The last sound the audience hears before the lights go down to kick off Act 1 of the Joe Iconis musical "The Black Suits" are the strains of the Hold Steady's "Stuck Between Stations," the opening track off the group's third album, "Boys and Girls in America." It might, initially, seem a strange choice for a small-scale musical, the sort that's playing smaller houses while it works out exactly what it wants to be when it grows up. Musical theater, after all, isn't a place for the rough-and-tumble, if literary, lyrics of the Hold Steady, and it's certainly not a place for the sorts of throwback power chords the group specializes in. When rock music makes its way to Broadway, it's usually been safely anesthetized and pulled back. It's one of the reasons the American theater increasingly seems like a niche scene, only able to engage with popular musical forms as a sort of novelty act.

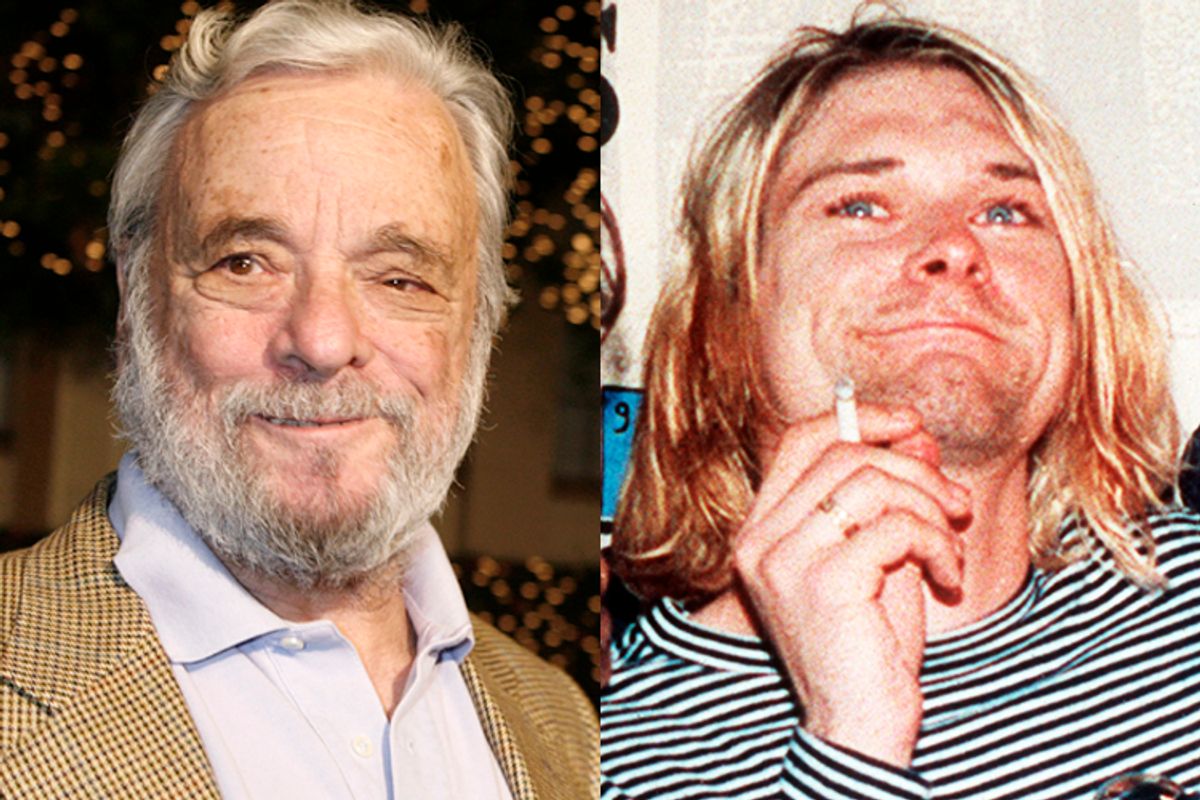

Yet in recent years, stages have started to ring with the sound of musicals constructed less out of a need to have every word perfectly understood and articulated and more with the wish to convey a feeling of raw longing. Though none of these shows have been the sorts of mega-hits that win massive amounts of Tonys and run for over a decade, they feel remarkably fresh, not least of which is because they seem as if they could have arisen out of some concept album recorded by an unlikely indie rock super-group. The composers of those shows openly state in interviews and blog posts that it seems important for anyone writing a musical today to understand modern musical forms — if not to have played in a band themselves. In everything from style to proclamations about the dangers of fame, they can seem more driven by Kurt Cobain than Stephen Sondheim (though all genuflect in Sondheim's direction when needed). Musical theater, for lack of a better term, is having its indie-rock moment.

