For the movie industry, the culture industry and America in general, 2013 was the best of times and the worst of times. Well, except for the “best of times” part — I just put that in because it’s a literary reference, albeit one that gets used too often, and it has a nice rhythm to it. Still, it’s important to recognize, at the end of a year full of racial discord, disturbing revelations about our own government, political paralysis and near-total inaction on the issues that really matter, that the American picture is contradictory and paradoxical, rather than flat-out negative.

I don’t think it makes any sense at this point in history, if it ever did, to talk about “the year in movies” as if that could be divorced from any social or political context. Sure, some people are content to write year-end pieces from inside a self-referential bubble of empty symbolism, meaningless fluffery and puppet theater, devoid of any social meaning or relevance to ordinary people’s lives. And those are the political reporters! I’m here to talk about the serious stuff, like why Brad Pitt’s abolitionist-Canadian carpenter character in “12 Years a Slave” has such amazing hair (and doesn’t sound anything like a Canadian). Answer: That question answers itself.

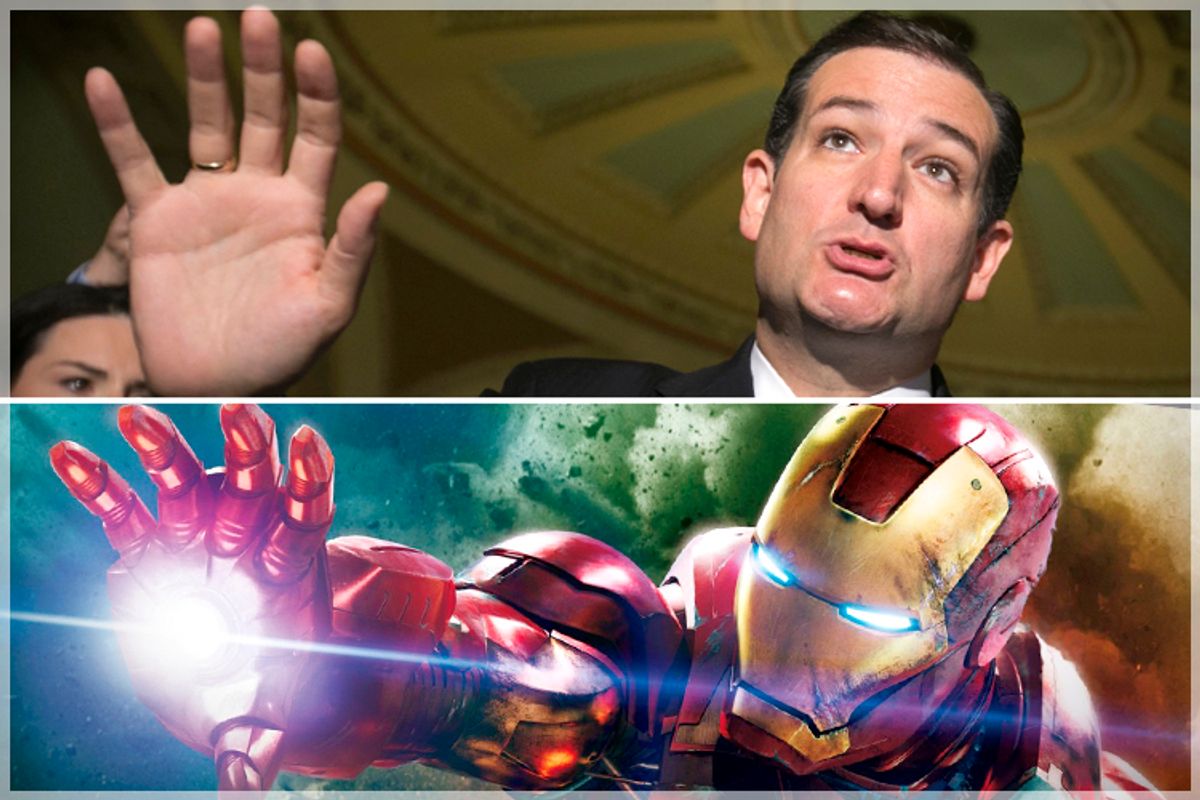

I’ve got Iron Man and Ted Cruz up there partly because it’s a funny combination, but also because they were the big winners of 2013 and maybe, taking the longer view, its big losers too. They’re a pair of sarcastic and charismatic assholes who are intelligent, vainglorious and badly in need of lessons in humility. It can be difficult to remember that, in the real world, Cruz is a junior member of the United States Senate, who is disliked by nearly all his colleagues and has almost no ability to get things done. He has branded himself almost overnight as the leader of a fervent, insurrectionist and newly energized right-wing movement, which claims it wants to save America from creeping socialism but seems suspiciously eager to destroy it instead. Cruz is surely one of the most loved, most hated and most feared men in America, but with the failure of the government shutdown, he is also almost certainly now past his apex of popularity. Barring an actual right-wing revolution, one involving bullets rather than ballots, Cruz will never be president, and will never be more powerful than he was this past summer and fall.

