Salon reached out to a bunch of writers who had new books out this year to find out what their favorite book of the year was. We saw a lot of books by big-name writers: Donna Tartt, Jonathan Lethem and Elizabeth Gilbert, just to name a few. But 2013 was a good year for lesser-known writers, too. Here are some titles you should add to your to-be-read piles. Now you just have to find the time to read them.

James McBride, author of “The Good Lord Bird” (Riverhead)

“Drama High: The Incredible True Story of a Brilliant Teacher, a Struggling Town, and the Magic of Theater,” by Michael Sokolove (Riverhead)

My pick of the year is “Drama High” by Michael Sokolove. It's a wonderful book by a very gifted writer. Sokolove goes back to his old high school, located in a bland, otherwise unremarkable Philadelphia suburb, and tells the story of a superbly gifted high school drama teacher who changed his life and the lives of countless high school kids over the course of decades. A talented schoolteacher who moved the world through music and song. Deeply researched and very well written. I enjoyed it.

Jonathan Alter, author of “The Center Holds: Obama and His Enemies” (Simon & Schuster)

“Ike’s Bluff: President Eisenhower’s Secret Battle to Save the World,” by Evan Thomas (Back Bay Books)

"Ike's Bluff: President Eisenhower's Secret Battle to Save the World," by Evan Thomas, is a gripping and eye-opening story about a president long depicted as old and out of touch when he reached high office. We came close enough to nuclear war during the 1950s to make even a yellow dog Democrat like me glad that Ike, not Adlai Stevenson, was in the White House. Only Ike had the experience, cunning and credibility with the military to keep the peace at the height of the Cold War. Thomas, one of our greatest narrative historians, is at the top of his game here.

Matt Bell, author of “In the House Upon the Dirt Between the Lake and the Woods” (Soho Press)

“Spectacle,” by Susan Steinberg (Graywolf Press)

Aggressive and moving, funny and smart, the formally innovative stories in Susan Steinberg's “Spectacle” thrill like few others. Steinberg's narrators circle their subjects with a style all her own, asserting and then undoing their assertions, subverting the ground they've begun to establish. Sentence after sentence they perform, finely tenuous performances of gender and power and authority unpacking obsessions with men and plane crashes, lust and death. I've been so obsessed with this book that I pitched an interview, taught the book, celebrated it with friends and read and reread its stories month after month. In a year of great story collections, this one was my favorite.

Lauren Beukes, author of “The Shining Girls” (Mulholland Books)