Popular music and the theater have had a troubled relationship since the musical theater was popular music for much of the first half of the 20th century. In a blog post, composer Dave Malloy (about whom more in a bit) argues that the split came not because rock music was somehow incompatible with the Broadway stage but that musicals are generally about communication of lyrics. When watching a musical, the audience wants to understand what the singer is singing, the better to follow the plot of the show. A rock group, however, only really requires the audience to understand the lyrics as an added bonus to the experience of hearing the song. Great lyrics are a value-add; the real success comes when the audience is emotionally stirred.

I'm already reducing Malloy's rather complex argument down a bit too much, but there's something to it. Far too often, the theatrical idea of rock music is either trapped in the past ("Grease") or feels that simply popping electric guitars on top of the symphonic score will be enough to make everything poppier (essentially anything from early Andrew Lloyd Webber). There's nothing necessarily wrong with this, but it goes a long way toward understanding why musicals chase themselves further and further into niches. And it's not as if musicals have failed only rock. Everything from hip-hop to country to folk inevitably has whatever edge it boasts sanded down when it ends up on Broadway, a million jukebox musicals for a million bands of decades ago turned into exercises in nostalgia and lyrical precision, rather than anything real or raw or powerful. There are figures who escape these shackles — Lin-Manuel Miranda, for example — but for the most part, musicals make popular music seem anodyne.

This means the dominant mood of musicals for the past several decades has been either pastiche or ironic meta-commentary on the genre itself (or, worst of all, ironic pastiche). Both can be fun in small doses (as "Avenue Q" and "The Book Of Mormon" prove), but when overindulged in, they tend to turn the stomach sour. The former keeps regurgitating itself; the latter holds the very form it's commenting on in a kind of understood contempt. To be sure, Sondheim kept on doing what he does into the '90s, and there have been bright spots of composers who've followed in his semi-classical footsteps (most notably Adam Guettel of "The Light in the Piazza" and Jeanine Tesori of "Caroline or Change"). But most musicals put onstage nowadays feel like they're produced almost solely for tourist audiences who want the rough edges sanded off or the sorts of people who will chuckle knowingly at a long string of sus-chords. The indie-rock musical, though, sneers at such things, whether directly or indirectly. It takes aim at puncturing such pretensions with raucous sincerity.

It's hard to trace, precisely, the lineage that has led to this recent brand of indie-rock musicals, but it probably starts all the way back at "Hair" (which Malloy speaks approvingly of in the post linked above). Of all of the "rock musicals" to have made their way to Broadway since "Hair" landed, it's the only one to have slipped into the culture as a whole and outside of the musical niche, and no wonder: It was very much a show of its moment, constructed out of bits and pieces of the late '60s, both in terms of story and music. From there, it's a short trip past the British mega-musicals that used something very like operatic prog-rock as a basis (outside of the weird funk mélange of "Jesus Christ Superstar," the best show of that particular movement and a touchstone of the indie-rock musical) and we land at "Rent."

"Rent" is a fitfully good show — if one that seems impossibly stuck in the time in which it was written and incapable of reaching past it — but its score got too much credit for embracing popular music forms because it had the aforementioned electric guitars. At all turns, it sounds like what a theater geek's idea of what popular music might be, a mostly safe run through some faux-edgy musical styles meant to complement the show's faux-edgy characters. It's no surprise that the show's most enduring song is a straightforward piano ballad that wouldn't have felt out of place in nearly any other musical of the time period.

No, ignore "Rent" and take a look at a different show to find the most recent roots of the indie-rock musical: Duncan Sheik's "Spring Awakening." Sheik, of course, was a popular musician before he found his way to Broadway, and his "Spring Awakening" combines many of the elements that would become touchstones of the indie-rock musical. It's populated with songs that steal liberally from punk and alt-rock influences (check), its story is about a bunch of kids experiencing overwhelming emotions (check), it worries less about perfectly conveyed lyrics than it does about conveying the emotional meaning of what's going on via the overall soundscape (check), and it's sincere almost to a fault (bingo). Topping everything off is that it takes as its source material — an old German play — something that wouldn't seem a good fit for a rock musical, an occasional dalliance of the indie-rock musical. "Spring Awakening" was a huge hit, winning multiple Tonys and running for several years, as well as spawning several successful careers. Sheik, however, has yet to follow it up with anything as immediate or powerful, even if the show's success seems to have thrown open the doors for a lot of shows that have taken the format of "Awakening" and improved upon it.

