A friend of a friend of mine has big plans: quit his prestigious editorial job in New York, grow his beard a bit further out, and start working on the docks. In 2014, the sentiments behind such a decision aren't anything new, but they're becoming more and more visible in our pop culture. You know the litany already: Gender roles in the workplace and the family are blurring, outsourcing is closing factory after factory, once-secure manufacturing jobs are disappearing. “American men don't know how to make things anymore,” and all that. For a certain slice of American men, a romance has cropped up around working the docks, or an oil rig, or a crab boat up around Alaska. You're getting back in touch with something, some supposedly inherent masculine energy that seems ever more ineffable as the nation adjusts its identity for a new era.

Last year saw a handful of filmmakers take on the questions of what it means to be a man in America in the 21st century, but their films don't celebrate archetypal images of frontier manliness. Rather, they seem to suggest that looking back to these old forms is another broken urge in an age of cultural nostalgia.

After a decade of male antihero-dominated prestige TV dramas, the problem of contemporary American masculinity had its thematic apotheosis with “Breaking Bad.” Walt might have gotten a bleak version of a final Wild West showdown, but one of the most lasting images of the final season was that of him wasting away alone in a frozen cabin in New Hampshire. All the bluster of Heisenberg faded as Walt was corroded by the consequences of his actions -- we saw up close the perversity of a man like him living alone in the woods. But while “Breaking Bad” did condemn old archetypes of masculinity to a degree, other stories seem to eulogize them as they slip away. Such an impulse toward eulogy has run through a handful of recent movies, most notably Jeff Nichols' “Mud,” Derek Cianfrance's “The Place Beyond the Pines” and Scott Cooper's “Out of the Furnace.”