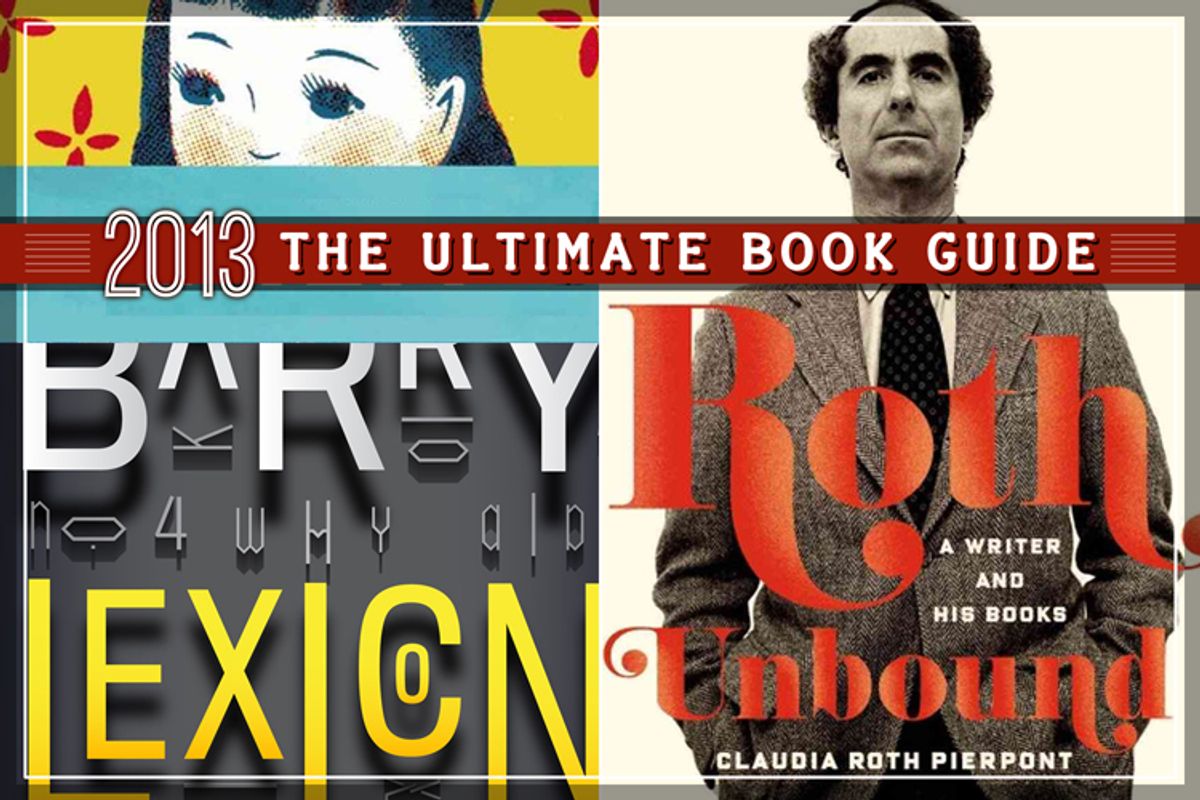

“Lexicon,” by Max Barry (Penguin Press)

I've read a lot of amazing books this year, from “We Need New Names” to “Claire de Witt and the Bohemian Highway” and “Fatale, “ but Max Barry's “Lexicon” was the novel that burrowed into my head and lodged there like some horrible brain-parasite. On the first page, he rips the carpet out from under you, and then drops the ground away too. Barry takes a neat thriller conceit – what if neurolinguistic programming is real and language words do have power and there’s a secret society with agents named for dead poets who control them – and turns it into something profoundly more ambitious and surprising. It’s brutal and twisty and at the same time full of terrible empathy for who we are in the world and what words mean – especially that easy cliché, “love.”

Kelly Braffet, author of “Save Yourself” (Crown)

“The Panopticon,” by Jenni Fagan (Hogarth)

I loved Jenni Fagan’s “The Pantopicon.” It’s one of those rare and wonderful novels that feels both classic and fresh. It simultaneously hearkens back to both the Lost Teenager books I once loved and the razor-blade sharp mid-century crime novels I love still, but Anais and her world feel altogether new. It’s not your typical crime novel, or your typical kid-all-alone-in-this-crazy-world novel, or your typical anything, and I found it incredibly refreshing and exciting

Emma Brockes, author of “She Left Me the Gun: My Mother’s Life Before Me” (Penguin Press)

“The Examined Life,” by Stephen Grosz (W.W. Norton & Company)

Stephen Grosz is an American psychoanalyst living in London who, in “The Examined Life,” chronicles 31 of his most interesting cases over the course of a 25-year career. The writing is taut, aphoristic but specific – Michiko Kakutani likened it to Chekhov, with good cause. Some cases end well, others not, but you always identify with the sufferer. “I was every single person in that book, including the spitting boy,” said a friend of mine, referring to the case study of a disturbed adolescent and an amazing feat of empathy for the writer to pull off. There's woe in “The Examined Life” and yet you came away feeling ignited and consoled.

Stephen Burt, author of “Belmont” (Graywolf Press)

“Enchantée,” by Angie Estes (Oberlin College Press)

It's been a good year for poems of many kinds -- rough and raw, border-testing and avant-garde, more conventionally elaborate -- and so it's hard for me to pick one favorite, but for pure pleasure in the curves and surfaces, the glittering facets and darker recesses, of language, it's hard if not impossible to top Angie Estes's “Enchantée.” Estes has been writing for a few books now about the attractions of art, old and new, fine and applied, about how we can (and about why she feels she must) defend the idea of beauty itself. Now she's connected those complicated attractions to a sense of mourning, a drive to commemorate. “Enchantée” has much to do (if I read it right) with the death of her parents, with her sense of being alone in the world, but that sense gets bolstered, or succored, by the arts, sculptural, literary, sartorial, even culinary, as in her poem called "Dessert," where words and memories "rustle/ like elves in the leaves, so the French/ call them lévres, the levers, lapels,/ of the mouth, where we lapse/ into ourselves."

