflecting" on the hype over the singer compared her fans to Nazis. It was the other side of the coin of a BuzzFeed post praising the singer; 21 Ways You Know You Hate Beyoncé.

Everyone’s Internet is still individual, because an argument provocatively argued, intended to inspire a response more fervent than "agree" or "disagree," inspires nothing more than sustained reading. Sustained reading is time spent not clicking any other links. It got less important in 2013 and could well disappear next year. Maybe it’s time to spend more time logged out; I know a website that could recommend a praiseworthy book.

Shares