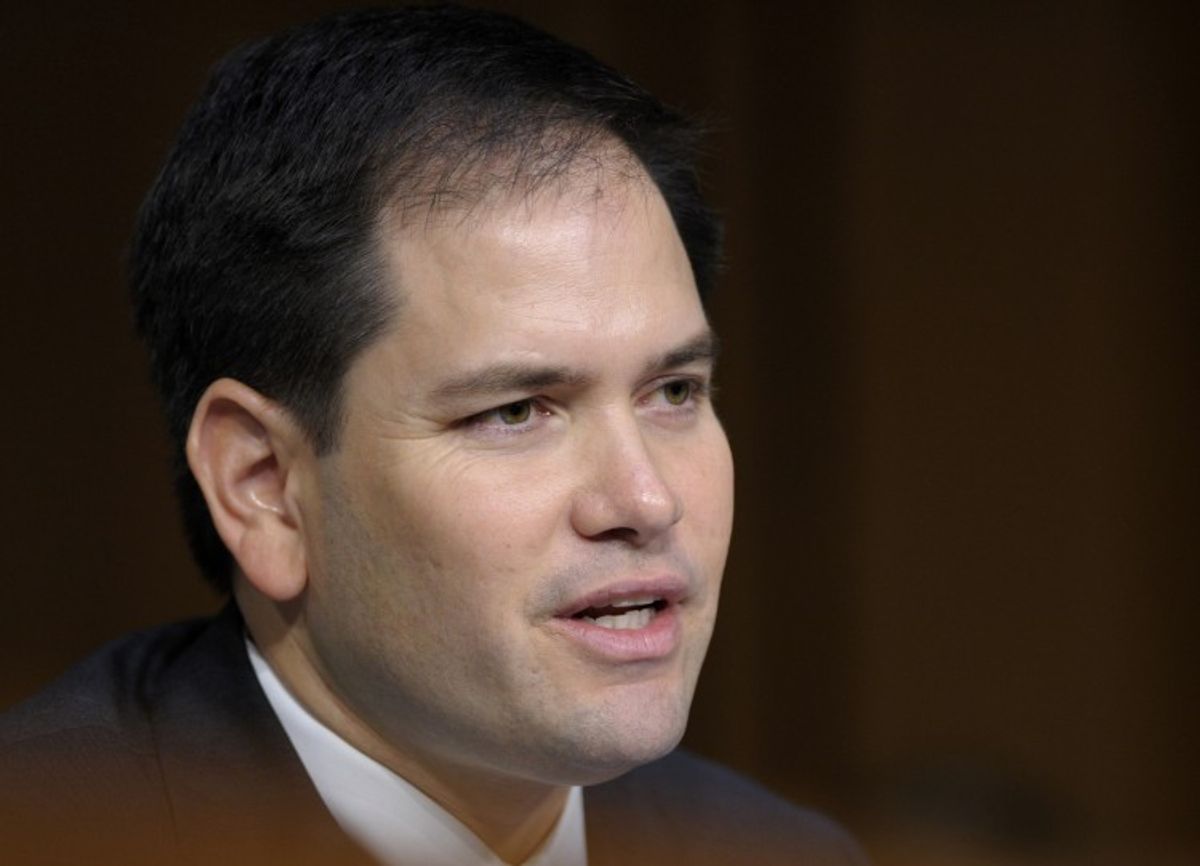

Truth be told, 2013 was not a good year for Florida Sen. Marco Rubio.

His great achievement — helping to shepherd a comprehensive immigration reform bill through the Senate — proved pyrrhic. It immediately died in the House (though rumors of a piecemeal revivification abound) and its passage in the Senate thoroughly pissed off a conservative base that, in the grip of a profound racial panic, is obsessed with dreaded “amnesty.”

The blowback was so fierce that Rubio spent much of the remainder of the year artlessly veering to the far right, hoping to salvage his right-wing bona fides through a series of symbolic votes that did little more than make the likely presidential aspirant look like “a walking press release announcing a no vote,” as Jim Newell memorably put it.

The whole thing was kind of sad, really, and watching it evoked a feeling not unlike that brought on by reading the final pages of “1984.” By the time he was voting to prolong the government shutdown, breach the debt ceiling, and deny millions much-needed unemployment insurance, it was fair to say that Rubio had “won the victory over himself.” He loved Big Brother.