Lee Child, author of “Never Go Back” (Delacorte Press)

“One Summer: America, 1927,” by Bill Bryson (Doubleday)

Every year dozens of books stake a legitimate claim as the most enjoyable, but the ultimate winner always has a sense of irresistible flow, as if the reader is being pulled along at a breakneck pace, while being absolutely unaware of it -- like wallowing in a warm bath that's actually rushing like a river. Bill Bryson's portrait of the U.S. 86 years ago did that for me. 1927 was the summer of Babe Ruth's 60 home runs, and Charles Lindbergh's aviation triumphs, and also a whole lot of other weirdness that makes you think, yes, 1927 was a long time ago, but in some ways is as familiar as yesterday.

Michael Connelly, author of “The Gods of Guilt” (Little, Brown and Company)

“Act of War: Lyndon Johnson, North Korea and the Capture of the Spy Ship Pueblo,” by Jack Cheevers (NAL Hardcover)

“Act of War: Lyndon Johnson, North Korea and the Capture of the Spy Ship Pueblo” by Jack Cheevers is a riveting account of international politics and the very real human drama of the crew of the rag-tag spy ship taken hostage in 1968. Cheevers' research is relentless and he masterfully takes us from the high seas of the Pacific to the highest offices in Washington to turn this story into an absorbing page turner about the indomitable spirit of survival.

Caleb Crain, author of “Necessary Errors” (Penguin Books)

“Thank You, Anarchy: Notes from the Occupy Apocalypse,” by Nathan Schneider (University of California Press)

A year after Occupy Wall Street, a New York Times finance reporter claimed that it deserved no more than "an asterisk in the history books." Two years after Occupy, the movement has received a history book of its own. Nathan Schneider writes as a participant-observer, sympathetic but clear-eyed. He reports on arguments without refighting them; he reminds the reader what the Kool-Aid tasted like without insisting that it be drunk anew. In Occupy's heyday, interpretation proliferated, in a way that sometimes obscured significance. I found Schneider's plainspoken chronicle grounding and clarifying.

Junot Díaz, author of “This Is How You Lose Her” (Riverhead)

“A Tale for the Time Being,” by Ruth Ozeki (Viking)

Ozeki is one of the smartest (and funniest) writers I know, and in this novel she flat-out knocks it out of the park. “A Tale for the Time Being” is as layered and mysterious as life and it's overwhelmingly wise, reaching across lands and language and time to show the unity, solitude, confusion and hope at the heart of the human experience. A powerful, beautiful book.

Pamela Erens, author of “The Virgins” (Tin House Books)

“Roth Unbound: A Writer and His Work,” by Claudia Roth Pierpont (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Most biographies of writers are heavy on minutiae and surprisingly unilluminating about artistry. Roth Pierpont (no relation to Philip) dispenses with the unnecessary, invoking Roth’s life only to the degree that it extends our understanding of the work. She’s a fan, but a clear-eyed and unfawning one. And she writes terrifically well herself, offering intelligent, intuitive readings while making a convincing case for the cohesion of Roth’s oeuvre -- the supposed duds often being transitional works on the path to new breakthroughs. The man, too, comes alive in this compulsively readable appreciation.

Elizabeth Gilbert, author of “The Signature of All Things” (Viking)

“Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened,” by Allie Brosh (Touchstone)

There are books that we admire but do not love. There are books that we love but do not admire. And then there are books that we both admire and love, which is the rare and awesome literary sweet spot for any reader. For me this year, that sweet spot got totally hijacked by Allie Brosh and her hilarious, devastating and surprising "Hyperbole and a Half."