Another important figure in this scene is Michael Friedman, whose 2010 show "Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson" — which fairly bombed when it made its way to Broadway — seems to have taken on a larger life after death. In many ways, Andrew Jackson is the perfect embodiment of what the indie-rock musical has become. It takes everything "Awakening" did and sands away some of the rough edges, then layers in just enough jokes that it seems like ironic meta-commentary before going for the jugular. The show's rock score is propulsive, and it trades freely off the iconography of the American rock star to make its point about the poisonousness of personality cults in political circles. When it circles back around by the end of Act 2 to reveal its true subject matter — the genocide of the American Indian — the show has sneakily worn down the defenses to the point where it's able to speak with a bracing earnestness. Friedman has yet to follow up "Jackson" (though the show's book writer and director Alex Timbers has branched out to become one of Broadway's most promising young directors), but the show's torch has been picked up by Iconis and Malloy.

Of the two, Iconis is more traditionally tuneful, even if he's been the least successful of this wave of composers in terms of shows. His songs draw equally from the world of indie rock and the world of Tin Pan Alley, which gives even his best tunes the sense of having one foot in both worlds, but his lyrics are so clever and his melodies so tuneful that no one's going to care. Even in "The Black Suits," which tries unsuccessfully to translate the feel of a garage band meant to sound at least somewhat like Weezer to the stage, Iconis' songs all but leap out of a show that is at least a half-hour too long and has severe problems on a story level. If any composer in this movement seems most likely to write something that turns into a gargantuan hit, it's Iconis; it just probably won't be "The Black Suits," which is mostly useful as an example of how the indie-rock musical can fall short.

It's Malloy's "Natasha, Pierre, and the Great Comet Of 1812" — still playing in New York as of this writing — that most firmly suggests the possibilities of this boomlet of shows. Malloy might bristle at his show being called an indie-rock musical — its promotional materials describe it as "an electropop opera," and the influence of EDM is present throughout — but in its best moments, "Natasha" feels almost like being stuck in the middle of an Arcade Fire album. (The show is staged so that it takes place all around the audience, which can feel cloying and desperate but here feels somehow appropriate.) Again, the touchstones are hit: The musical is based on unlikely source material (a section of "War and Peace") and less concerned about how the lyrics will come across than about creating an emotionally overwhelming experience. (It certainly doesn't hurt that the show features the terrific Philippa Soo as Natasha; without her, it might crumble underneath its own artifice.) The show jumps ably from singer-songwriter-style folk to electronica to hard-charging rock, and it's hard to mistake it outside of a couple of numbers for anything else playing on Broadway.

"Natasha" speaks so thoroughly to the possibilities of this movement, because it seems at all turns like it's about to turn into pastiche or ironic meta-commentary — after all, it's a musical based on "War and Peace," and how crazy is that? — but it always veers away at the last second, and that's almost entirely driven by the music. Songs dip and curl in unexpected ways, and when the show finally pulls to its resolution at the end of Act 2, it's washed away not in orchestral fanfare but in a weird, beautiful confluence of noise. Indie rock is very often a bruised, sincere genre, made almost exclusively by sensitive white guys who seem like they're singing about getting picked on in high school for at least their first couple of albums, and Malloy, who took many of his lyrics directly from the novel "Natasha" was based on, seems an uncanny fit for the Hold Steady's Craig Finn, if Finn suddenly decided to start writing musicals. Like Finn, he's a bit older than many of his contemporaries, and like Finn, his lyrics can be oceans of words. But as in the best Hold Steady songs, the best moments in "Natasha" arrive with almost startling emotional directness, going straight for the heart, rather than the brain.

The indie-rock musical has yet to produce a true successor to "Spring Awakening's" reign as the only one of its ilk to run for more than a year on Broadway. And yet following this mini-surge of composers, who are all now working on seemingly impossible adaptations (Friedman on Jonathan Lethem's "Fortress of Solitude," Iconis on Hunter S. Thompson's life, and Malloy on "Moby-Dick"), suggests one possible, exciting future for the genre, one way to burst out of its niche and explore new territory. None of these shows is perfect, and all bite off ambitions bigger than they can chew. But one thing about them should make any fan of both Broadway and pop music thrill just a little bit: They all, finally, sound like now, not like an idea of what now might sound like if filtered through the original cast album of "Pippin."

Shares