From the days of Ben Franklin and his chart-obsessed "Autobiography," the American self has been a perpetual work in progress. (Franklin recommended keeping careful records of one's observance of such virtues as industry, temperance and cleanliness.) For the bemused, anxious and thoughtful writer Jessica Lamb-Shapiro, however, this mania has been especially pervasive. Her father, a child psychologist, has been writing self-help books for parents and children since before she was born, and even started a mail-order catalog of therapeutic toys and games, most of which he tested on her. Here's Lamb-Shapiro's recollection of the first time he coaxed his little daughter into playing a "cooperative game":

Dad: Everyone has to finish the game, or no one wins.

Me: What?

Dad: No one wins unless everyone wins.

Me: So no one wins.

Dad: No, everyone wins.

That conversation perfectly captures the spirit of "Promise Land: My Journey through America's Self-Help Culture," Lamb-Shapiro's deadpan, eyebrow-arched effort to comprehend the glass-half-full point of view despite her own half-empty propensities. There's no shortage of books featuring "cultural history" and other quasi-sociological surveys of this terrain, but Lamb-Shapiro's take is different. Part experiential journalism, part memoir, "Promise Land" is both funnier and more searching than detached forms of social commentary could ever hope to be.

The core of the book is Lamb-Shapiro's relationship to her father. He comes across as a (far) less annoying variant on Patch Adams. He once turned up at her school wearing a full gorilla costume and "thought it was funny to pay highway tolls wearing a hand-puppet." She adds, "with one exception, toll workers did not find this amusing in the least." When he dropped Jessica off at school in the morning, he'd invariably remind her that today was the first day of the rest of her life. Yet he raised a young woman who's afraid of "crowds, elevators and heights" and who once took a four-day train ride across country to avoid flying, spending most of that time in her berth because the train attendants had taken to calling out "Here comes New York!" whenever she walked into the dining car.

Still, father and daughter are clearly close, and "Promise Land" opens with the two of them attending a weekend conference on how to become a self-help guru, led by self-help guru (and "Chicken Soup for the Soul" creator) Mark Victor Hansen. "It didn't take long," Lamb-Shapiro writes, "for me to be struck by the irony of self-help writers being told how to help themselves, as well as the special sadness that attends the relinquishing of authority from an expert to a super-expert." In the course of "Promise Land," Lamb-Shapiro takes in a seminar on "The Rules," a dating guide for marriage-minded women; walks over hot coals at a New Age gathering for teens; becomes her dad's sidekick during his brief and inexplicable vogue as a media expert on a dangerous adolescent fad called the choking game; helps her friend Cynthia create a weirdly effective "vision board"; joins a fear-of-flying group employing the techniques of cognitive behavioral therapy; and works as a volunteer at a "grief camp" for kids aged 7 to 17 who have lost a parent or sibling.

The last experience strikes particularly close to home, for Lamb-Shapiro's mother died before Jessica's second birthday. It's not until rather late in the book that the cause -- suicide -- is revealed. From this fundamental loss comes Lamb-Shapiro's conviction that, "sometimes the only solution is to accept that there is no solution; that certain things have to be endured; that they cannot, should not, be fixed." Having a therapist father who tried his frantic best to convince her (and himself) that they were both strong enough to survive her mother's death has given Lamb-Shapiro an acute sense of how the therapeutic language of "feelings" can obfuscate. In such situations, "the very act of addressing an emotion represses it" and "the performance of communication supplants real communication" because "structure is imposed on emotional chaos, a structure so inherently incompatible that the emotion must retreat into the recesses of one's brain, never to return."

This is the profoundly skeptical attitude Lamb-Shapiro brings to such self-help premises as positive thinking and the law of attraction. She depicts herself as a less narcissistic female version of the self-deprecating, deeply neurotic character Woody Allen portrayed on screen and in his stand-up acts. This is a woman who nods all the way through the exposure therapy and group sharing in her fear-of-flying class -- the regimen that's supposed to culminate in the entire class boarding a plane for Boston -- all the while thinking, "I had no intention of getting on that flight." When her phobia counselor recalls once donning a fake cast to avoid participating in neighborhood activities, Lamb-Shapiro is transfixed with admiration for the woman's "creative genius."

Lamb-Shapiro's outsider perspective gives "Promise Land" its sardonic humor, but reality also seemed determined to cooperate by serving up irony after irony. At the seminar on "The Rules," a testimonial is offered by a woman who explains that she used the technique to captivate and marry an abusive man she ended up hating. After leaving him, she went right out to a singles dance and selected a new candidate. "'We just got married this morning at city hall!' Betsy shrieked, holding up her newly bejeweled ring finger. 'My divorce just came through yesterday!'" At the Mark Victor Hansen conference Lamb-Shapiro meets another woman who lives in the Disney-designed town of Celebration, Fla., and who's writing a book on "making homemaking fun, using Disney principles. For example, have an 'opening time.'"