Matthew Goodman, author of “Eighty Days: Nellie Bly and Elizabeth Bisland’s History-Making Race Around the World” (Ballantine Books)

“Cotton Tenants: Three Families,” by James Agee (Melville House)

James Agee’s "Let Us Now Praise Famous Men" is a vast, often exhilarating, occasionally exasperating work that moves from a description of three Alabama sharecropper families into something like a meditation on the sacredness of human existence. It began life in 1936 as an article rejected by Fortune magazine; long believed to be lost, that article has now, happily enough, been published as "Cotton Tenants." Here we see the young Agee developing his already considerable journalistic skills – his anger simmering, he patiently traces the horrifyingly meager constituents of his subjects’ lives – while also bringing to bear the literary gifts that allowed him, for instance, to observe of a tenant farmer, “Like many people who cannot read or write he handles words with a clumsy economy and beauty, as if they were farm animals drawing open difficult land.”

Joe Hill, author of “NOS4A2” (William Morrow)

“The Shining Girls,” by Lauren Beukes (Mulholland Books)

In Chicago, there's a house, a brownstone, that's reeling through time like a drunk on the disco floor. Look out the windows and you can see the months twitching past at the dizzying speed of time-lapse photography, years jittering by in minutes, skyscrapers rising in a mesh of scaffolding, gleaming for a few moments, then vanishing, only to be built again. The front door opens into the thirties one moment, the nineties the next... and a sick puppy named Harper Curtis is the man in possession of the house keys.

Harper has been set loose on history itself, and his time-skipping apartment building is the perfect getaway vehicle for a budding serial killer who strolls across the page like one of Faulkner's more remorseless creatures. You'll find Harper -- and the sweet punk named Kirby Mazrachi who battles him -- in Lauren Beukes' fabulous thriller “The Shining Girls.” Beukes' mastery and heart will keep you turning pages all night and her prize monster will haunt your dreams (always assuming you can get to sleep at all). Harper Curtis is a nightmare big enough to cast a shadow over the length of what has sometimes been called The American Century. That's all right. "Let's face it, [Harper] thinks, America had it coming."

Elliott Holt, author of “You Are One of Them” (Penguin Press)

“The Flamethrowers,” by Rachel Kushner (Scribner)

I fell hard for Rachel Kushner's kinetic second novel "The Flamethrowers." The book's heroine, Reno, is a motorcycle racer and budding artist who falls in love with an older (and far more successful) artist, a man named Sandro whose wealthy Italian family manufactures motorcycles. Kushner's prose is wry and electric -- the book never failed to surprise me on a sentence level -- and the story is an ambitious and vivid portrait of 1970s New York and Rome, as well as the politics of art and desire.

Samantha Irby, author of “Meaty” (Curbside Splendor)

“Hyperbole and a Half: Unfortunate Situations, Flawed Coping Mechanisms, Mayhem, and Other Things That Happened,” by Allie Brosh (Touchstone)

A couple years ago I was sulking at my desk, pretending not to be stalking my ex-boyfriend on Facebook while at work, when one of my friends sent me an email. “HOLY SHIT DUDE THIS IS TOTALLY US” was the subject line, the body empty save for a link to the blog Hyperbole and a Half and a post called “This is Why I’ll Never be an Adult.” It was magical, bro. And now Allie Brosh’s amazing blog is a book. Homegirl is smart and hilarious and uses crude computer drawings to make us feel all of the feels about being irresponsible and hating spicy foods and loving dogs and trying to grow up right. It’s a goddamned jam.

Adam Johnson, author of “The Orphan Master’s Son” (Random House)

“A Constellation of Vital Phenomena,” by Anthony Marra (Hogarth)

Something about the consumerism and excess of the holiday season makes me want to engage books with a serious dimension. Over your winter break this year, I recommend Anthony Marra’s National Book Award nominated “A Constellation of Vital Phenomena.” This gripping and powerful debut novel is set in the all-too-real Chechen conflict and interrogates the very underpinnings of love and sacrifice. Remarkable and breathtaking, this sweeping story is filled with beauty and humor and heart, and the bravery of its central characters is sure to serve as an antidote to holiday commercialism and a reminder of what’s most important in life.