No surprise, then, to see the once-and-future 2016 contender kick off the new year with yet another rebranding campaign, this one seemingly intended to mend fences with an establishment that had watched his earlier pandering with growing chagrin. Forget comprehensive immigration reform; in 2014, Marco Rubio has a new noble crusade on his mind. He’s fighting a war on poverty.

But despite my strong desire to be a fair-minded, discerning and nonpartisan individual — a liberal, in the best sense of the word — I must confess that my reaction to Rubio’s big speech on poverty has been far less sanguine than that of the New Republic’s Jonathan Cohn. Like Salon’s Alex Pareene, I’m skeptical.

“Rubio engaged in a conversation Republicans have shunned for too long,” wrote Cohn. “That's progress.” But I think Pareene was closer to the mark when he wrote that, for GOPers, feigning concern for the indigent is “one way to help shake the correct impression voters have that Republicans are devoted solely to the further enrichment of the already wealthy.” I’m a glass half-empty kind of guy, I suppose.

In Cohn’s defense, he acknowledges that just because Rubio has put forward some policy ideas, “[t]hat doesn’t mean they were good proposals.” Indeed, from what Rubio has outlined thus far — his speech was, understandably, sketchy on the details — the senator’s ideas for helping the poor are seriously problematic. And what are those ideas? 1) To replace the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) with a wage subsidy; and 2) to transform all of the federal government’s existing anti-poverty programs into a big fund that D.C. would hand over to the states to handle on their own.

Now, while there’s definitely a good argument to be made in favor of wage subsidies, Rubio’s decision to scrap the EITC in their favor is somewhat perplexing. True, the EITC isn’t perfect; it’s very effective for those with families while being considerably less supportive for childless adults. But that’s an argument for expanding the EITC for childless adults — or adding wage subsidies in addition to the EITC — not scrapping the program entirely.

What’s more, according to Cohn, Rubio’s wage subsidy plan is “budget neutral,” which means that he would expand the number of people receiving government assistance without increasing the overall amount of spending devoted to that purpose. The program would serve more people, but the funding would stay the same. The almost certain net result? An increase in child poverty.

Even more troubling is Rubio’s plan to turn the welfare state into a big fund of money to be doled out to the states in block grants. Unlike the wage subsidy proposal, this is an idea with a long lineage in Republican politics (a clear warning sign if there ever was one). I understand the appeal to Rubio, certainly. For reasons principled and not, federalism remains a popular shibboleth on the right. And regular Americans like the sound of anything that makes “Washington” less of a presence in their lives.

But as Sharon Parrott of the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities notes in a recent blog post, block granting is deeply flawed, both structurally and politically. On the structural level, block grants are simply far less responsive to the ups and downs of the economy than are simple entitlement programs. It's easier for the federal government to spend more during times of strife than it is for states. Moreover, despite Rubio’s implications to the contrary, D.C.’s existing anti-poverty programs already adjust for each region’s varying levels of economic strife, population, job availability and so forth. They are not “one-size-fits-all” programs, despite Republican insistence to the contrary.

The other major problem with block granting is that the politics of cutting a block grant are far less thorny than they are for cutting a defined entitlement. In other words, while it’s easy for Congress to cut, say, 5 percent from a block grant without outlining where these cuts will actually fall (delegating that unpleasant business instead to state legislatures), it’s considerably harder to target a specific entitlement, and the people it serves, for the chopping block.

There’s a larger, philosophical problem with Rubio’s kind of federalism, though, and it’s one that’s all too easily seen in America’s recent history. As the Daily Beast’s Jamelle Bouie notes, one need not engage in wild fantasy in order to envision the consequence of giving so much authority to the states. Just look at Medicaid, a program that gives the states great discretion for establishing standards of their own, and you’ll find that benefits are far more generous in blue states than in red. If we as a people decide that an underprivileged American deserves adequate healthcare, then it shouldn’t matter whether she happens to live in Brooklyn or Boise.

So Rubio’s plans, such as they are, leave a lot to be desired. Yet I’m hesitant to give him a failing grade, especially when I keep in mind that even these tenuous and meager steps have been greeted by the dumber members of the far right with harrumphing disapproval. I’m hoping Rubio ignores these dead-enders and continues to engage with those sincerely interested in alleviating poverty. But if his retreat on immigration reform last year is anything to go by, I won’t be holding my breath.

Shares