Robert Downey Jr.’s metal-clad superhero is also past his prime, but remains massively popular. I’m not suggesting any profound ideological parallels between Ted Cruz and Iron Man, by the way, although we could get partway there: They’re both ultimately defenders of power and privilege masked as other things, but at least Tony Stark does not pretend to stand for ordinary people. One could devote an entire article, or even a book, to decoding the incoherent politics of the Marvel universe (possibly someone has done this), which seem to teeter back and forth between post-1960s liberalism and full-on fascism.

At any rate, the “Iron Man” franchise went out on top, with its final installment piling up more than $1.2 billion in worldwide box office, making it easily the year’s top-grossing film. Yet “Iron Man 3” was a hit movie and really nothing more. You never felt like it generated tremendous water-cooler buzz, or compelled Op-Ed columnists to weave it into their copy. (That role, in 2013, belonged to “Breaking Bad.”) It would be stupid to suggest that the era of the superhero movie is over — not with Captain America and Spider-Man sequels coming next summer, and both Joss Whedon’s next Avengers movie and Zack Snyder’s “Batman vs. Superman” scheduled for 2015 — but I suspect it’s entering a long, slow period of decline, a decadent slide into the sunset. Superhero movies will make tons of money into the indefinite future, but the genre as currently constructed seems to have run into its inherent limitations, and we no longer need to convince ourselves it possesses mythic significance. Recently, we learned the news that Paul Rudd may be playing Ant-Man in an upcoming Marvel picture. I rest my case.

No one who made a movie released in 2013 had ever heard of Edward Snowden or George Zimmerman when their projects were launched, but those two ambiguous figures hovered over the cultural realm as over the political. Mistrust of government, the ruling elites and all forms of authority has long been a potent theme in popular entertainment, and the entire saga of Snowden, Glenn Greenwald and Laura Poitras seemed ripped from a wonky (if excellent) thriller. In the movies, paranoia was almost ubiquitous this year: “Iron Man 3” and “Star Trek Into Darkness” were driven by complicated conspiracy theories; “Gravity” captured the aftermath of a technological apocalypse; cowardly politicians surrender the world to monsters in “Pacific Rim”; a group of magicians stage class-warfare spectacles in the surprise summer hit “Now You See Me.” Most obvious of all, there was “The Hunger Games: Catching Fire,” a girl-power action flick about the birth of a revolutionary underground. It will out-gross its predecessor, both because it’s a better film and because it appeals to the disgruntled and disenfranchised across the political spectrum. Is Katniss Everdeen inspired by Lenin, by Emma Goldman or by Ayn Rand? Anyone who asks the question already knows what they think.