Boris Kachka, author of “Hothouse: The Art of Survival and the Survival of Art at America’s Most Celebrated Publishing House, Farrar, Straus and Giroux” (Simon & Schuster)

“Dissident Gardens,” by Jonathan Lethem (Doubleday)

There’s a feeling of vicarious triumph — joy tinged with pride — in seeing a novelist you’ve faithfully followed through every win and loss finally, truly hit it out of the park. Jonathan Lethem did it this year with “Dissident Gardens,” a saga, capacious but controlled, about three generations of leftists who love, fight and fail, each in her own manner and time. Lethem is celebrated for blending realism and fantasy, but here he runs full-throttle on the first and uses the second very sparingly — as a turbo boost, involving Archie Bunker, that propels the novel into posterity.

Owen King, author of “Double Feature” (Scribner)

“The Flamethrowers,” by Rachel Kushner (Scribner)

Some great novels beguile you, ingratiate themselves, quietly infect you with an itch you can’t understand or stop digging at. Rachel Kushner’s “The Flamethrowers” is another kind of book: it puts a clamp on you immediately with a scene of beautifully, precisely described violence that upends the expectations of coolness that one might well bring to the reading of a novel whose subject is, ostensibly, “the New York art world of the nineteen-seventies.” While “The Flamethrowers” does concern the New York art world of the nineteen-seventies, it’s country miles from the museum, white walls and artifacts under glass. “The Flamethrowers” is alive! Kushner refuses to be reverent toward her characters or their projects. Reno, the author’s primary eye, is an observer and recorder of the highest order, at once empathetic and marvelously aware.

Olivia Laing, author of “The Trip to Echo Spring” (Picador)

“My 1980s & Other Essays,” by Wayne Koestenbaum (FSG Originals)

I'm excited by Wayne Koestenbaum's excitement. His new collection of cultural criticism, “My 1980s & Other Essays,” is definitely the most beautiful book I saw all year, with Debbie Harry gazing wide-eyed from the cover. But the inside's even more alluring: 39 short essays, most of them constructed by way of pleasurably dense and allusive numbered paragraphs that dart between the erotic and the poetic. Zipping busily from anecdotes about gate-crashing an opera singer's funeral or jerking off while reading Gore Vidal to the joyful matter of Frank O'Hara's exclamation marks, Koestenbaum is adept at making even the densest material open up in magical and unexpected ways. It's hard to think of anyone who makes such light work of serious thought. I love his writing assignments too. Koestenbaums in miniature, they perform an elegant resistance against cliché, pedantry, dullness in all its guises.

J.M. Ledgard, author of “Submergence” (Coffee House Press)

“The African,” by J.M.G. Le Clezio (Godine)

You know the purity of distillation by the richness of what remains. In a mere 128 pages, in this memoir of growing up in wild Iboland in the 1940s, Nobel laureate J.M.G. Le Clezio says more about childhood, service and Africa than many writers have achieved in volumes. Le Clezio's heroic and tyrannical father was the only doctor in a district of what is now eastern Nigeria. Le Clezio says that world of tall grasses, clay figurines of gods, pallid termites, red earth blazing, storm clouds gathering, bodies living so vitally or again so rotted out and diseased, "is all so far away, so close." As our ability to put reflection above streaming diminishes, I am certain that “The African” will become a precious volume for anyone who asks what went before.

J. Michael Lennon, author of “Norman Mailer: A Double Life” (Simon & Schuster)

“Astonished: A Story of Evil, Blessings, Grace, and Solace,” by Beverly Donofrio (Viking)

This is the story of a sabbatical, but not from teaching. After being raped in Mexico, Donofrio lives in retreat houses in the American West where she confronts the evil forces that file through the hole in her soul created by the rape. She cries, prays, watches birds and throttles her narcissism. Spiritually sore, she comes to understand St. Paul’s words: “When I am weak, I am strong.” An ardent feminist, she forgives and undergoes a sea change in the desert. Written with mordant humor, searing honesty, and an eye for the mysteries of love, nature and monkish life.