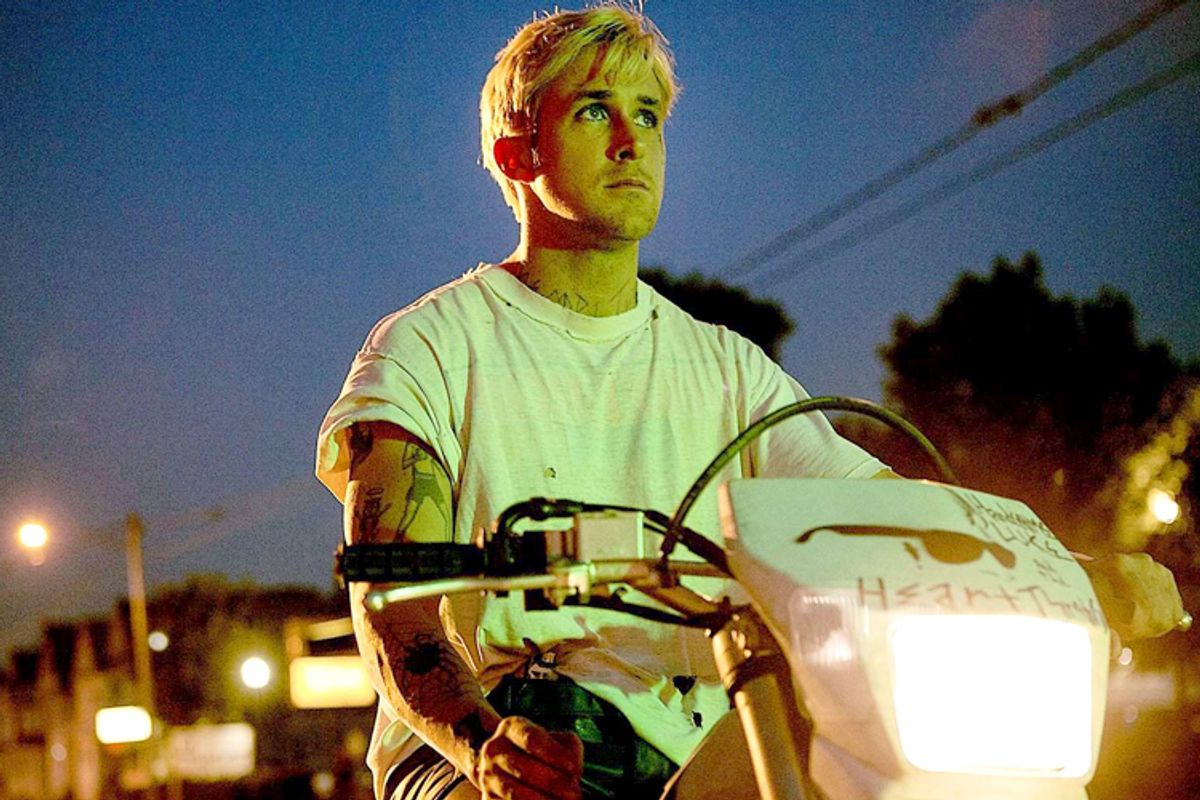

Though they may initially seem to have little in common, the settings of each film all present classic figments of Americana as if they are synonymous with the raw nature of our country's landscape, a landscape in which listless male characters see their conceptions of life fragmenting. Each movie is shot in its own way, but each poeticizes decrepitude. The moss-covered porches and shuttered storefronts of Braddock, Pa., in “Out of the Furnace” aren't so different from the strip malls and Piggly Wiggly in “Mud.” Luke and Romina, the ill-fated lovers of “The Place Beyond the Pines,” work as a traveling circus performer and a waitress. There's something inescapably Springsteen-esque about their struggles, emphasized by the moment where “Dancing in the Dark” fades out as Luke walks up to the diner where Romina works.

That strain of down-on-your-luck American iconography runs through “Out of the Furnace,” as well. When Russell is released from jail, the very next scene begins with a shot of the road leading to the steel mill. Like much of “Out of the Furnace,” the symbolism isn't overly subtle: a prison lies at one end of the road, the mill at the other. That mill appears as a darkened structure nearly indistinguishable from the earth it sits upon, either as barbaric as nature or being reclaimed by nature. Everything in Braddock is in the process of becoming a ghost.

Cooper, Cianfrance and Nichols also turn to immortal tropes of the past to address a much more contemporary preoccupation with a fading sense of rugged American masculinity. The most overt of these is the biblical influence on “Mud.” The isolated island where Mud lives is Edenic; it's unclear for much of the movie whether Mud himself is supposed to be the snake in the garden or the First Man. It's the battleground upon which Ellis' loss of innocence takes place, the boy's disillusionment boiling over into a confrontation with Mud that shatters the adventurous, paradisal escapism of the island.

Of course, linking biblical or classical ideas to American mythology is far from new. The difference here is that with each movie's more or less contemporary setting (“The Place Beyond the Pines” begins in the '90s, but ends in current day), it feels as if the traditional imagery — both American, and further back — is being deployed as a last-ditch attempt at inflating characters who have stopped making sense. These are broken archetypes wandering through archetypically desolate landscapes. They are men of the frontier, but also victims to it.

In each film, some character embodies a mythic vision of American masculinity. These characters are almost always shown either as out of step with the world around them, or as reflecting ways of life that are dying. They never triumph in an uncomplicated way. Just as the plots of these movies nod to biblical motifs, the characters themselves often take elements of stock fictional depictions of rugged masculinity. Mud is an island man as Rodney (or, on the darker side, Harlan) is a mountain man, as Luke is classical outlaw, a bank robber.

Of all of these, it's Mud who's most romanticized. He first appears as something of an apparition, the boys noticing cross-marks in the sand from his boots. They turn around and he's standing by the tide — appearing out of nowhere, out of nature. He presents himself as an American mystic living out in the swamp, but also sounds like a rambling Beat. The crosses are nails meant to “ward off evil spirits.” As Ellis talks to both Mud and Tom Blankenship, the men mythologize one another. According to Mud, Tom is an ex-CIA assassin living a quiet, monkish second life in a houseboat; Tom claims Mud was “living in the woods when I first met him.” It's unclear whether anything the men say about each other is actually true, but all of it paints Mud as a romantic outlaw.

In “The Place Beyond the Pines,” Jason hears that his father, Luke, is an “outlaw,” but the tone of the word is far different than when it's applied to Mud. In “Mud,” there's the creep of disenchantment — the fact that, far from a man bending the earth to his needs, Mud is a man on the run from the law, relying on Ellis' groceries for sustenance. Luke, meanwhile, is a tragic outlaw. What would be mythic in a film less concerned with consequence gets refigured as something shameful. Luke thinks he's living in a Wild West fantasy, but winds up slain by a cop and leaving his son without his biological father. Such complications are what bring each film's ideas into the modern day. We're shown all sorts of classic imagery of frontier masculinity, but we're rarely led to believe the writers, actors or directors behind these characters consider them feasible in a contemporary setting.

