Two major legal challenges currently threaten the contraception mandate of the Affordable Care Act, and both are really important.

The first of these cases was filed by the Little Sisters of the Poor Home for the Aged, a religious nonprofit based out of Detroit. Despite already being exempted from the requirement to provide employees with contraception coverage, the Little Sisters have argued that signing the form for the exemption -- which would trigger a third-party administrator to provide and pay for the coverage the Little Sisters object to -- is itself a violation of their religious beliefs.

The second case was brought by Hobby Lobby, a private, for-profit craft company with stores throughout the country. In this case, lawyers for Hobby Lobby have argued -- with some success, so far -- that the contraception mandate violates the religious liberty of the corporation itself. The implications of the Hobby Lobby challenge -- for women's equal access to healthcare and for corporate personhood -- would be major.

If you think these cases only matter to women who use birth control, you're wrong. Here's why:

Contraception is basic healthcare, period.

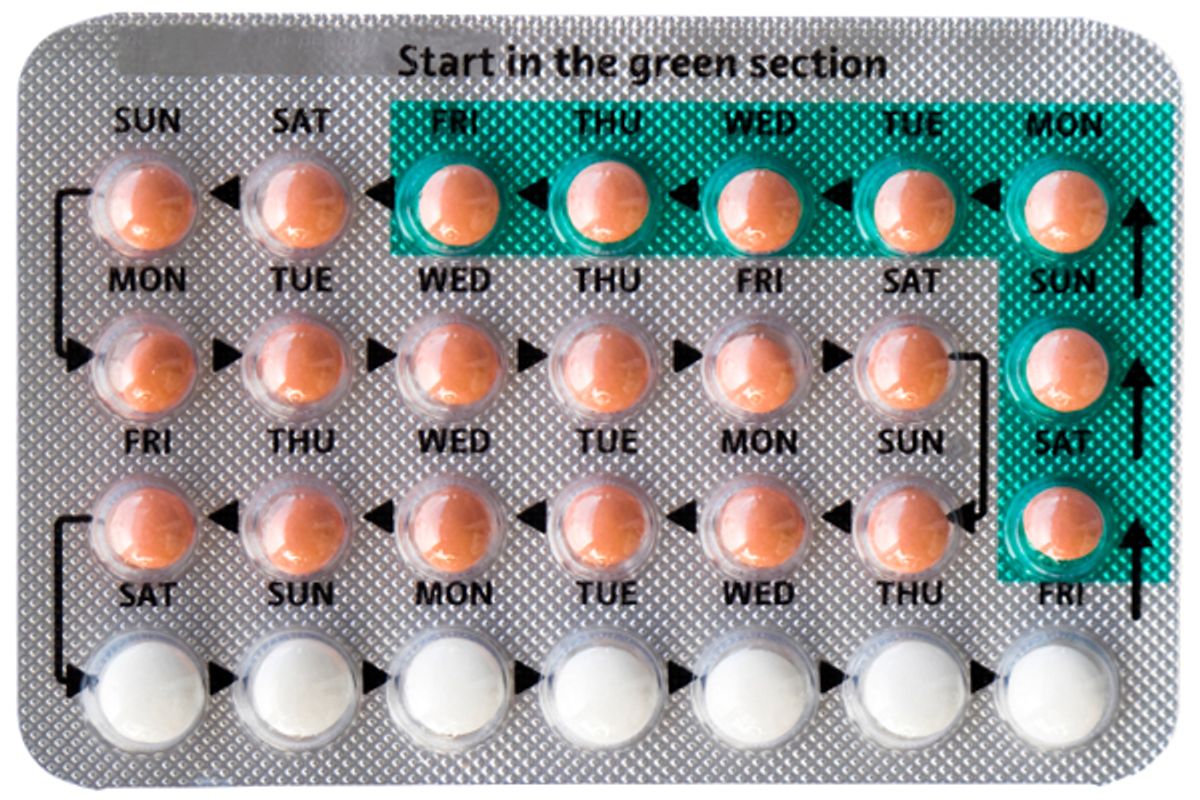

Contraception isn't a medical luxury, a "special" benefit or any of the other things that opponents of the insurance mandate have called it. Women take birth control for all kinds of reasons -- none of which are or should be anyone else's business.

So much of the rhetoric against guaranteed coverage of contraception is predicated on the assumption that preventing unwanted pregnancy is somehow unrelated to women's overall health, but this is just wrong. Controlling one's own fertility is a perfectly legitimate medical reason -- and the main reason -- that women use birth control. In the United States, 42 percent of women use oral contraceptives exclusively to prevent pregnancy, but a majority of women -- 58 percent -- use birth control for this reason and for reasons other than pregnancy prevention. Fourteen percent of women use the pill for purely non-contraceptive reasons, including preventing migraines, regulating periods and treating endometriosis.

None of these reasons are more valid or medically significant than the others, but they all make access to contraception important. The courts should recognize that allowing employers to decide what is "necessary" healthcare versus what is not is an incredibly dangerous precedent.

There is no such thing as "free" contraception.