Cari Luna, author of “The Revolution of Every Day” (Tin House Books)

“You Only Get Letters from Jail,” by Jodi Angel (Tin House Books)

Confession: I had two favorite books this year, but one of them is Rachel Kushner’s “The Flamethrowers” and I’m confident she’ll be getting plenty of love from other contributors to this list. My other, equally adored, favorite of 2013 is Jodi Angel’s breathtaking story collection, “You Only Get Letters from Jail.” It’s heartbreakingly good, sinking the reader down deep into a world of teenage boys at loose ends, their confusion, their longing, their muscle cars... Angel’s insight, empathy, and pitch-perfect ear for dialogue are astonishing, and the boys and their stories follow me still, months after I read the last page.

Anthony Marra, author of “A Constellation of Vital Phenomena” (Hogarth)

“The Woman Who Lost Her Soul,” by Bob Shacochis (Atlantic Monthly Press)

“The Woman Who Lost Her Soul,” a showstopper (and doorstopper) of a novel by Bob Shacochis, is an atlas of the ways political violence corrupts both the individual and national consciousness. Moving among multiple countries over the course of decades, it traces the failures, achievements, perversions and deceptions of late-20th-century American foreign policy. Over the course of its many pages, the prose is never less than lyrical, personal and intelligent, but the real reason to read is to witness the near superhuman ambition of Shacochis’ undertaking. If he were a rower, this would be a circumnavigation of the globe. If he were a sculptor, this would be Mount Rushmore. Lucky for us, he’s a writer and “The Woman Who Lost Her Soul” is a masterpiece.

Colum McCann, author of “TransAtlantic” (Random House)

“Someone,” by Alice McDermott (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

I always have a hard time choosing "best books." I always end up with the conclusion that literature is not an Olympics -- nobody should ever get the gold medal, since there's no such thing. That said, I have just finished Alice McDermott's "Someone," and I think it's possibly one of the finest books I have ever read. I hardly know what to say about it except that it restored my faith in the literary experience: it was the sort of novel that reminded me of why I read, and why I write. I will carry it with me for a long long time.

Claire Messud, author of “The Woman Upstairs” (Knopf)

“Schroder,” by Amity Gaige (Twelve)

Amity Gaige’s “Schroder” is simultaneously a literary tour de force and an utterly compelling read. An homage to Nabokov’s “Lolita” with a gesture toward recent newspaper headlines, it is above all a novel entirely its own. Erik Schroder, an immigrant from East Germany, has lived his entire adult life as Eric Kennedy. His invented past has determined his present. Now, he finds himself on the lam with his young daughter following a messy divorce; at stake is not just their relationship, but his entire life. Gaige creates, in Erik Schroder, a character whose complexities, while shocking, are thoroughly human and recognizable. This novel will alter your perspective – as only great novels can do.

Ann Patchett, author of “This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage” (Harper)

“A Constellation of Vital Phenomena,” by Anthony Marra (Hogarth)

There were so many exceptional books this year, but Marra gets extra points for taking subject matter I would normally avoid (the war in Chechnya) and making it into a novel I couldn’t put down. He manages so many characters, so much violence and human complexity, and brings it all to an astonishing conclusion. I read it in January and I haven’t stopped thinking about it.

Benjamin Percy, author of “Red Moon” (Grand Central Publishing)

“The Goldfinch,” by Donna Tartt (Little, Brown and Company)

Donna Tartt is probably sick of hearing her work described as "Dickensian," but the comparisons to “Oliver Twist” and “Great Expectations” are inescapable. Still, I'll try to be more original. Majestic -- how's that for a satisfactory adjective? Baroque. Sprawling. Unforgettable. Painfully beautiful (shit, that's two words -- can I do that?). However you sum it up, this book owned me for several weeks, and now I find myself pushing it on everyone I know and often thinking about its characters as though they were a part of my life. (I wonder what Boris is up to right now? Probably eating herring and drinking vodka and plotting something fun but illegal.) It's an extraordinary accomplishment, and I wish I didn't have to wait a decade before Tartt puts out her next novel, but if that's what it takes to produce something this...Dickensian, then so be it.

