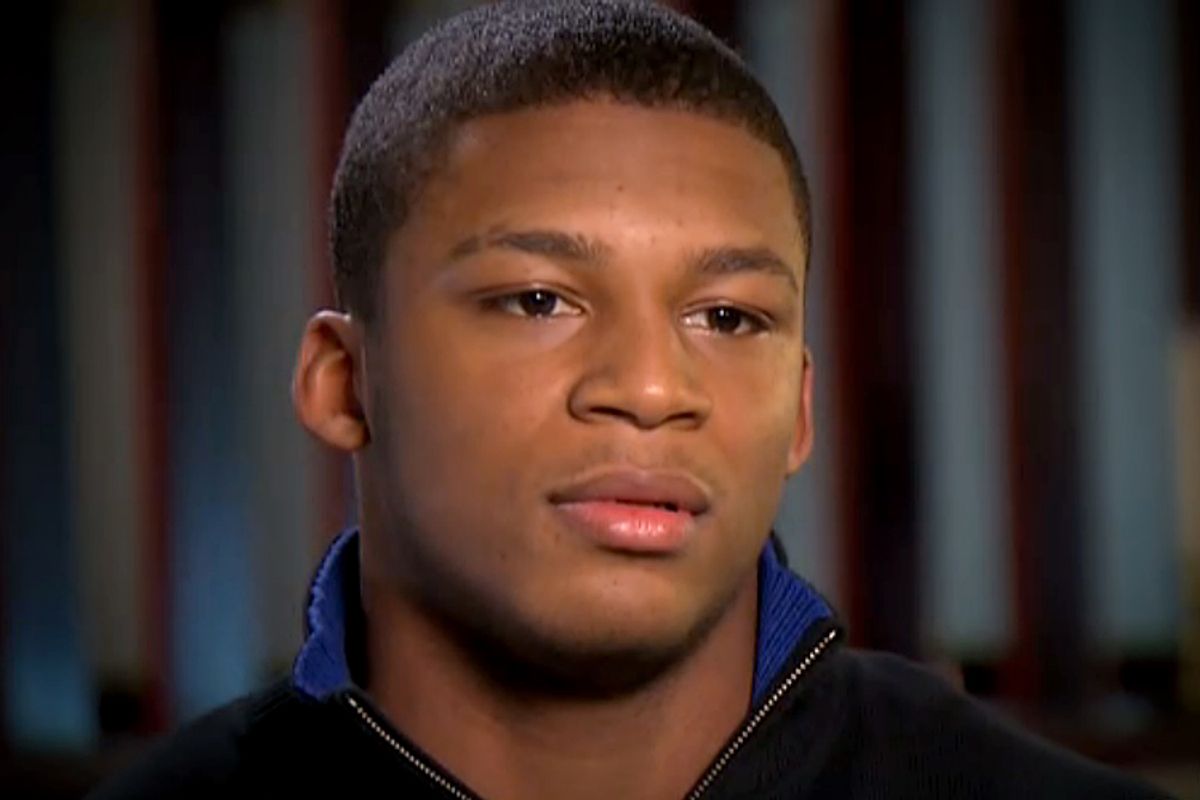

Ma'lik Richmond, one of the two teens convicted last year of raping an unconscious 16-year-old girl in Steubenville, Ohio, was released from a juvenile detention facility this weekend. Richmond's release comes three months earlier than his recommended minimum sentence of one year, but that isn't all that surprising, really. Because of his age and status as a first-time offender, his sentence was likely contingent on his behavior and the "rehabilitative process." Juvenile detention -- at least nominally -- is supposed to be aimed at helping young people grow and develop so that they can get on with their lives. Longer sentences don't automatically mean more justice, and getting out early isn't necessarily a bad thing.

But what is troubling about Richmond's release has everything to do with the statement issued by his lawyer to announce the news. "The past sixteen months have been extremely challenging for Ma'lik and his extended family," said attorney Walter Madison on behalf of his client. "At sixteen years old, Ma'lik and his family endured hardness beyond imagination for any adult yet alone child. He has persevered the hardness and made the most of yet another unfortunate set of circumstances in his life."

You can read the full statement here, but it continues on in this blithe manner -- with no reference to remorse for the rape Richmond committed, let alone an acknowledgement of the victim whose life was upended by the sexual assault and humiliation she experienced at the hands of Richmond and Trent Mays on that August night in 2012.

In other words, it is a classic non-apology. A signal right out of the gate that the narrative for the Richmond camp hasn't changed over the last nine months. He is still a victim who had to "persevere" through the "ordeal" of taking responsibility for a crime he committed. The person who thought that a young girl who could barely hold her head up to speak was "coming on to me," and that carrying her seemingly lifeless body around like luggage was "just clowning around." Judging from the statement, which was no doubt thought through by Richmond's lawyer before being released to the public, the lesson Richmond learned in detention wasn't about personal accountability, a culture of male sexual entitlement or the harm he caused his victim and her community -- it was that he was victimized by the public and the justice system.

Bob Fitzsimmons, the lawyer for Richmond's victim, openly criticized the statement for failing to "make a single reference to the victim and her family -- whom he and his co-defendant scarred for life. ... Rape is about victims, not defendants. Obviously, the people writing his press release have yet to learn this important lesson."

Of course, any statement from Richmond's legal team is going to emphasize his perspective and present him in a positive light, but it's possible to do this in a way that acknowledges that his actions had consequences. That he victimized and sexually exploited another person, and that he is sorry for that. This kind of language of personal responsibility -- if Richmond really was educated and reformed during his time in detention (and if his legal team allowed that education and reform to come through) -- should come naturally.

Rehabilitation can and should be a priority in the criminal justice system over reflexive incarceration -- for all people, but certainly young people. And a system of rehabilitative justice is particularly effective in younger populations, as Irin Carmon has previously reported for Salon. Consensus in the juvenile justice and medical communities holds that young people should be given counseling, not hard time, for crimes they commit:

Rehabilitation, of course, is one of only three separate functions that intervening in sexual offenses serves, explains Mark Chaffin, professor of pediatrics at the University of Oklahoma College of Medicine and director of research at the Center on Child Abuse and Neglect. There is “community protection,” identifying predators and keeping those who might re-offend away from potential victims. There is “accountability,” which sends a message as to what is and isn’t acceptable in a community. And then there is rehabilitation, on which researchers are quite optimistic -- at least when it comes to juveniles.

“Twenty years ago people lumped juveniles and adults together, and had this idea that if a kid committed a sex offense, he was on this immovable trajectory that was going to head towards more and more sexual deviancy and a lifetime of predation,” says [Elizabeth Letourneau, associate professor at the Bloomberg School of Health at Johns Hopkins and the director of the Moore Center for the Prevention of Child Sexual Abuse]. “But that just isn’t the case.”

It's early still. Perhaps Richmond will come out and address -- directly and without evasion -- the harm he caused his victim, his resolve to continue to learn from the experience and help others do the same. But the first statement on his behalf is a disheartening indication that we can likely expect more of the same denials and passing of blame. And that is in part the fault of the juvenile justice system, not just young people like Richmond who go through it.

If Richmond ended his time in juvenile detention without a sincere understanding of his actions and the conditions under which sexual violence is condoned and repeated in our culture, then justice has truly failed -- not only his victim, but Richmond himself.

Shares