As Jodi Jacobson at RH Reality Check recently noted, much of the coverage of the Affordable Care Act (even progressive coverage, including some of what I've written at Salon) says that it guarantees women "no-cost" or "free" birth control, but this is actually misleading.

If you have insurance, it's probably because you pay for it. Overwhelmingly, women either pay for it out of their own pockets on the private insurance market or through their compensation package, which is akin to wages. Any health services rendered through your insurance plan are paid for, in some form, by you. So birth control and other contraception are not "free" under the new mandate, a point Jacobson makes quite clearly:

No one can walk into any pharmacy today and get the pill without a prescription, which in any case first entails a visit to a doctor’s office. No one without insurance can walk into a doctor’s office and get an IUD for for free, nor any kind of contraception, unless they pay out of pocket or meet the means test for and are covered by Medicaid, an increasingly difficult enterprise in itself but the subject of a different article. Ten percent of women in the United States who work full time are currently uninsured and without coverage, they do not have access to “free” birth control. Nor do other women without insurance, or those whose plans are, for logistical reasons or because they were grand-fathered, not yet compliant with the ACA on preventive care. None of these women have “free” birth control now, and they will not later even if they get insurance.

Why? Because if you have insurance, you pay for it, either by virtue of your labor or out of your own pocket, or, depending on the situation, both. And under the ACA, it is now mandated that your insurance plan cover certain benefits without a co-pay. This does not make them “free.” It means that you are paying for that service as part of your premium. You earned it, you paid for it, it is yours. If you pay for it, you deserve to get it.

Allowing employers to refuse coverage means that women will have to pay extra for healthcare they are already paying for. You don't have to be a legal expert to realize that is unfair.

Contraception is essential to women's empowerment.

In addition to the personal benefit to women's lives, the social and economic benefits of greater access to contraception can't be overstated.

Contraception has long been financially out of reach for too many women. The Affordable Care Act is far from perfect, but it does represent the best chance millions of women will have at accessing necessary healthcare that will improve their lives.

As I have previously reported, a recent review of more than 66 studies conducted over three decades reveals that a woman’s ability to control her fertility impacts much more than just if and when she will have a child; contraception plays a significant role in shaping women's financial, professional and emotional lives, too.

According to Adam Sonfield, the lead author of the review from the Guttmacher Institute, "The scientific evidence strongly confirms what has long been obvious to women. Contraceptive use, and the ensuing ability to decide whether and when to have children, is linked to a host of benefits for themselves, the quality of their relationships, and the well-being of their children."

Major findings from the review reveal clear connections between access to contraception and college education and other degrees, career advancement, economic stability, healthier romantic relationships, mental health, general happiness, and children's health and well-being.

And when women do better, everyone else does, too.

Religious nonprofits have already been exempted from providing contraception to employees; what they are really fighting for is the "right" not to sign a piece of paper.

The Obama administration already granted religious nonprofits an exemption from the law if they object to contraception for religious reasons. All these organizations have to do is fill out a form stating that they want an exemption, and a third-party administrator will provide contraception coverage for them. The organizations do not pay for the contraceptive coverage, the third-party administrator does. Signing a form to receive an exemption from a healthcare law is very easy. Signing a form is not a violation of religious freedom. It is signing a form.

But, as Amanda Marcotte at Slate pointed out this week, these organizations want an exemption from the exemption: "These groups are arguing that filling out a form is a violation of their religious freedom and that 'religious freedom' means that you should have control over your employee's health care decisions even when they happen outside of the insurance coverage you directly provide for them."

The Little Sister's complaint is akin to telling their employees where they can spend their wages when they leave work at the end of the day. No employer should have that kind of power to control workers' lives.

(What makes the Little Sisters' claims particularly absurd is the fact that the organization uses a so-called self-insured "church plan" that wouldn't have been compelled to provide contraceptive coverage in the first place. The nuns' employees were always going to get cheated out of a comprehensive health plan, anyway.)

If employers are empowered to control women's healthcare, it won't end there.

The fundamental issue at stake in these cases is to what extent employers are empowered to treat women as second-class employees. But the outcome of these cases will have broad ramifications in terms of what kind of control religiously affiliated employers -- and private for-profit companies with executives that hold particular religious beliefs -- have over all employees.

Some have called the Hobby Lobby case a Citizens United redux, a legal test on the limits, once again, of corporate personhood. At issue this time is the bizarre question: Can corporations hold religious beliefs?

The sane person's answer to this question is "no," but the Supreme Court has yet to decide whether a for-profit corporation -- that incorporated to specifically protect itself from personal liability -- is legally entitled to the same kind of religious freedom exercised by individual people. Perhaps, then, the bigger question is: Can corporations have it both ways? Can a private company have all of the freedom from liability that incorporation provides, and a select menu of personal liberties when such liberties are deemed advantageous?

The 10th Circuit says yes; the 3rd Circuit argues no. But it's what the Supreme Court thinks that will really matter. For women, yes, but also for everyone else who doesn't want to have their employer's religious views determine how they live their private lives.

Shares