Norman Rush, author of “Subtle Bodies” (Knopf)

“For the Republic: Political Essays,” by George Scialabba (Pressed Wafer)

George Scialabba’s “For the Republic: Political Essays” is my choice for 2013’s best book. Best, here, means most relevant, acute and intellectually helpful in interpreting our peculiar political present. These essays, by arguably the deepest observer produced by the independent left over the last 30 years, concentrate on prominent players in the commentariat (social critics like Thomas Friedman, Roger Scruton, Michael Sandel, Stanley Fish, Jonathan Haidt) with clarifying effect. Scialabba writes with concision and style. Readers new to this wry but fair-minded analyst will want to read his larger 2009 collection, “What Is an Intellectual For?” Scialabba’s work answers that question.

Saïd Sayrafiezadeh, author of “Brief Encounters with the Enemy” (The Dial Press)

“Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life,” by Dani Shapiro (Atlantic Monthly Press)

This is as much for those who have ever written as it is for those who have ever wondered what it’s like to write. Dani Shapiro doesn’t flinch from describing the grueling unnecessary necessity of creating art. Nor does she flinch from describing her journey to becoming a professional writer, including her Orthodox Jewish upbringing that informs so much of her material. Even so, this book will make the perfect stocking stuffer for the writer in your life. It’ll comfort them during their frequent tortured moments. They can read it like I did, with the covers pulled up to their chin.

Dani Shapiro, author of “Still Writing: The Pleasures and Perils of a Creative Life” (Atlantic Monthly Press)

“A Tale for the Time Being,” by Ruth Ozeki (Viking)

Ruth Ozeki's “A Tale for the Time Being” is one of those rare books -- I can list them on one hand -- that broke a long, parched spell of literary ennui for me. Here is a novel wholly original -- one that forges new ground without flexing its muscles. A novel that tackles big themes -- the nature of time and reality -- while never compromising its beating heart. A bold, deeply thrilling book.

David Shields, author of “How Literature Saved My Life” (Vintage)

“The Complete Smoking Diaries,” by Simon Gray (Granta)

My favorite book of 2013, one of my favorite books ever written, and easily available in the U.S. from Granta UK, is Simon Gray’s “The Complete Smoking Diaries,” a post-post-postmodern “In Search of Lost Time”: rigorously/relentlessly self-mocking and self-scrutinizing, all while pretending to be just out on a lark; brilliantly orchestrated into a sustained thematic, psychological and philosophical whole, its 864 pages yielding nothing less than the literary equivalent of Rembrandt’s last self-portrait; unbelievably beautiful, unbelievably great, utterly loneliness-assuaging.

Matthew Specktor, author of “American Dream Machine” (Tin House Books)

“A Man in Love,” by Karl Ove Knausgaard (Archipelago)

2013 was all about Karl Ove Knausgaard, for me. The second volume of "My Struggle" was published in translation by Archipelago Books last spring, and it's just as mesmeric as the first. It seems absurd, if not impossible, for a book that reckons so directly with barely transmuted autobiographical experience, with a really very ordinary childhood, adulthood, young manhood, to possess such massive power. Somehow, it does. By sheer force of his intelligence, observation, memory and self-sympathy, Knausgaard sidesteps pitfalls that seem inevitable (narcissism, exhibitionism, just plain being boring), and restores to regular life a kind of grandeur. It's incredible.

Laura van den Berg, author of “The Isle of Youth” (FSG Originals)

“Mira Corpora,” by Jeff Jackson (Two Dollar Radio)

To read Jeff Jackson’s “Mira Corpora” is to enter into a trance state. A hypnotic, brutal, and lyric exploration of youth, trauma and the construction of memory, this novel is like nothing I’ve ever read before and is, unquestionably, one of my favorite books published this year.