"Promise Land" also features shrewd observations on the way self-help culture assures its acolytes that the best path to individual happiness is through following a universal formula. In this, Lamb-Shapiro zeroes in on the paradox at the heart of the American dream: that everyone can realize his unique value by subscribing to a uniform standard of "success" and pursuing it in exactly the same way as everyone else. She's particularly funny on the "law of attraction" school of self-help represented by such books as "Think and Grow Rich" and, mostly recently, "The Secret." These tracts swear that simply by believing you will get something (typically money), you will cause it to come to you. They also never get around to directly stating or describing this "secret" method; you're supposed to absorb it by osmosis, apparently. And despite being all pretty much the same, these best-sellers also all pretend to have discovered momentous, hidden truths. "I don't know anything about rocket science," Lamb-Shapiro retorts, "but that doesn't make rocket science a secret.

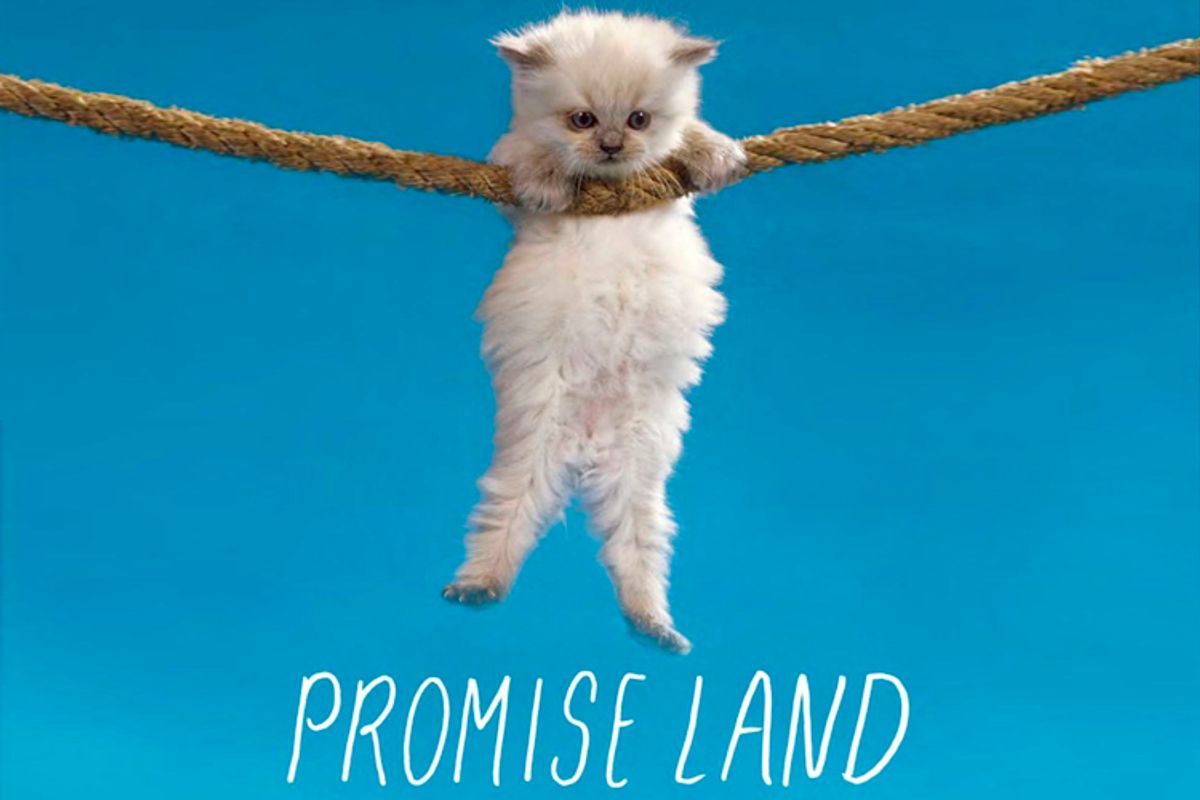

What Lamb-Shapiro does know a lot about is language, and even the self-help proponents she finds worthwhile have a tendency to put her off with their clichés and mushy terminology, buzzwords like "life-altering passage" and "healing circle." Her "allergy" to this lingo derives in large part from her sensitivity to the way that words professing to name the truth can instead be used to mute it. Yet in the end, even Lamb-Shapiro finds herself recognizing that merit hides in the most banal self-help maxim of all (which you can guess easily enough with a glance at the book's cover image of a kitten dangling from a twig). "Can even the most bastardized, laughable incarnations of self-help carry some kernel of redeeming value?" she asks herself. There's the rub, because (as the late David Foster Wallace was wont to affirm), indeed they can. Sometimes even the smartest among us find ourselves with nothing to fight off the encroaching night but a well-worn incantation. And sometimes, even if only sometimes, it's enough.

Shares