What hangs over all of this is a tension between classic visions of manhood and a landscape that's begun to move beyond them altogether. “Out of the Furnace” makes it explicit, and occasionally too obvious. Russell's mill work and a hunting sequence are juxtaposed against Rodney's refusal of a steady job in favor of fighting for money. In their way, both characters represent traditional masculinity through the physicality of their work. But Rodney's status as an Iraq War veteran makes him, in one way, of the modern world. Russell's factory life is a remnant of a dying lifestyle, where Rodney's reclamation of a more visceral sense of masculinity could be seen as an extreme counterpoint to the emasculation Russell experiences through looming unemployment and his girlfriend leaving him for another man during his time in jail. “Out of the Furnace” doesn't buy into that, though; Rodney's brashness eventually gets him killed. The failures of the characters in “Out of the Furnace” are similar to Luke's failures in “The Place Beyond the Pines,” all the men deal with the consequences of trying to embody an inherited vision of masculinity. Even Mud becomes — to gesture toward the Beat language he himself echoes — a holy fool, chasing after the icon of Juniper he's built up in his head rather than realizing the truths about their relationship.

It's worth returning to that hunting sequence in "Out of the Furnace." Placed against Rodney's fight in the Ramapo Mountains, together the scenes illustrate ritual displays of male control — over nature, over beasts, over themselves. The men of these movies are inevitably tied to the American landscape. They are born from it, but in their failings, they are also overcome by it. Each film centers on an interplay between these characters and their environment, between the marks of humanity and nature.

This comes out most clearly in the ways each film presents machinery and man-made items lost in nature. In “The Place Beyond the Pines,” Luke almost seems a creature of the countryside. His circus rolls through town based on the cycle of seasons; we see him riding his motorcycle rapidly through the woods as if he knows the land. True to the movie's title, however, it's out in nature that Luke and Avery come to terms with the more animalistic or darker corners of themselves. Luke goes into the woods and emerges a bank robber; Avery is made to face the physical result of his killing Luke. Natural settings here, as in “Mud” and “Out of the Furnace,” are where men are forced to reckon with themselves and face the futility of the structures they've built up, both figurative and literal. It's there in the beginning of “Mud” in the image of the boat stuck up in the tree and littered with fallen leaves. Even though that boat's running by the end of the movie, it's dragging along the dark shadow of the violent gunfight that erupted at the film's climax. As for “Out of the Furnace,” the steel mill that looms over Braddock and the film alike is on its way to becoming a shell. In the climax of the film, Russell chases Harlan among its ruined corners, through collapsing walls and rails overgrown with brush. The frontier that a character like Russell seems born out of is in the process of reclaiming the man-made symbol of what Russell is.

Even as each of these films undercuts the classic imagery it uses, none of them end without one last gesture toward dominance or transcendence. Both “Mud” and “The Place Beyond the Pines” end with a play on the classic trope of riding off into the sunset. Mud and Tom sail the boat out into open water. Jason purchases a motorcycle, inheriting more strands of his father, and rides off down roads winding through the mountainsides. Neither of these endings are clean or peaceful, and the characters in both still carry the baggage of the events that lead them to this final point. “Out of the Furnace” is more conflicted still — Russell avenges Rodney by shooting Harlan, and then there is a final shot of him sitting alone in his house, with no escape or reprieve after his actions. If these are final touches of romanticism, they are self-conscious ones.

For a moment, it may seem as if each of these films wants to uphold the mythic outlaw figures they've messily deconstructed along the way. As ambitious as these films are, none of them seem entirely sure what their endings should mean. And that makes complete sense. These are movies dealing with a concept and a trend as it unfolds. We don't know where it's going or what should replace it. Longing and wearied, “Mud” and “Out of the Furnace” and “The Place Beyond the Pines” are all stories by men about the sorts of men they might want to be, but with the knowledge that the world is leaving those sorts of men behind.

Shares