This was also the year of Zimmerman’s acquittal (and conversion into a permanent tabloid celebrity), Paula Deen’s public flameout and the Detroit bankruptcy, when we learned once again that America’s old-school black-white racial divide has definitely not healed. Although it was Ted Cruz, a Cuban-American born in Canada, who served as the leader of this fall’s government shutdown, his constituency is largely a lily-white, neo-Confederate nation within a nation, seeking to fight one last battle against the multicultural usurpers or simply burn the whole place down. Whether you choose to view this as coincidence, paradox or corollary, 2013 also brought us a remarkable mini-renaissance of black cinema at all levels of the business.

“Lee Daniels’ The Butler,” an unexpectedly big hit, told a traditional, sentimental and highly affecting fable of one African-American man’s journey from the Jim Crow South to the age of Obama, while serving as a silent witness to history. Steve McQueen’s harrowing “12 Years a Slave” brought the reality of America’s darkest historical chapter to the screen for the first time, seven decades after the racist agitprop of “Gone With the Wind.” Numerous overamped critics proclaimed “12 Years” the Oscar winner following its Toronto premiere, but that was almost certainly wishful groupthink. It’s no accident that this film was made by a British director with a largely foreign-born cast; even now, few Americans want to confront the subject of slavery directly, and the film’s modest commercial returns reflect that. (It’s earned about $35 million, and likely turned little or no profit.)

Ryan Coogler’s “Fruitvale Station,” perhaps the year’s most promising American debut film, turned a real-life tragedy — the killing of an unarmed black man by a police officer at an Oakland, Calif., train station — into an operatic fable of hope and possibility that is not entirely pessimistic despite its heartbreaking conclusion. As portrayed by the brilliant young actor Michael B. Jordan, Oscar Grant nearly lived to see an America where pre-written racial scripts would not dictate so much of what we say and do. He could imagine such a country, and may have believed it existed. Ultimately both he and the cop who shot him were in the grip of an ancient and poisonous narrative, the same one at work in “12 Years a Slave,” a narrative whose influence has waned but not perished.

One should never treat Internet commenters as representative of anything in particular, but I get the impression that some people who haven’t seen “The Butler” or “12 Years a Slave” or “Fruitvale Station” assume they are artless and accusatory documents of racial grievance, in which black people are depicted as suffering saints and whites as evil and sadistic. In fact, the films of this new black wave all take a complicated view of race relations, and are more interested in black people’s own agency than in dissecting white folks’ souls. In Ava DuVernay’s “Middle of Nowhere” and Andrew Dosumnu’s Nigerian-immigrant saga “Mother of George,” whites are nearly invisible. In Shaka King’s stoner comedy “Newlyweeds,” an interracial friendship sparks a hilarious blaxploitation parody involving a crime-fighting team. “Fruitvale Station” makes clear that fellow passengers on Oscar Grant’s commuter train, many of them white, used their cellphones to document what happened to him. Even the deranged Louisiana slave-owner played by Michael Fassbender in “12 Years a Slave,” who’s about as evil and sadistic as a person can get, is also a tremendously charismatic figure, a man seduced and perverted, Col. Kurtz-style, by a level of power over others that no human being should ever possess.

Maybe it’s also paradoxical that African-American cinema has this moment of flowering just as the multiracial character of America’s future is becoming clear and the black-white paradigm seems increasingly outmoded. But as history, psychology and mythology all teach us, you have to deal with the past before you can confront the future, and our divided, conflicted and imprisoned nation is still struggling with that one. Two of my favorite films of the year have nothing to do with race relations or the misuse of power, but both find meaning in excavating the past. In “Inside Llewyn Davis,” the Coen brothers take us to 1961 Greenwich Village for a heartbreaking and mysterious fable of artistic failure, while in the documentary “Stories We Tell,” Sarah Polley explores the unanswered questions in her own Anglo-Canadian family, as well as the fact that what we think we know about the past is never complete or true. Those are lessons to take to heart, and films that will be remembered when “Iron Man 3” is an indistinguishable blur and Ted Cruz a trivia answer. My top-10 list is coming soon! Happy holidays, everybody.

Shares