Juan Gabriel Vásquez, author of “The Sound of Things Falling” (Riverhead)

“Dissident Gardens,” by Jonathan Lethem (Doubleday)

In the first 50 pages of “Dissident Gardens,” Miriam is described as a “Bolshevik of the five senses”; her mother, Rose, needs to “live forever, a flesh monument, commemorating Socialism’s failure as an intimate wound.” In Lethem’s novel, the old distinctions between the personal and the political, between the public struggle and the private predicament, have ceased to exist. Lethem brilliantly brings to life three generations of American revolutionaries, from the card-carrying communists of the ’50s to the turn-of-the-century Occupy activists, and he looks at them with as much generosity as skepticism. His sentences are dazzling and his people are fascinating. This is a wonderful achievement.

Adelle Waldman, author of “The Love Affairs of Nathaniel P.” (Henry Holt and Co.)

“A Dual Inheritance,” by Joanna Hershon (Ballantine)

One of my favorite books of 2013 was “A Dual Inheritance” by Joanna Hershon, a sweeping, character-based novel — the kind of book you get deliciously lost in over a long weekend or a vacation. About two very different men who meet at Harvard in the 1960s, the novel follows them through the next 50 years, tracking their marriages, careers and children. Like Jonathan Franzen’s, Hershon’s characters jump off the page, and the shifting settings — from Cambridge to New York to Africa — and evolving social context are wonderfully rendered. It’s also a classic love story, with a love triangle at its center and an ending that is both satisfying and unsentimental.

Teddy Wayne, author of “The Love Song of Jonny Valentine” (Free Press)

“The Night Gwen Stacy Died,” by Sarah Bruni (Mariner Books)

Sarah Bruni’s debut novel, “The Night Gwen Stacy Died,” is so many genres at once — an unsentimental love story about two outsiders, a literary coming-of-age tale about an Iowa girl’s maturation in the big city (Chicago), a Bonnie-and-Clyde crime caper, a mystery, a thriller, a revisionist Peter Parker narrative — that, ultimately, it flouts them all. Bruni’s offbeat characters and incisive wit are folded into prose as smooth as the surface of Lake Michigan, and while the title refers to two famous Spider-Man comics, you need no prior knowledge or fandom of it to enjoy her wonderful novel.

Meg Wolitzer, author of “The Interestings” (Riverhead)

“The Goldfinch,” by Donna Tartt (Little, Brown and Company)

I was just having a conversation about Donna Tartt’s novel “The Goldfinch” with a friend, both of us marveling at how much we enjoyed it. This was a book we each wanted to return to at the end of a day, and we wondered what made it that way. Storytelling? Characters? Prose? It's hard to define exactly where the power of this book is concentrated. But somehow “The Goldfinch” had a hypnotic effect on me, as if it were a bottle marked "Read Me" -- and I did, happily.

Daniel Woodrell, author of “The Maid’s Version” (Little, Brown and Company)

“Nothing Gold Can Stay,” by Ron Rash (Ecco)

The book I keep returning to from this year is “Nothing Gold Can Stay” by Ron Rash. Sturdy, sly and artful stories rooted in a world I recognize, steep hillsides, limited horizons, homemade meth and old Celtic dreams. Rash is also a wonderful poet and you can hear that in his sentences and feel it in his presentation of character. There’s a big heart here, but no flinching from those human predicaments that even goodwill and empathy can’t fix.

Mitchell Zuckoff, author of “Frozen in Time: An Epic Story of Survival and a Modern Quest for Lost Heroes of World War II” (Harper)

“Junius and Albert’s Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey,” by Peter Carlson (PublicAffairs)

Bestsellers don’t need my help. Instead I’d like to plug the best book I read this year, Peter Carlson’s “Junius and Albert's Adventures in the Confederacy: A Civil War Odyssey.” This is a superbly researched and written true story of two remarkable reporters whose bravery, friendship and pluck carried them through an excruciating ordeal as captives inside Confederate prisons. Carlson gives us a narrative view of the war from the unique vantage point of these beleaguered buddy protagonists. He brings them, their tormentors and their helpers to life with deft strokes that make me wish I’d written this book.

Shares